Brian really was lyin’

Memos prove Mulroney was totally involved in CF-18 debacle

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/08/2010 (5671 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

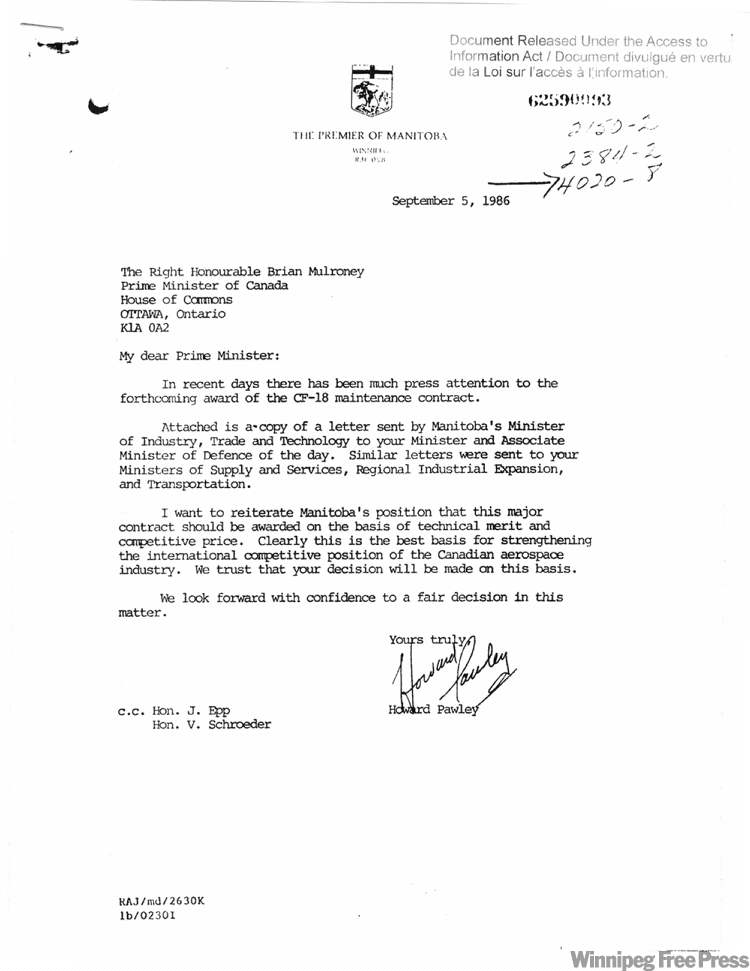

OTTAWA — Twenty-four years ago, former Manitoba Premier Howard Pawley accused Prime Minister Brian Mulroney of lying to him outright about a 20-year maintenance contract for CF-18 fighter jets.

At the time, Pawley didn’t have the paperwork to prove it.

Now he does.

Cabinet documents obtained by the Winnipeg Free Press through an access request show Mulroney was briefed regularly throughout the summer of 1986 about the matter, which saw Manitoba-based Bristol Aerospace ultimately lose out on a 20-year, $100-million contract to Quebec-based Canadair. Memos suggest he was heavily involved in figuring out alternative plans and consolation prizes to reduce the outcry he and his government knew would result from favouring a Quebec-based firm that hadn’t actually won the competition on merit.

