Waiting to exhale

The advent of iron lungs gave polio victims a chance to live in the decades before a vaccine emerged, but the technology put incredible demands on nurses

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/02/2021 (1786 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Between 1928 and 1953, Manitoba experienced six large polio epidemics. In that time period, many people with polio were hospitalized at the King George Hospital.

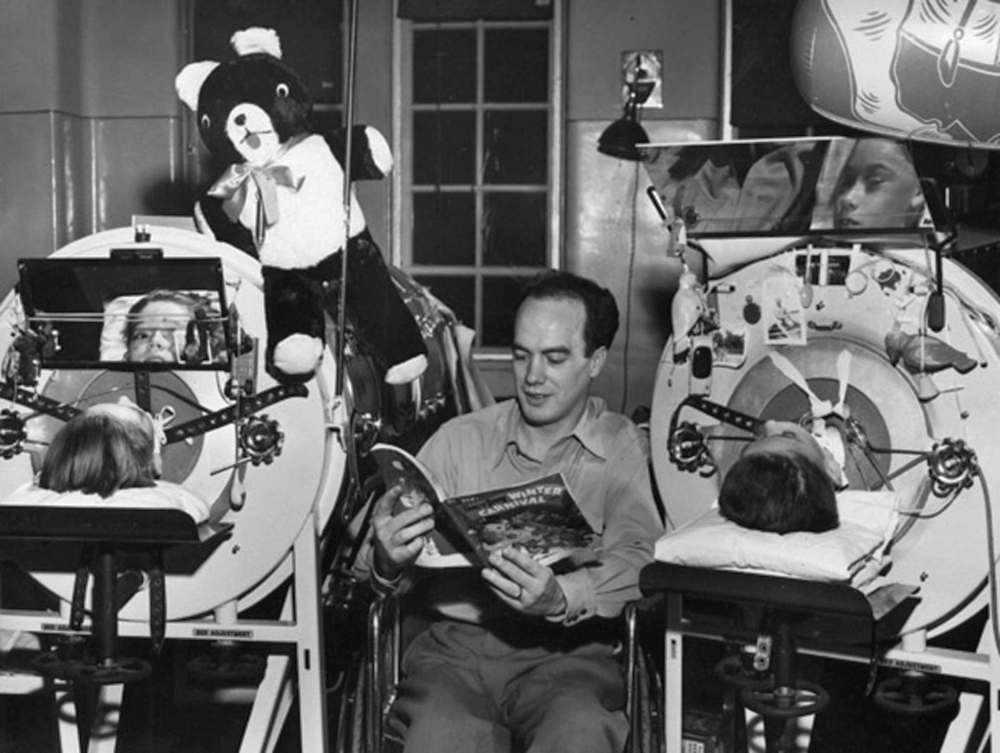

The King George, the King Edward, and Princess Elizabeth Hospitals together formed the Winnipeg Municipal Hospitals, located where Riverview Health Centre now stands. Riverview’s small on-site museum has a number of interesting artifacts. The biggest one, in terms of size and cultural impact, is the respirator — popularly referred to as an iron lung.

Big, bulky, and kind of ominous, the respirator is likely the most well-known symbol associated with polio. Respirators highlight ethical questions about treatment, the changing nature of nurses’ work, and they can show us how Winnipeggers faced epidemic polio together.

In the summer of 1953, Manitoba was in the midst of a polio epidemic of historic proportions. More than 2,300 cases were reported by November of that year. The case rate of 286.4 per 100,000 population makes it the largest polio outbreak per capita in Canadian history.

Manitobans were very familiar with polio by that year. Prior epidemics in 1928, 1936, 1941, 1947 and 1952 made sure of that. Vaccines made polio practically negligible by the 1960s, but for decades Manitobans lived with the physical, social and emotional effects of the disease.

The communicable disease is caused by the poliovirus. It can enter the body’s digestive system due to improper hygiene and sanitation techniques. The poliovirus is usually killed in the gastrointestinal tract. If not, it can attack the central nervous system, resulting in paralysis, usually of the limbs, shoulders or abdomen. It can also attack the parts of the central nervous system that control swallowing and respiration. This type, called pharyngeal or bulbar polio, was almost always fatal until the widespread use of respirators.

