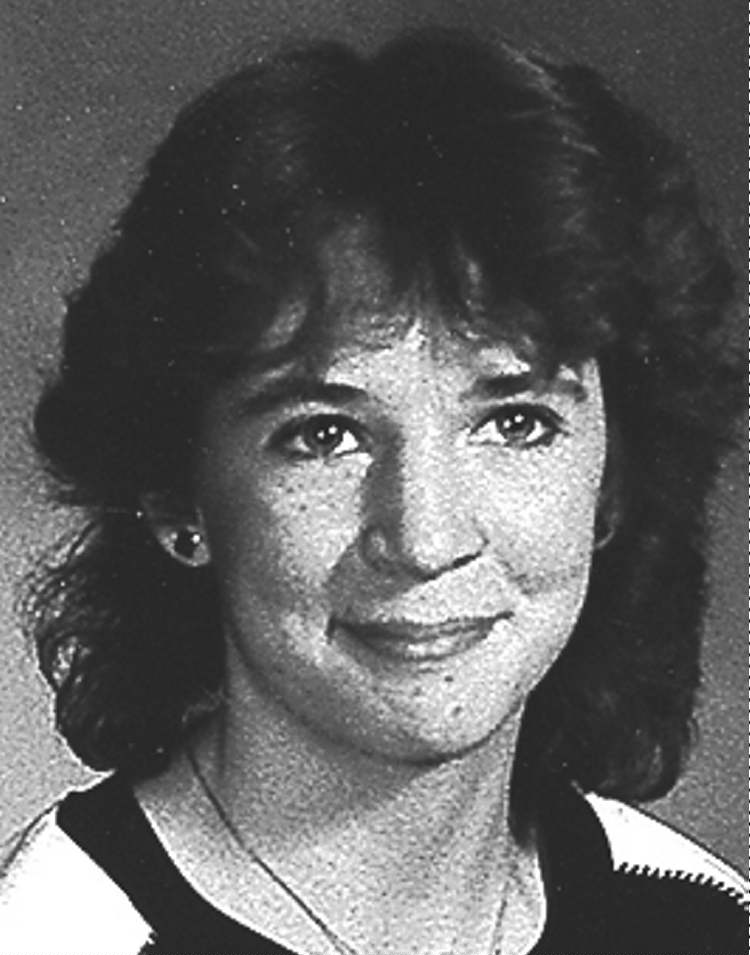

Wilma Derksen has a vision for helping crime victims’ families

A house for healing

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/03/2013 (4717 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Swimming against the current is hard work. Just ask Wilma Derksen.

In 1984, Derksen’s 13-year-old daughter, Candace, was abducted as she walked home from school and later murdered. Her killer, Mark Grant, was not charged and convicted until 2007. In the 23 years between losing her daughter and finding the man who killed her, Derksen learned to navigate, and then overcome, the currents of emotion.

Initially, in a bid to relieve her own suffering, Derksen toiled within the victims’ rights movement. With a quiet and articulate elegance that is legendary among those she has touched, Derksen quickly became a nationally recognized advocate for the pain and suffering of victims, both at the hands of criminals and from the justice system itself.

As a result of this experience, she has had a unique view of the victims’ rights movement, the justice and correction systems and the politics that envelops all three. Bottom line? She is not happy with the current state of being for victims of crime.

After years of meetings, fundraisers and debates, she has come to the conclusion an entirely new approach needs to be undertaken. And that’s where Candace House comes in.

Working with the local chapter of the St. Leonard’s Society, a non-profit group that provides support to ex-offenders, Derksen is forging ahead with a plan to create an oasis of calm for the family of victims of crime. St. Leonard’s has agreed to change its name and become Candace House, a soon-to-be-established home near the downtown Law Courts where families can escape the emotional volatility of trials and police investigations and get support from people who understand their suffering. It will also be a place where victims and their family can get an honest and frank explanation of how the justice system works and what role they will play in the outcome.

A lifetime as a victims’ rights advocate has taught Derksen many things. First, initiatives that only seek to increase punishment for offenders will never help victims heal. And far too many players in the justice debate are using the grief and rage of victims to pursue their own political agendas.

“I’m really not the most popular ‘victim’ right now,” she said. “I’ve had lots of attention, and I’ve been part of advising a lot of groups and committees. But there isn’t a policy or law right now that deals with what victims need.

“Nobody really knows victims or how to deal with the emotions of being a victim. There are too many conflicts of interest and too many people using us for their purposes.

“We really need to isolate the needs of the victim and focus on that.”

— — —

Candace House traces its origins to, of all places, Stony Mountain Institution north of Winnipeg.