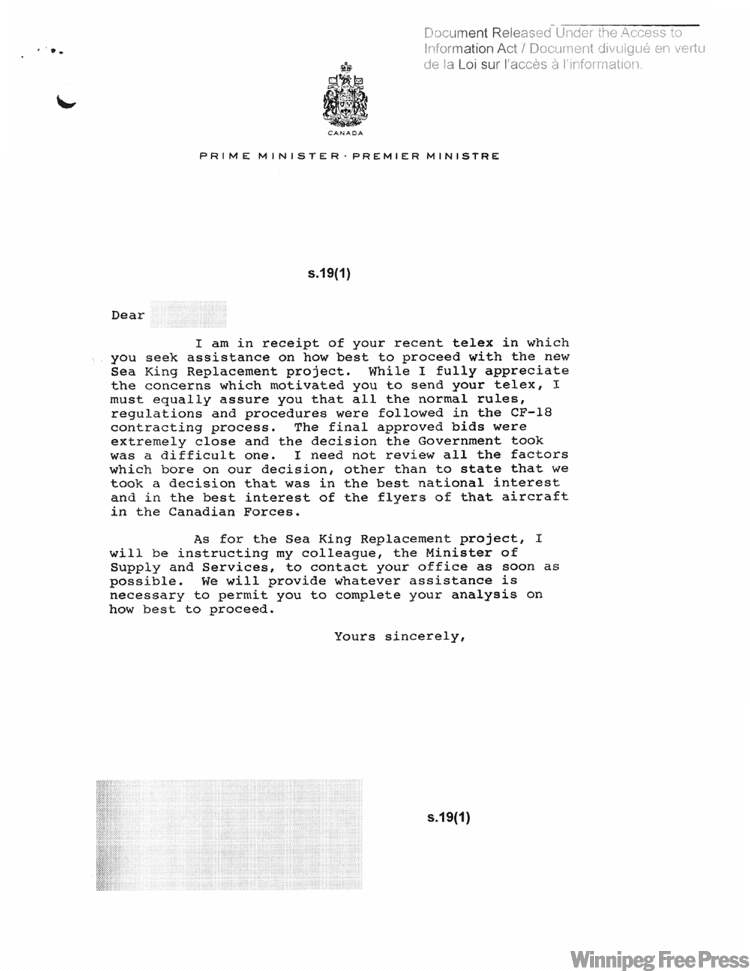

But when Pawley spoke by phone to Mulroney about the contract on Oct. 23, 1986, Mulroney assured him not only had a decision not been made, Mulroney hadn’t even been brought up to speed on what was happening.

"He said he hadn’t even studied the file," said Pawley.

In fact, the documents show Mulroney was informed about the contract and the recommendation it go to Canadair on June 16, more than four months earlier, and he knew as early as Oct. 9, that a decision had been made. The cabinet and Mulroney’s senior staff had spent much of the previous five months embroiled in battles over it.

Giving the contract to Canadair was entirely a political move — Quebec government and union leaders were demanding the work, and their province had more seats at stake in the House of Commons. Canadair was a Crown corporation up for sale in 1986. One of the documents notes if Canadair weren’t given the contract, the government would have to bail it out.

