Eager nurses dive into public-health system’s inviting travel float pool

Benefits, pay, flexibility draw nurses who migrated to private agencies

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/07/2024 (507 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The provincial government has hired 175 nurses for its travel nurse float pool targeted at reducing the public system’s costly reliance on staffing from private agencies.

Shared Health executive director of health services Nicole Sneath said roughly 70 per cent of the total hires had worked shifts for private nursing agencies before they joined the provincial pool.

“We’ve grown really quickly, and it’s been great to hear the feedback from the nurses,” Sneath said. “So that as we continue to evolve and develop our processes… we can make sure we’re supporting the nurses and we’re also meeting the needs at the (health-care) site.”

As of earlier this month, the float pool is made up of 159 casuals, 15 full-time nurses and one part-timer.

Nurses aren’t permitted to work for a private agency and be in the float pool at the same time in areas where it operates.

The pool, created under the previous Progressive Conservative government in 2022, operates in every provincial health region except Winnipeg. Discussions are underway to expand it to the city in the fall.

The Manitoba Nurses Union came up with the idea for the pool during its last round of labour negotiations.

There have been bumps along the road — an unexpected number of applications earlier this year resulted in long waits to join the pool. MNU president Darlene Jackson said there were as many as 300 applicants waiting for interviews at one point.

The pool has been positioned as a solution to the public health system’s reliance on private agencies and record-high spending on nurse travel.

Participating in the pool allows nurses to bank pensionable hours, keep their provincial benefits and maintain seniority, which are key advantages for people used to the higher pay and schedule flexibility provided by agencies where the tradeoff is the absence of benefits and union representation.

The pay rate is “comparable” to what they’d earn in a hospital position, Sneath said. But the pool premiums can be more lucrative, particularly for work in the North.

On top of those premiums — which can work out to 25 per cent of their current wage, in some cases — nurses’ expenses are paid and they can choose where and when they work.

Some interested nurses who waited months for their applications to crawl through the backlog picked up agency shifts in the meantime.

Two nurses who spoke on the condition of anonymity waited months to get into the pool.

“It’s a pretty good setup that they’ve arranged… but the only problem is, I think when they initiated it, the administrative (side) wasn’t supported well enough,” one said.

“So they’ve been completely overwhelmed with the number of people who have interest and want to get started. Even just to get interviews, it’s been taking some people months.”

She continued private-agency work while waiting.

“It was just such a long process to be able to start even looking at how to pick up shifts. But I feel like with the way we’re constantly talking about lowering (use of) agency nurses… it should have been rolled out with a simple, streamlined process.”

Another nurse said it took three months for Shared Health to offer her a pool position after she was interviewed earlier this year.

“They were very helpful when they got back to me, but they’re clearly overwhelmed,” she said.

Sneath said two managers conduct interviews and oversee the pool’s operations, but the team will be expanded. The average post-interview wait time was a few weeks and it’s down to a few days, she said.

“It’s a good problem to have, in that, because of the interest, there’s been times where we’ve had kind of a surge in applications… so there might be a little bit of a delay,” she said. “It’s been an evolving, growing program, and so we’ve worked really hard to look at all of our processes and make them as efficient as we can.”

The applicants typically have full-time or casual jobs at hospitals or other health facilities, and pick up travel shifts on the side.

About 30 facilities currently fill shifts with pool staff. A list of health centres that need travel nurses is posted online.

