Manitobans’ role in Great Escape uncovered

Book details made-in-Canada ingenuity behind famous Second World War incident

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/05/2015 (3795 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The 30th prisoner from the Allied forces to go through the 102-metre tunnel in the famed Great Escape of the Second World War knocked out a shoring, causing the ceiling to collapse.

Hank Birkland, from the tiny village of Spearhill in Manitoba’s Interlake, was stationed at the tunnel’s midway point, helping push PoWs through the hole as long as a football field. Birkland, nicknamed Big Train because of his short but solid build, crawled through the tunnel, dug the man out and reset the posting. Birkland then cleared debris from the track so the next man could pass.

Birkland wasn’t the only Manitoban involved in the extraordinary mission. At the front of the tunnel, Gord King from Garfield Street in the West End, who was scheduled to be the 141st PoW through the hole, pumped air into the tunnel all night long so his fellow prisoners wouldn’t suffocate.

The sorrily overlooked role of Canadians in one of the most brilliant and audacious escapes in military history — in all history, really — is finally being acknowledged with the publishing of Ted Barris’s book, The Great Escape: A Canadian Story (Dundurn Press).

The fact Manitobans were involved in the famous incident has seldom been reported.

Barris will be in Winnipeg on Thursday for a reading and book signing (7 p.m. to 9 p.m., Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada) hosted by the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, Manitoba chapter. There is no admission charge.

About one-third of the operatives in the massive 1944 prisoner escape were Canadian. Then why has the Canadian role in the Great Escape received so little attention?

Barris blamed it on good old Canadian modesty, in an telephone interview from the Toronto area.

Hollywood recognized a good story when it saw one and made it into a terrific movie in 1963 starring Steve McQueen. But like the film Argo, the Oscar winner for best picture in 2013, it played with the truth and was heavily Americanized to appeal to audiences in the United States. Only two Americans, one flying for the Royal Air Force, the other from the Royal Canadian Air Force, had involvement in the Great Escape.

The character played by actor James Garner was, in real life, a bomber pilot named Barry Davidson from Calgary; Charles Bronson’s character in charge of tunnel construction was actually Wally Floody from Chatham, Ont.; Bronson’s assistant, played by British actor John Leyton, performed the duties of Floody’s right-hand man, Spitfire pilot Hank Birkland; Donald Pleasance played the forger, who in reality was bomber pilot Tony Pengelly from Truro, N.S.

Stalag Luft III was a PoW camp for Allied forces airmen near Zagan, Poland. The airmen were afforded privileges not available to other PoWs that allowed them movement to carry out their elaborate scheme. Stalag Luft III held about 10,000 prisoners, but it was among the 2,500 Commonwealth flyers in the north compound that the escape was launched.

The escape was breathtaking in its detail and collaboration of so many people.

The tunnel was dug with whatever they could get their hands on including pans, tools fashioned out of sheet metal and spoons. They had a security system initiated by the guy who hung up the laundry on a clothesline, and arranged it in such as way as to notify the tunnel digging crew when German inspection guards were coming.