In 1996, Derksen agreed to meet with a life prisoners’ support group within the prison. The theory was her visit would be beneficial for the prisoners, a way of getting them to empathize with a woman who had lost so much to violent crime. Derksen said she agreed, in part because she also thought it would be beneficial for her — a chance to confront the lingering rage and hate she carried since Candace’s death. The experience, Derksen said, was profound.

“The whole thing just astounded me,” she said. “It changed my life.

“There were 10 men in the room with me. They were pretty intrigued with me, just as I was intrigued with them. I will tell you I really gave it to them. How what they had done had harmed so many people. To my surprise, they responded. They answered my questions honestly.”

The inmates were so moved, they created the Candace Derksen Fund to support victims’ services. They held events within the institution to raise money and asked groups on the outside to support their cause. The Winnipeg Foundation would later offer to administer grants. Although it did not result in a lot of cash, Derksen said the gesture was extremely moving. More importantly, the whole experience of confronting the inmates, and their response, started to change the way she thought about victims’ rights and support services.

Currently, she noted, there is a lot of lip service paid to supporting victims of crime. Victims’ rights legislation and mandated victim-impact statements are baked into the lexicon of the justice system. However, Derksen said she is often concerned victims are the political footballs of the justice system, and support for victims is still mostly an afterthought.

That support usually comes from legislators, who are almost solely focused on increasing punishment. While that may be justified in some cases, it really does very little to meet the needs of victims and may, in fact, prolong their suffering.

Derksen said underlying many crime-and-punishment initiatives is a message to victims that they can somehow gain control of the outcomes of the criminal justice system. That is unfair to victims, she said, because it’s not really true, and even if it were, it might not be the best approach.

“The justice system is complex and difficult,” she said. “To give control of it over to people who are really emotionally crippled is just dangerous. Victims don’t need control over the justice system; they need gain control over their lives. And new laws and victim-impact statements don’t do that.”

— — —

Following Mark Grant’s conviction, Derksen said her husband, Cliff, “came alive again” after years of self-imposed isolation, grief and anger. An artist, Cliff rediscovered his creative spark and began to sketch. One of the first pieces he did was of the couple’s bare feet.

Derksen said she and Cliff would often remove their shoes in an effort to relax during the Grant trial. Somehow, that image became a touch point in the relief and healing that came after the trial. A few friends saw the sketch and were so moved by it that the Derksens began to give out copies as gifts to those who had supported them through their ordeal. Eventually, they began to sell the sketch for donations. This created a new source of revenue for the fund started by the lifers.

This new initiative seemed to be leading Wilma Derksen to some specific purpose. And yet, she said she was unsure about exactly how best to help victims. Over the years, she had worked with so many groups, from the Mennonite Central Committee to the John Howard Society and the Family Victims of Homicide, and while all did valuable work, none seemed to completely meet victims’ needs.

Working with some of her closest supporters, including former John Howard Society executive director Graham Reddoch, and Floyd Wiebe, a victims’ advocate whose son, TJ, was also a murder victim, she began to focus on what victims really needed. “We all really arrived at the same idea — a house no more than a 20-minute walk away from the courthouse, where victims could feel safe.”

Derksen said she strongly believes victims need to stop dwelling so much on crime and punishment and start focusing more on their own needs. She said she lived with a lot of rage and hate until Grant was finally brought to justice. Once he was convicted, she realized how heavy the burden on her had been and how little relief she got from victim-impact statements and increased sentences for offenders.

The promise of Candace House is to, for the first time really, create a place where victims come first, where they are in control, Derksen said.

So much of the justice system is beyond their control and must remain that way to ensure the fairness of the proceedings, she added. However, that does not mean we can continue to leave victims on the sidelines as afterthoughts.

“Underneath all the emotion and pain, there is a wisdom in people who have experienced crime,” she said. “However, we haven’t really tapped into that because we’re encouraged to be so focused on punishment.

“This isn’t just about punishment. If that’s all you think about, you can be dismissed as people consumed by rage. And in that rage, we never really heal.”

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Dan Lett is a columnist for the Free Press, providing opinion and commentary on politics in Winnipeg and beyond. Born and raised in Toronto, Dan joined the Free Press in 1986. Read more about Dan.

Dan’s columns are built on facts and reactions, but offer his personal views through arguments and analysis. The Free Press’ editing team reviews Dan’s columns before they are posted online or published in print — part of the our tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, March 13, 2013 9:26 AM CDT: replaces photo

Updated on Wednesday, March 13, 2013 12:22 PM CDT: amends wording