Still taking ‘Indian’ out of the child?

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/05/2015 (3820 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For some, the horrors of Canada’s residential school system are viewed as ancient history. For those who experienced it, the scars remain. And for many who look at the statistics of First Nations children seized by child welfare agencies in Manitoba the question becomes is the nightmare really over?

On Tuesday, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission delivers its main findings in Ottawa. Its goals, in part, are to acknowledge Canada’s residential school legacy, provide a safe place for survivors to talk about their experiences, promote awareness of the residential school system and to create a historical record of the system for future educational purposes.

Canada joins other nations in attempting to redress legacies of mass abuses of human rights by relying on the formation of a truth commission. South Africa, Liberia, Indonesia, the United States, Chile and Rwanda have also implemented similar forms of commissions to respond to the aftermath of such violence. In most cases, truth commissions were formed after major civil uprisings and in a transition toward full functioning democracies. For example, in South Africa, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed in 1995 following the end of apartheid.

There are two important differences in Canada. We are hardly a fledgling democracy. The residential school system was allowed to prosper at a time when Canada was a respected leader for democracy.

And while Oka, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People and the rise of indigenous activism may have been the push behind the commission, Canada was never involved in a civil war with First Nations.

More importantly, while the state played a major role in truth commissions in other countries, in Canada, it’s not clear what role the Harper government will play. Even the chairman of the TRC, Murray Sinclair, is not expecting much from Mr. Harper. Instead, he’s hoping charities and non-profit groups, schools and educators, academics and neighbourhood associations will engage to discuss the findings.

Unbelievable that with all this time and attention spent on the TRC, the federal government can’t be counted on to show true leadership.

As Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin says, Canada is guilty of attempting a cultural genocide. In a speech last week, Justice McLachlin said “Taking the Indian out of the child” — promoted by Sir John A. Macdonald as a solution — is assimilation and cultural genocide.

Assimilation is something the 1998 Royal Commission on Aboriginal people talked about in its report released after 178 days of public hearings. Its main finding was the policy direction of the Canadian government has been wrong. That assimilation isn’t working. That Canadians need to see First Nations as nations.

The release of the executive summary of the TRC occurs at an interesting time in Canada’s history. Next week is the 25th anniversary of the death of the Meech Lake Accord, brought about in part because aboriginal people were not properly consulted on constitutional reform.

The concept of nationhood for First Nations still has a long way to go. But recognizing the self-government of First Nations rather than trying to assimilate could help. It was sought in constitutional discussions following the death of Meech and it remains top of mind for most First Nations organizations such as the Assembly of First Nations.

But, here we are 17 years after the Royal Commission, 25 years after the death of Meech. Children in Canada are being seized from their First Nation homes in numbers far greater than in the residential school system. They are put into the child welfare system where there have been countless stories of abuse, neglect and death.

And it begs the question: Are we still trying to take the Indian out of the child?

History

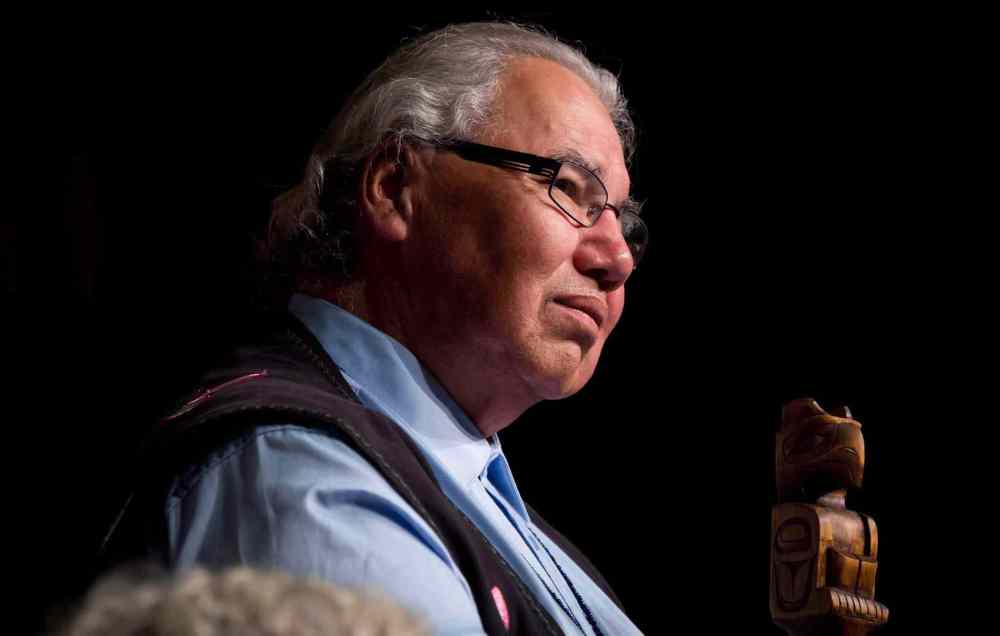

Updated on Monday, June 1, 2015 8:39 AM CDT: Adds photo