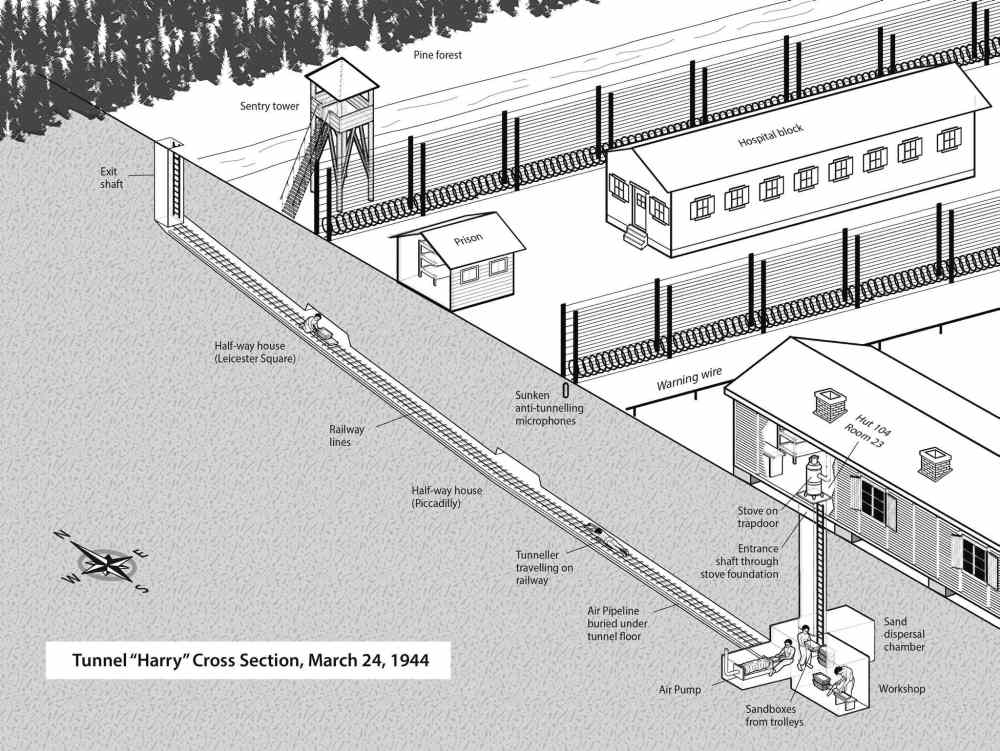

According to Barris, an electrician reasoned there is always extra slack wiring in walls, so PoWs opened walls in their barracks and removed the slack for wire to help light the tunnels. They constructed a crude trolley system out of extra boards from their beds. The trolleys were made of buckets, and the wheels out of wood wrapped in tin from soup cans. They put carpet on the rails to deaden the sound. The PoWs laid on the trolleys and dog-paddled their way out. (The movie shows the trolleys being pulled by ropes but Barris insists the riders pushed them along with their arms.)

Those who could speak German gave language lessons to others to improve their chances of blending in once out the tunnel. Documents were forged so the prisoners could pass through checkstops across Europe. A British tailor recut and fashioned clothing, using vegetables (such as beets) for dye, to make prisoners look like civilians, some as labourers and some as businessmen. The businessmen had briefcases that looked real but were actually made out of cardboard.

They initiated the digging of three tunnels, called Tom, Dick and Harry, in case one tunnel was discovered. The tunnels were three metres below surface, and only about 0.6 metres wide.

“Tom” was found out, and that brought about a crackdown that caused tunnel construction to cease through the autumn months. “Harry” was the tunnel eventually used on the night of March 24 and early morning March 25, 1944.

Pilot Gord King was the air-pump operator, a bellows system for injecting oxygen into the tunnel so diggers, and later the escaping men, wouldn’t suffocate, said his daughter, Cathy King, in a telephone interview. King is 95 and in assisted-living quarters in Edmonton. He has memory problems, said Cathy, who is a former Canadian women’s curling champion.

King was one of the 200 or so “penguins,” as they were called, who helped disperse the sand and dirt excavated from the hole. They were called penguins because that’s what they looked like. Wearing long coats loaded with dirt, they walked outside and released the dirt out their pockets and down their pant legs.

A total of 76 men got out in the escape that fateful night before a German guard, perhaps hearing something, veered off his regular course and almost stepped into the exit hole. Out of the 76 escapees, 73 were rounded up within days.

Adolph Hitler showed himself incapable of even a shred of respect for human endeavour, and ordered the execution of all escapees. In addition, he had two electricians at Stalag Luft III shot for not reporting missing wiring used to light the tunnel. A supervisor at the prison camp was also shot.

Hitler was eventually talked down somewhat and ordered 50 escapees be executed. It wasn’t like the Hollywood film where the escapees were shot at once by firing squad. Rather, they were taken out two or three at a time and shot by Gestapo agents.

Birkland was the 51st PoW out of the hole. He was one of nine Canadians who made it. All were recaptured. For all his work digging the holes, suffering from claustrophobia and frequently throwing up from lack of oxygen, his freedom was brief. Birkland was one of six Canadians killed.

The executions were in violation of the Geneva Convention protecting PoWs. Germany claimed all 50 had been shot while trying to flee custody from the Gestapo.

Two Norwegian pilots and one Dutch pilot were the only escapees to make it back safely to their home countries.

Barris has given more than 250 presentations across the country since his book was released 18 months ago. It has topped bestseller lists and won the 2014 Libris Awards non-fiction book of the year (shared with Chris Hadfield’s An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth).

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Monday, May 25, 2015 6:34 AM CDT: Replaces photos, adds photo

Updated on Monday, May 25, 2015 7:29 AM CDT: Adds slideshow

Updated on Monday, May 25, 2015 11:11 AM CDT: Corrects neighbourhood of Garfield Street.