City’s heritage hero: McDowell considered founding father of historic-preservation movement

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/12/2015 (3616 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

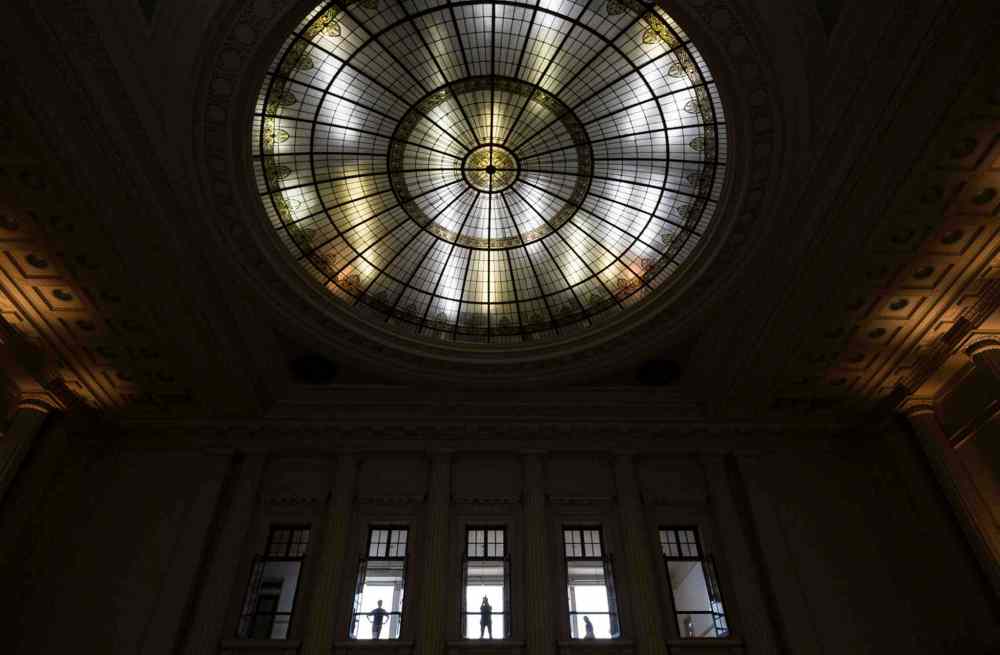

On Dec. 3, members of the city’s heritage community gathered at the Millennium Centre on Main Street to celebrate David McDowell, considered by many to be the “father” of Winnipeg’s heritage-conservation movement.

It was a fitting venue given that nearly four decades earlier, McDowell led the charge that saved the building from the wrecking ball and spurred public and political support in favour of protecting similar buildings for decades to come.

The decade between the late 1960s and 1970s were not kind to Winnipeg’s building stock. In the greater downtown area, entire square blocks of houses, schools, churches and commercial buildings were being razed to make way for new megaprojects that were intended to turn around its sagging fortunes.

Some developments were realized, including Lakeview Square, the Centennial Corporation’s concert hall/museum/planetarium complex and one of the three Trizec towers proposed for Portage and Main.

Much of this land, though, never saw redevelopment and has remained surface parking lots to this day.

David McDowell, a Brandon-area geography teacher, came to Winnipeg with his wife, Linda, in 1968 to pursue his master’s thesis at the University of Manitoba.

He remembers what he refers to as the “blockbusting” that was going on at the time, and he, “Wait a minute… what are you doing to our community?”

Already a longtime executive member of the Manitoba Historical Society (MHS), McDowell took an active role in one of its most ambitious projects.

In 1970, it purchased Dalnavert, a Carlton Street rooming house that was once the home of Hugh John MacDonald. It was restored to its Victorian splendour and opened as a museum in 1974.

“That cast us (the historical society) from being a group that dealt with papers and walking tours to being truly preservationists,” he said.

‘Here was this little teacher, who was not a radical, out suddenly leading a group of concerned citizens’

— David McDowell

Another player in the rediscovery of the city’s heritage buildings at that time was the Old Market Square Association. It was made up of investors who had begun buying up long-forgotten warehouses in what is now known as the Exchange District. They, in turn, offered affordable space to young entrepreneurs who created an eclectic mix of retail shops, from pottery makers to furniture warehouse outlets. In 1976, Old Market Square hosted its first annual summer outdoor market, which brought thousands of people to the area.