Polio frightened people in the early years because it caused paralysis and it mainly affected children under the age of 10. With each successive epidemic, the age of patients increased. So, too, did incidences of bulbar polio.

Despite the recurring epidemics, people did not become complacent, something that can be seen in the many attempts to find treatments, cures, vaccines — anything to lessen the effects. Some, such as nasal sprays that turned people’s noses yellow, were not helpful. Others, including respirators, made a huge impact.

The introduction of respirators to Manitoba during the 1936 epidemic raised complicated ethical questions. The Municipal Hospitals had only one respirator. Dr. A.B. Alexander, the medical superintendent there, worried about potentially having multiple patients who needed a respirator, placing doctors in the unenviable position of deciding who might live or die. Alexander hoped the province would buy more respirators so no one would have to make that decision.

Manitoba obtained more respirators, but there were never enough. During the 1953 epidemic, Manitoba borrowed some from other jurisdictions. Health officials purchased more respirators as cases continued to mount. The Royal Canadian Air Force made at least one mercy trip to Boston to pick up machines straight from the manufacturer.

Respirators work on the principle of negative pressure. They have bellows, which are motorized blowers. When the bellows contract, air pressure in the respirator decreases. This expands the chest, and lets air in to the lungs. Unlike the ventilators used for COVID-19 patients, respirators were safe for long periods of time because they did not mechanically compress the chest, nor did they use pumping devices to inflate the lungs. Some people only needed to them for a short time. Others needed respiratory assistance for years, or permanently.

The widespread use of respirators changed the way nurses cared for patients. Prior to their introduction, most people suffering from bulbar polio died quickly. For those whose limbs were affected, the standard treatment before the mid-1940s was rest and immobilization. This was done by splinting the limbs. Respirators made polio nursing more labour intensive and technologically driven.

Nurses worked with doctors to provide the best possible care to people in respirators. Nurses needed to understand not only the principle of negative pressure, but how to set the proper rate and depth of respiration for each individual patient. This was done using a number of knobs and dials on the machine. It was indicated by a gauge which had to be monitored constantly. Nurses were responsible for monitoring and adjusting the gauges and readings on each individual respirator while also attending to the patients’ other medical issues.

Early respirators had to be opened in order for nurses to care for patients. By the 1940s and ’50s they had air-tight portholes through which nurses could place their hands. This meant patients could be cared for while in a working respirator, but it made the nurses’ work more difficult. They had to change sheets and bedpans without seeing what they were doing. Working with respirator patients mean nurses had to widen their skill sets, which they did successfully.

As respirators became commonplace, power outages became a constant source of anxiety. Respirators could be operated by hand in the case of a power outage, and manufacturers made it sound easy. Nurses who were trained to operate them manually knew this was not an easy task. It was a physically and emotionally demanding job. Nurses knew that in the case of a blackout, they would be responsible for keeping people in respirators alive.

A power outage was one of the biggest fears for anyone working on a polio ward. At the height of the 1953 polio epidemic, when 92 people were in respirators at the King George Isolation Hospital, the power went out for four hours.

It took three people to keep each machine running. One person operated the bellows, another monitored the pressure gauges to make sure the first person was using enough pressure. The third person watched the patient’s face and hand to prevent cyanosis (lack of oxygen), kept tracheotomies clear, and likely kept the patients calm.

But the King George did not have enough staff for that. When they heard the polio wards had lost power, the staff from the other Municipal Hospitals rushed over to help. That still wasn’t enough. Luckily, many people from the surrounding neighbourhood rushed to the King George to help in any way they could, even if it meant simply holding a flashlight. For four hours, medical personnel and concerned neighbours worked together to keep the 92 people in the respirators alive.

Representative of mid-20th century technology, respirators are big, bulky and loud. Respirators gave people with a usually fatal case of polio a chance to live, but they also created ethical dilemmas for physicians and led to an increasingly complex relationship between technology and care for nurses. Yet, they also helped strengthen community bonds between patients, neighbours and medical personnel in the midst of an epidemic.

This article was written by Leah Morton, PhD, for the Manitoba Historical Society. Leah is the curatorial assistant at the Manitoba Museum. She has authored numerous articles and essays of historical significance pertaining to the health and welfare of all Manitobans.