Early cycling group sought to transform city

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/04/2016 (3549 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the weeks to come, thousands of Winnipeggers will dust off their bicycles and take advantage of the city’s growing network of bike lanes and paths. Though such cycling infrastructure is still pretty novel in our city, if the Cycle Path Association of nearly 120 years ago had had its way, they would have been a long-standing feature of our urban landscape.

Mass-produced bicycles hit the market in the late 1880s, but they weren’t cheap. Entry-level models were advertised in local stores at between $65 and $80, a price well out of reach for most whose hourly wages were calculated in pennies.

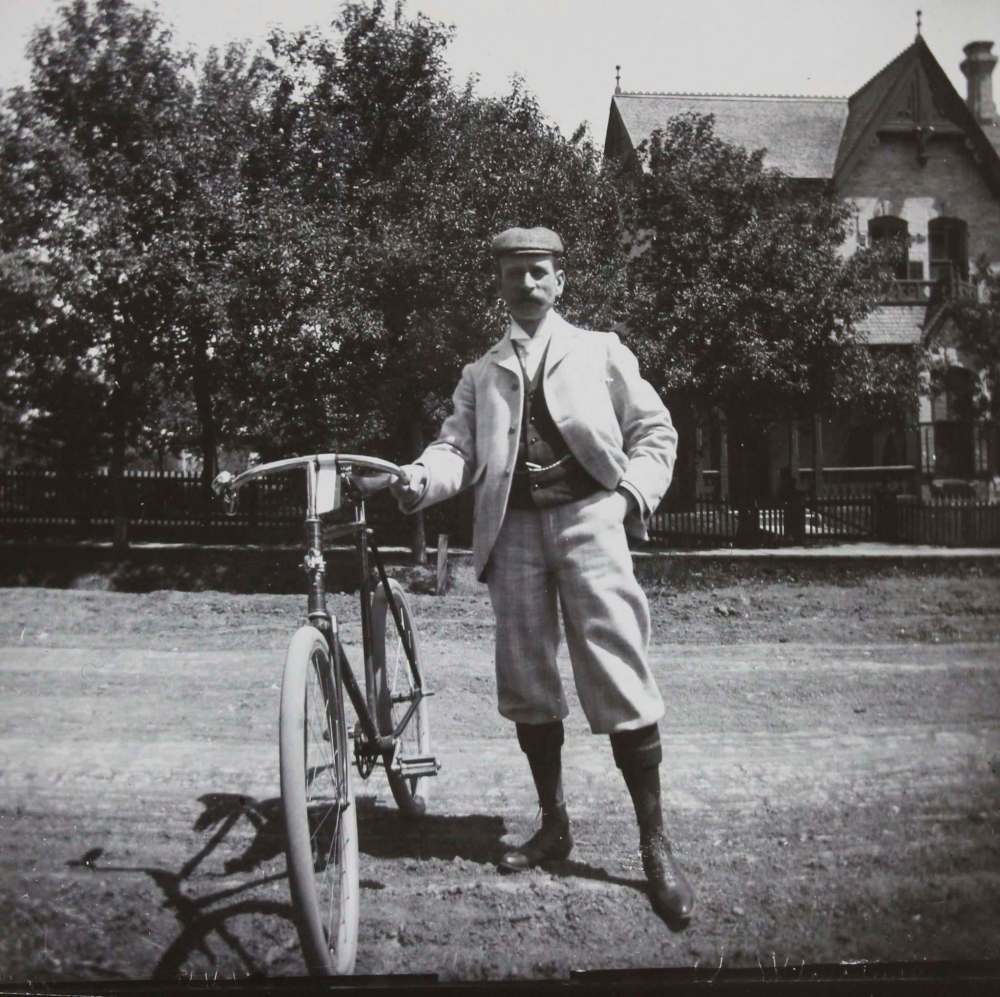

Cycling was therefore a pastime for the rich, consisting mainly of leisurely rides in a park on weekends. For the men, it might have included a membership in one of the city’s two main competitive cycling clubs, the Winnipeg and the Rovers, which met throughout the summer at exhibition grounds and park tracks.

❚ ❚ ❚

Through the 1890s, the price of bicycles fell dramatically. As more people began riding them around the city on a daily basis, the issue of cycling infrastructure became a hot topic.

Winnipeg’s early roads were nearly impossible to cycle on. Their mud or gravel surfaces were criss-crossed with ruts from cart wheels. The shoulders, where cyclists were expected to stay, contained debris and haphazardly installed utility poles.

Asking the city for dedicated paths fell on deaf ears. City fathers struggled to keep up with the demand for basic urban infrastructure such as roads and emergency services. “Soft services” such as parks, cycling paths and libraries would have to wait until after the turn of the century.

On March 24, 1899, a meeting was held at the Criterion Hotel on McDermot Avenue to discuss the creation of an organization that would “take up the question of good roads, paths and other matters affecting the rights, privileges and conveniences of wheel men.” It would be a lobby organization and, through the revenue from the sale of memberships, would build and maintain cycling infrastructure throughout the city.