McDowell says Winnipeg lagged a decade behind a national wave of civic interest in historic districts led by cities such as Vancouver and Montreal. A key player in the rediscovery of historic streetscapes at the time was the Heritage Canada Foundation. Intrigued by the grassroots interest finally taking root in Winnipeg, in the fall of 1976, it announced a $500,000 grant program Old Market Square building owners could access to improve their buildings.

Two years later, the foundation purchased and renovated the Hammond Block at 65 Arthur St., in its words, “to set about demonstrating how an interior and exterior refurbishment could be viable and successful.” That same year, the foundation was instrumental in getting the province and city to partner in an organization called Heritage Winnipeg that would advocate for heritage buildings and their upkeep in the Old Market Square area.

Even with this increased level of interest in Winnipeg’s historic buildings at both the local and national level, the City of Winnipeg didn’t so much follow along as it got “pushed along” by the growing movement to offer things such as improved streetscaping in the Old Market Square area, McDowell says.

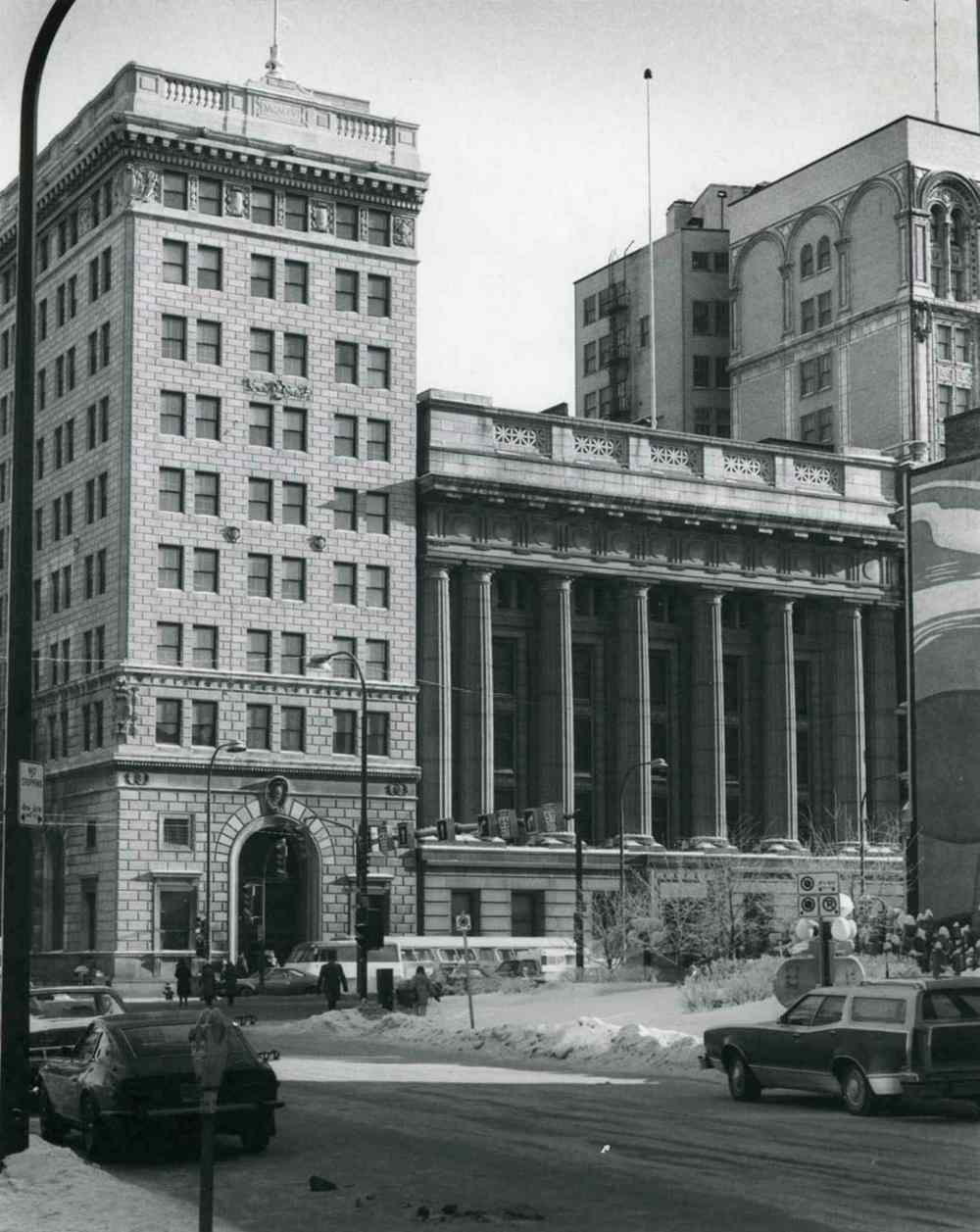

One area where the city had truly fallen behind its national counterparts was offering protection against demolition to its most architecturally significant buildings. The dozen or so grand, old banking halls that made up Banker’s Row, for example, were arguably among some of the finest structures of their type in North America, yet they were under the greatest threat.

Through the 1970s, all but one of the big four banks — the Bank of Montreal being the exception — abandoned their old city headquarters, leaving them vulnerable to the wrecker’s ball.

McDowell credits a couple of progressive young planners working for the city, Chuck Brook and Steve Barber, and planning commissioner Dave Henderson for working behind the scenes to put together a heritage-building bylaw similar to those that were in place in other cities. It was slow going, though, as the political will to fast-track its implementation was not yet there.

A line in the sand for the growing community of heritage supporters was drawn out front of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce’s old Main Street headquarters. Having relocated to the Richardson Building in 1970, the bank applied to the city in September 1978 to have both the building at 389 Main St., now the Millennium Centre, and the neighbouring Bank of Hamilton Building demolished so it could offer parking for their customers.

“A lot of us just said ‘Whoa, this just can’t happen.’ These buildings were icons for us,” says McDowell.

He told the Free Press at the time, “They are still sound and could be recycled. Winnipeg is a very lucky city to still have many of its old buildings, and it is very important these be maintained so that we can have a variety of buildings and an interesting facade on our downtown streets.”

