Disclose the full police report at Sinclair inquest

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/08/2013 (4465 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

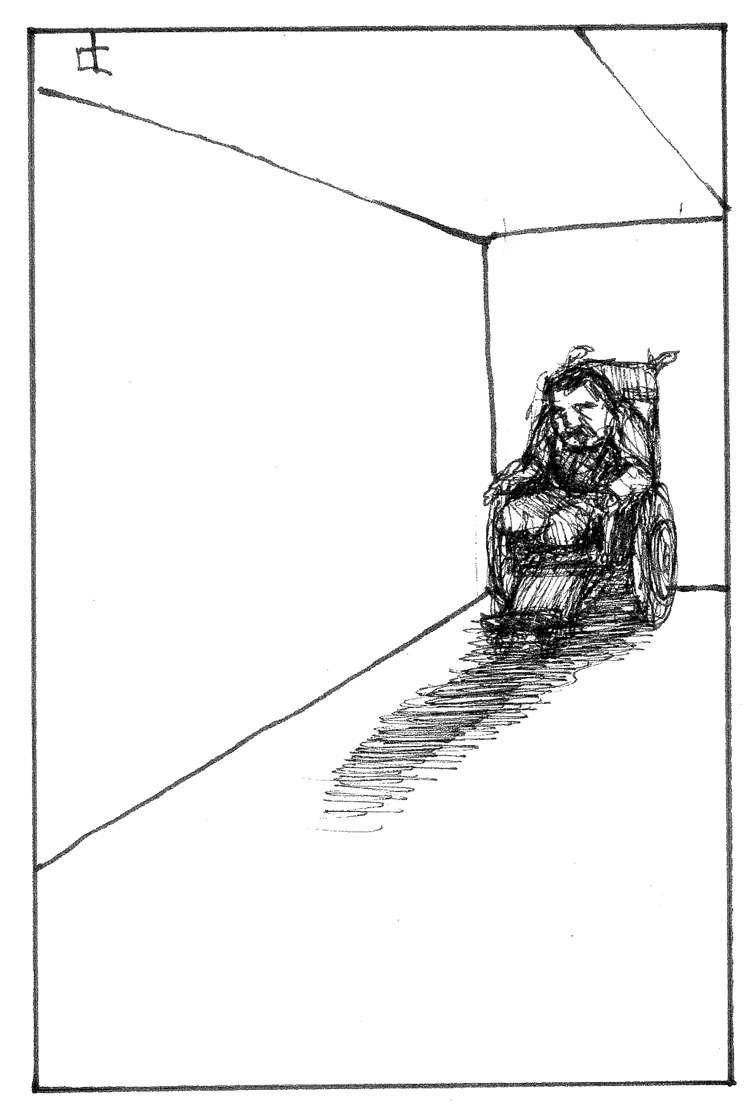

The inquest into the 2008 death of Brian Sinclair at Health Sciences Centre’s ER has heard a controversial police investigation report will not be tendered as evidence. If the full report is not made available for public scrutiny, Manitobans may be deprived of a critical element in the story of how Mr. Sinclair died in the waiting room, and the roles of HSC staff in that affair.

An inquest is tasked precisely to find the circumstances and cause of an untoward death, particularly when public authorities were involved. But as with public inquiries, inquests are held to serve a broader public interest, as part of the accountability of those authorities.

The Winnipeg Police Service investigation was launched in the wake of the outcry that Mr. Sinclair, who died of a bladder infection from a blocked catheter, could have sat for 34 hours in the waiting without seeing a doctor or receiving medical attention. Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Thambirajah Balachandra revealed sometime after the death that the double amputee, who had a severe speech impediment, was approaching the triage desk before being redirected to the waiting room.

The police report was forwarded for opinion on criminal charges — failing in professional duty can be considered criminal neglect — to an out-of-province Crown attorney, who recommended none be laid. The public ought to be able to scrutinize that decision, especially since a critical-incident review by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority will not be filed as evidence with the inquest, as per provincial statute.

Murray Trachtenberg, representing the Sinclair family, said Crown counsel David Frayer has provided Vol. 1 and 2 of the report to lawyers representing the various parties, but he wants all the exhibits the police report referred to but were not filed at the inquest.

The province says police reports are not filed as evidence at inquests, but they should be, particularly in a case that involves allegations of extraordinary neglect by medical and hospital personnel. Making public pieces of the report — which may happen as lawyers examine witnesses — is insufficient as it strips the report of scope and context. The public cannot rely on the lawyers of parties serving other interests to speak for the public.

The Fatality Inquiries Act, both expressly and in spirit, speaks to the role of inquests in protecting public interest, presided over by provincial court judges to ensure that review is full and transparent. A document can be redacted to protect personal privacy and irrelevant details. Justice Minister Andrew Swan must recognize this and lift any impediment to the WPS report’s full disclosure.