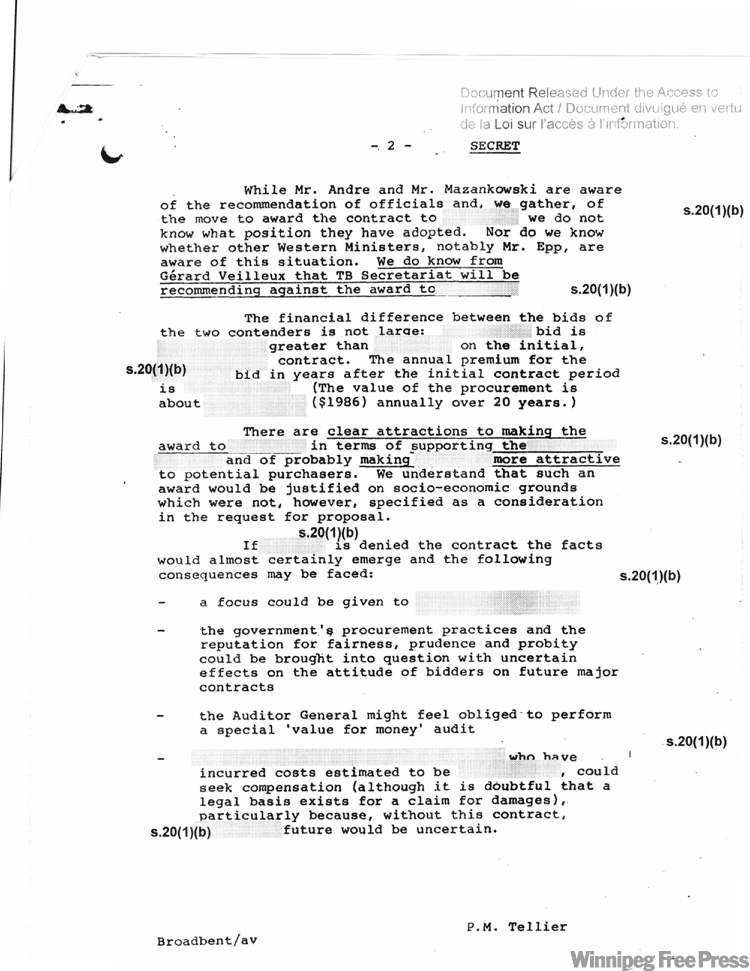

However, the government also knew Bristol was in a precarious situation, as another memo from Tellier to Mulroney warns Bristol might seek financial compensation for the costs it put into the bid because without the CF-18 work, Bristol’s "future would be uncertain."

Pawley, who now lives in Windsor, Ont., said the CF-18 decision clouded the remainder of his time as premier and left already strained relations with the Mulroney government incredibly frosty.

"I distrusted him," said Pawley. "Our relationship was never warm, but this certainly cooled the relationship."

A 24-year-old CF-18 contract may sound like ancient history, but the decision has long been considered a crucial moment in Canadian politics. Western conservatives, already disillusioned with Ottawa after the National Energy Program and the Pierre Trudeau era, were slowly realizing that perhaps their own guy was no better.

It fractured the right in Canada and spawned the Reform Party, which in 1993 helped reduce the once-mighty Progressive Conservative party to two seats in Parliament. The Reform Party principles — which counted among its original members Stephen Harper — often form the political basis for today’s Conservative government led by Harper. For years, the Reform’s mantra was that the West wanted in. When Harper was elected many felt that had finally been achieved, but there are still divides between Mulroney-era and Reform-era Conservatives.

In his book, The New Canada, Preston Manning calls the CF-18 decision the one that confirmed "a growing suspicion that Mulroney Conservatives had the same central Canadian bias as Trudeau."

Nobody bought the Mulroney team’s spin that the contract had gone to Quebec fairly or because of some bizarre need to prevent CF-18 technology from going to foreign-owned companies. Bristol Aerospace in 1986 was owned by Rolls Royce, based in England.

Within a year of the CF-18 decision, the Reform Party was born. Its founding conference was held in Winnipeg in October 1987. Manning was elected its first leader. The conference included an entire session on the CF-18 situation by the president of the Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce.

The notion of CF-18 rears up again whenever Manitoba fears it isn’t being treated fairly by Ottawa, be it the recent loss of an HIV vaccine manufacturing operation to competing with Quebec City for an NHL franchise.

University of Manitoba political expert Paul Thomas said the CF-18 debacle was something everyone could understand.

"It brought to the forefront an emotional level of debate that was very timely for the fledgling Reform Party," said Thomas. "The event has lasting historical significance."

It may have happened more than two decades ago, but Pawley is still angry about CF-18.

"I was furious. I am furious," said Pawley. "I was just shocked."

His wife, Adele, vividly recalls lying in bed listening to CBC morning radio on Oct. 31, 1986 and hearing that Canadair had won. Mulroney hadn’t even kept his word to the premier that he would give him a head’s up.

"He got out of bed in a shot," said Adele.

Pawley immediately called meetings with cabinet ministers and Bristol officials. He announced to the media that the prime minister could not be trusted and days later flew to Ottawa with a team of Manitobans to lobby the government to change its mind. His reception from Mulroney was icy. Pawley said the prime minister was irate about his comments about trustworthiness.

"He was very upset with me," said Pawley.

Pawley also said Mulroney defended favouring Quebec, pointing out that he had supported Pawley during the Manitoba French language debates in 1984 and that Manitoba had a lower unemployment rate than Quebec.

THE extent of the anger in Manitoba, particularly from Conservatives, surprised Pawley. He visited Morris shortly after the decision and remembers Conservative voters talking loudly about Manitoba being shafted.