A couple of dozen businessmen attended, and by the end of the evening, the Cycle Path Association was created.

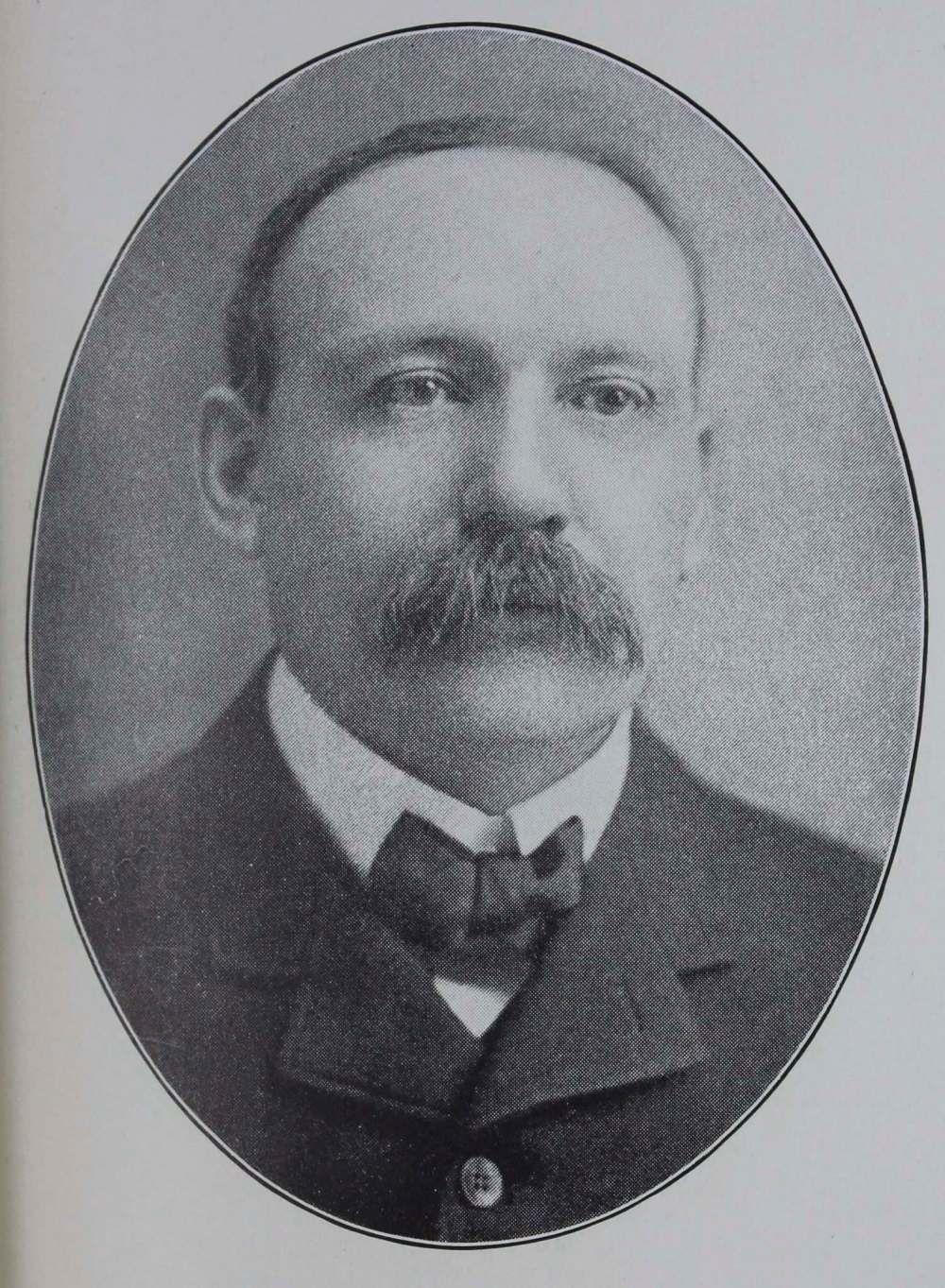

The organization’s president was Frederick William (Fred) Drewry, co-owner of the Redwood Brewery. Drewry was not only active in cycling circles, he was an avid hunter, a patron of the Winnipeg Lacrosse Club and a founding member of the St. Charles Country Club. He foresaw the popularity of bicycles, not just as recreation for the wealthy, but as everyday transportation for many working men and women.

The association’s idea of the ideal cycle path would consist of two directional lanes, each 21/2 feet (0.7 metres) wide and separated by a three-foot (0.9-metre) grass lane. They would be graded and covered in gravel to allow for quick drainage. The cost to build of one these lanes was estimated to be about $208 per kilometre.

To raise the money required for such a network, the association would sell membership tags. The cost was $1 for men, 50 cents for women and 25 cents for children. By early May, about 1,000 tags had been sold.