Two months after the bank’s request for demolition permits was submitted, it was still awaiting a decision, and the city’s fledgling heritage bylaw was finally ready to go to council for approval. If there was a chance to save these buildings, it would have to be with that bylaw in place.

McDowell found himself playing a central role in gathering the public support needed to push council into passing the bylaw.

“Here was this little teacher, who was not a radical, out suddenly leading a group of concerned citizens, and it was the citizenry that really came to the fore and said ‘sign the petition,’ ” he said.

The campaign culminated with a public protest Nov. 20, 1978, the day of the city council meeting. McDowell organized a group of 100 or so people, including members of the historical society and Heritage Winnipeg, the Old Market Square Association, architecture students and the general public, for a first-of-its-kind protest in Winnipeg.

“Pickets that were put together in my basement were unloaded at the corner of Portage and Main,” he said. “We marched into the -30 wind and took on city hall and were there until midnight.”

In the end, the bylaw was passed thanks to councillors such as Al Ducharme and June Westbury, who led the charge from the chamber. The bank agreed to a postponement on the final decision on its demolition permits, which ended up lasting about a year. That allowed time for the buildings to be evaluated and placed on the city’s historical-buildings inventory as Grade I, effectively preventing their demolition.

McDowell is modest about his role in getting that bylaw passed.

“I was fortunate that I was able to take on a leadership role, with a lot of support from a lot of people,” he said.

“It was not me alone — I was just a catalyst for galvanizing people’s interest.”

George Siamandas, another key figure in the early years of the city’s early heritage movement, credits McDowell with more than that, saying he was “able to bring people together and get things done, including saving the banks and helping create a positive atmosphere for heritage preservation, which has now taken solid root with the success of the Exchange District.”

Retired from teaching, McDowell continues to be involved in various roles with Heritage Winnipeg and the Manitoba Historical Society.

He has also taken on new projects such as the public-education component for both Friends of Dalnavert, which recently took over the museum from the historical society, and the Upper Fort Garry interpretive centre.

He says he is pleased with what has taken place over the last 40 years and is happy he can assist in educating the next generation so they can “pick up the torch” and remain vigilant on behalf of Winnipeg’s built heritage.

Christian Cassidy writes about local history on his blog, West End Dumplings.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, December 20, 2015 7:59 AM CST: Photos changed.