"I think it was the beginning of the disenchantment with the Conservative party," said Pawley.

The cabinet documents were kept under wraps for 20 years. The Free Press has obtained 78 pages of them. Some information, mostly related to third-party companies, is blacked out in many of the letters, memos and communications plans.

The package begins with a June 16, 1986 memo to Mulroney from Privy Council clerk Paul Tellier, informing the prime minister about a contract for CF-18 maintenance that a cabinet minister had recommended be "awarded to the firm judged to be second in the evaluation" by an expert panel from the departments of Defence, Regional Industrial Expansion and Supply and Services.

Although company names are generally blacked out in the documents, it says one company’s bid was lowest and that one had "the significantly better technical performance evaluation." It has long been known that was Bristol Aerospace.

Regardless, Stewart McInnes, the minister of Supply and Services, was recommending the government go with the "second lowest bidder."

Two possible reasons are listed for giving the bid to Quebec: one is blacked out; the other is to make Canadair more attractive to buyers. The Crown corporation was for sale and would ultimately be sold to Quebec’s Bombardier Inc. that same year.

Tellier’s memo warned that granting Canadair, not Bristol, the contract would generate significant problems, including a blow to the government’s reputation for fairness, which could affect future contracts and bidders. The auditor general could also conduct a review, Tellier said, and noted Bristol could seek compensation for its costs of preparing the bid, which had been a seven-year process.

From the start, Tellier and others repeatedly warned that awarding the contract to Canadair was a significant communications nightmare. At one point, Tellier even told Mulroney to stop delaying the decision because it only made things worse and made the government look indecisive.

IN the days and weeks that followed, Mulroney had staff seek solutions, including trying to convince Defence officials to split the contract, something they clearly didn’t want to do. Memos to Mulroney dated June 18, June 25 and Aug. 7, all refer to trying to get Defence officials to agree to divide the contract between Bristol and Canadair.

At first, DND said no outright, and Mulroney was given the option of awarding smaller defence contracts to Bristol, including a retrofit of CF-5 and Tutor aircraft, which were shorter in length and less valuable in jobs and money. Also, it made no sense to give the CF-5 contract to Bristol because Canadair actually made those planes.

Subsequent memos noted DND feared the cost overruns of splitting the contract, the time it would take to renegotiate with both firms and the security issues associated with having two companies do the work. DND came closest to relenting on the split contract in August, but wanted the bigger portion of the work and the prime contractor designation to go to Bristol because it had "received the better evaluation."

However Mulroney was again warned about Quebec’s insistence that no major aerospace work go outside Quebec, which was supposed to be Canada’s aerospace hub.

Tellier said Quebec would consider anything less than being the prime contractor "half a loaf" and not at all acceptable.

Throughout the summer, various Mulroney cabinet ministers and government bureaucrats met, debated and corresponded about the problems. There were calls for communications plans, concerns about leaks, and amid it all, an intense lobbying effort from both Quebec politicians and aerospace unions.

The reasons for giving the contract to Quebec expanded and shifted throughout the summer, although the sale of Canadair remained a constant issue. There clearly were splits in cabinet. One memo even recommends keeping the issue out of cabinet because of the regional battles at play.

By Oct. 9, the government’s direction was clear. Cabinet and Treasury Board hadn’t yet met to finalize the decision but a memo to Mulroney from Tellier that day outlines a list of all government announcements that could be made that fall, including trying to make announcements for the West that might soften the CF-18 blow.

On the list of those announcements attached to the memo, it says: "CF-18. Outcome clear? Yes. Canadair." Two weeks later Mulroney told Pawley on the phone he hadn’t been briefed on the matter and no decision had been made. A week after that, on Halloween morning, the contract was announced.

In the weeks that followed, Mulroney received a barrage of letters from Manitoba politicians, union leaders and others demanding he reverse course and give the contract to Bristol.

In his standard replies, Mulroney said the decision followed normal rules and procedures.

"The decision was not an easy one but ultimately, by the narrowest of margins, my government made the choice which we regarded as being in the best national interest," he wrote.

mia.rabson@freepress.mb.ca