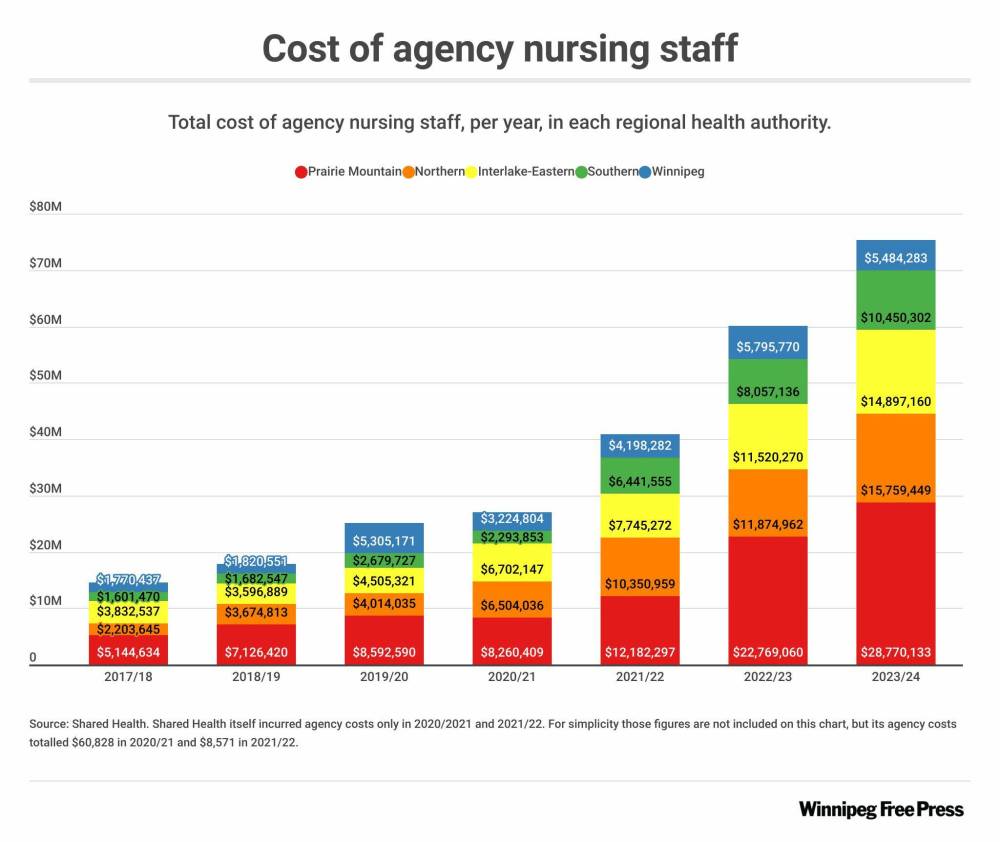

Preliminary figures provided by Shared Health show the province spent a record $75.3 million on private nurse agencies in the 2023-24 fiscal year. The highest spending by region, at $28.7 million, was in southwestern Manitoba’s Prairie Mountain Health region.

“It is so much higher than what normally would be spent on nurses in the public system,” Jackson said. “So we want to put those dollars back into our public health-care system. That means that we have to decrease our use of agency nurses.”

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS FILES Manitoba Nurses Union president Darlene Jackson said there were as many as 300 applicants waiting for interviews to join the travel nurse float pool. She is hopeful the growing pool will reduce Manitoba’s use of private agency nurses.

Health regions that filled shifts with float pool nurses paid approximately $3.19 million to Shared Health this fiscal year. That figure doesn’t reflect the pool’s latest expansion efforts, a Shared Health spokesperson said.

Shared Health absorbs the administrative cost of the program and pays nurses directly for worked shifts, later recouping the costs from regional health authorities that use funds allocated for nurse staffing.

The program isn’t just about the money, Sneath said, noting pool nurses get orientation, education and mentorship private agencies don’t provide.

“The pay is one aspect, but all the other things are really important,” she said, saying feedback from nurses helped inform the pool’s orientation process.

The goal is to ensure nurses picking up shifts are familiar with the policies and practices of each regional authority and the facilities within. That is not always a given with agency nurses, Jackson said.

“It can only be good for patients when nurses that come into work are oriented and they understand the facility, they understand the type of clients they’ll be working with,” she said.

“It can only be good for patients when we have that type of standards placed on travel nurses.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.