Its initial construction projects involved upgrading and filling in gaps of the bits and pieces of paths that had already been created by the bicycle clubs. This included partial paths to Silver Heights and Elm Park and some blocks of Assiniboine Avenue, Broadway and Maryland Street.

In its first year, the Cycle Path Association raised about $1,400 from the sale of 2,000 tags and spent about the same on path repair and construction. Drewry was disappointed most of the city’s cyclists, estimated to be between 6,000 and 8,000, didn’t bother buying a tag.

Realizing that at $1,400 per year it would take decades to build the network he envisioned, at the association’s first meeting of 1900, Drewry suggested the purchase of bike tags be made mandatory for all cyclists. With that sort of income, he told the Manitoba Free Press, “I think we could do wonders towards making Winnipeg and the surrounding country an ideal wheeling ground. I don’t see why we could not have good cycle paths covering an area of 20 miles (32 kilometres) around the city.”

‘I think we coulddo wonderstowards making Winnipeg andthe surrounding country an ideal wheeling ground’– Frederick Drewry, president of the Cycle Path Association

The idea of a mandatory bike licence, or “bike tax” as it was often referred to, was a controversial one. Nonetheless, the Cycle Path Association pursued it with both the city and the province.

Civic officials, who would be the ones required to collect the tax and enforce compliance, were cool on the idea at first, and it was referred to numerous subcommittees over the summer for study.

The new legislation subcommittee of the provincial government seemed split until premier Rodmond Roblin weighed in and stopped it in its tracks. He called the tax an injustice to the poorer classes of people who used their bikes to get to and from work and that, “it was a flagrant monstrosity to charge them 50 cents each for the maintenance of paths to be used purely by the rich who had time to devote to such pleasures as pink teas in the park or garden parties in the suburbs.”

Drewry countered the opposition by stating the network would extend throughout the city, including industrial areas. Using Logan Avenue as an example, he said the inclusion of cycle paths there was necessary “so that the working man could go to his work on them… In twenty-five trips he could save, by (streetcar), fares the price of the tax.”

A debate that would not sound out of place in 2016 raged throughout the summer of 1900. Do cyclists deserve their own infrastructure? If so, who should pay for it — taxpayers in general or cyclists?

In the end, the city went along with the scheme and in April 1901 created the Cycle Path Board. Cyclists had to pay 50 cents for a numbered licence tag to be displayed on their bicycles, and the money raised would be earmarked for cycling infrastructure prioritized by a citizen board made up of members of the former Cycle Path Association’s executive.

With a licence bylaw in place, there was also the need for enforcement. Const. Warren Beggs of the park police was seconded to patrol the streets at paths to make sure cyclists had their tags. Thanks in part to his work, the number of tags sold rose to 6,000 in the board’s first year and peaked at 8,500 in 1905.

This increase in revenue, however, did not translate into much in the way of new cycle paths. The board started out with a network of roughly 13 kilometres of cycle paths in place, mostly along Portage Avenue to Silver Heights, an Osborne Street/Pembina Highway stretch to Elm Park, and one along Sherbrook Street north of Portage and Maryland south of Portage.

Five years later, there were only a few more kilometres to show for their work, mostly outside the city limits, thanks in large part to the city.

This was a time of great improvements in the city’s infrastructure. Streets were being properly laid out and subdivided, water and sewer pipes were being run and more telephone and electricity poles installed. Each time these improvements were carried out, entire blocks of existing bike paths could be wiped out. To avoid such disruptions, the Cycle Path Board requested the city free up a portion of all newly laid boulevards for cycle paths, but the city refused.

It was often left to Richard Waugh, secretary of the board, to defend their lack of progress.

In a lengthy interview with the Winnipeg Tribune in June 1906, he gave examples of sections of paths, such as on Portage between Toronto and Dominion streets, that had been torn out and rebuilt three times in three years. He aimed his frustration at the city’s engineering department.

❚ ❚ ❚

“As it is, they simply ignore the Cycle Paths Board, and as we never know the moment when our work on a street will be torn up, much of our labour is accordingly wasted.” He also noted, “it would require every cent of our revenue to keep the present paths in good condition without building any more.”

On Dec. 28, 1906, the Cycle Path Board, including Fred Drewry, met at the city hall office of Waugh.

They discussed what portions of paths had been destroyed that summer and would have to be rebuilt. One positive note about the new infrastructure projects was the city was going full force in converting its wood plank sidewalks to granolithic cement and asphalting road surfaces. These changes brought great benefits to cyclists trying to navigate around the city.

Realizing that as things stood their dream of a city-wide, and beyond, network of cycle paths would never be fulfilled, the board concluded the meeting with the following: “Resolved, that in the opinion of this board, present conditions do not justify the board in further continuing its organization and it hereby tenders its resignation as a body to the city council.”

Council accepted the board’s resignation, but there was one remnant of the organization it wasn’t about to give up. The mandatory licensing of bicycles, meant to raise money for the board’s infrastructure projects, remained in place until 1982.

Christian Cassidy writes about local history on his blog, West End Dumplings.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.