Pioneering Point

Strong-willed settlers' determined Peonan Point descendants finally got electricity in 1990, but the tiny community's 10 year-round residents are still off the grid in many ways

By: Bill Redekop Posted:Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/07/2017 (3087 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

PEONAN POINT — Oli Olson would get into his rowboat, pack his container of cream from his milk cows, and start to row Lake Manitoba.

The boat was handmade from spruce planks and oak ribs, materials found on Peonan Point where he’d settled in 1915. He’d row south along the west side of Peonan Point, a long peninsula that hangs down from Lake Manitoba’s north shore like a dagger.

But when Oli came around the tip and headed east towards the creamery at Steep Rock, he was never entirely sure what lake conditions awaited. Oli rowed into the open waters with tailwinds if he was lucky, into headwinds if he wasn’t, in rocky waves, choppy waves or, if God saw fit, a surface that was countertop-smooth.

And he rowed, and rowed and rowed.

“He was an old Icelander. They all know how to row,” says grandson Dave Olson, who lives on Peonan Point today.

Well, not exactly. He was from the Faroe Islands, about halfway between Iceland and Scotland. Close enough.

He rowed, and rowed and rowed because there was no other way into or out of Peonan Point; no road, no outboard motorboats, no hydro, no phones. Peonan Point wouldn’t get a completed road until almost the turn of the millennium. It was and still is, in many ways, a land time forgot, cut off from the rest of the world.

He rowed 30 kilometres one way, much of it in open water, but he often had company. He rowed and rowed with ducks flying up from shore, seagulls wheeling overhead, skeins of geese in military formation and probably a fish jump or two, curious to get a look at the crazy fellow in the boat.

He didn’t row his cream all the time — there was a cream boat that made pickups — but often enough.

He rowed until he finally crashed into the stony beaches of Steep Rock, crashed into two local history books and into these pages of the Winnipeg Free Press, into the moon and stars of legend whenever people talk about Peonan Point, and into the lore of untamed Manitoba.

Peonan Point. To many people in the Interlake, they are almost like magical words. I was told at least a dozen years ago that I needed to write about Peonan Point. People made it sound like some mythical place.

But there were certain logistics involved, and it required a significant investment of time. After all, it’s a story about a place where people have lived mostly in isolation for more than a century. A modern description might be “off the grid” except people have been living there about 10 times longer than that phrase has been popular, off the power and road grid.

Oli Olson is a good place to start Peonan Point’s history. Three of the four families who still live there year-round are his descendants. There were seven families, but three left after being flooded out in 2011 when the Portage Diversion added two feet to an already high Lake Manitoba. Another family, the Cooks, splits its time between Steep Rock and Peonan Point.

Oli wasn’t the only person living on the Point when he arrived. It was mostly settled by Icelanders but there were some English families, too. A logger named McPherson cleverly used a system of sails to float log booms from Peonan Point across Lake Manitoba. That must have been a sight.

Oli Olson immigrated to Canada in 1903, and worked as a farm helper, fisherman and on the steamship R.R. Spears hauling gypsum before settling at Asham Point on the southwest flank of Lake Manitoba.

His bride to be, Stina Indridadottir, arrived in Canada from Iceland a little earlier in 1902, reunited with her family, who had left her behind a decade before because Atlantic Ocean passage was dangerous for children. Portrait photos show her to be an attractive and serious woman, looking both proud and fragile at the same time.

Stina worked for six years in a sewing factory in Winnipeg, then followed a just-married friend to the Lake Manitoba Narrows in 1908 to work as a cook at a fish camp.

Oli and Stina met when he hauled his fish to the camp. Stina would have had her pick in the male-dominated camp and chose Oli. The handsome couple knew each other for only a short time before they wed in spring of 1909.

Stopping in Steep Rock on my way to Peonan Point, I met with four of their grandchildren. They spent their summers on Peonan Point but lived in Steep Rock the rest of the time so they could attend school.

Each summer, these grandchildren led the most deprived existence possible on Peonan Point: no radio, no TV, no candy, no refrigeration, no store, no cars, no modern toilets, no other friends except their cousins. And they had the happiest childhoods in the universe, they say in unison.

“If you were dirty, you swam in the lake,” Linda Nickel says of their carefree ways.

Their fathers were Karl and Kris Olson, the twin boys of Oli and Stina. As adults, Karl and Kris took turns managing the Peonan ranch in winter. One winter, Kris lived on the Point alone, tending the cattle and horses while Karl ice-fished and returned to Steep Rock with his catch each night. The next winter they reversed roles. Fishing and farming were their main livelihoods.

There seemed no evil in this Eden, the grandchildren said. “We didn’t know anybody was bad in the world,” says Karl’s daughter Margaret Snidal, 70.

“I never knew people would steal things from you, would take things that weren’t theirs,” adds Linda, 68, daughter of Kris.

Not that there was much to steal. Linda remembers having to share her one toy, a doll, with her sister.

“(Peonan Point) gave me….” she begins, then pauses to collect her thoughts. “It was almost spiritual. It was the sense of complete freedom and closeness to nature. We grew up really, really naive but I’m so thankful I had that experience and it was a wonderful way to start a life.”“We grew up really, really naive but I’m so thankful I had that experience and it was a wonderful way to start a life.”–Linda Nickel

It was a rocky start for their grandparents Oli and Stina, however. Oli arrived on Peonan Point by horse in winter of 1915 with the lake frozen over, picked a lush spot along the shoreline where he could watch the sunset each night and built a log cabin.

It may have seemed ominous that when he returned by boat in late summer to settle with his family— Stina, daughters Bina and Violet and the twin boys Karl and Kris — they found their home burned to the ground in a brush fire.

With winter approaching, Oli had to rebuild. After all, Peonan Point is nothing if not a story of self-reliance. It was like a reality series. Here’s the land. Here’s the water. Now live. But first, we’ll burn down your house just to add drama and boost ratings.

It seemed even more ominous when their horses made a getaway and swam back to Asham Point when the ice broke in spring. It was only when Oli brought them back and they foaled that the horses seemed to accept Peonan Point as their permanent home.

Peonan Point means “waiting place” in Cree. It drops down into Lake Manitoba from Highway 328, west of Gypsumville, about a four-hour drive northwest of Winnipeg.

The last hour or so is on gravel, and there’s just one lane.

The peninsula is 45 kilometres long and 6.5 kilometres at its widest point, narrowing as you travel south.

It’s mostly three kilometres wide, then two kilometres, then narrows down to a pencil-point. The road jogs east from time to time because Peonan Point angles from northwest to southeast like the rest of the topography here, including Lake Manitoba.

On the drive in I saw pastures and meadows, barbed-wire fences, Texas cattle gates, some water that was possibly an embayment of Lake Manitoba, mallards, sand pipers, red-winged blackbirds, a blue heron that flew up with its long legs dangling underneath like a clothesline, oak trees, poplars, birds perched on fenceposts, water in ditches, reddish-brown cows with white patches on their faces, dandelions in their afro-headed seeding stage and bulrushes, scores of last year’s bulrushes turned cottony white.

“Fields of bulrushes, like an unharvested crop,” I scribbled into a notebook.

When I show up at Dave and Phylis Olson’s home — where I stay during my visit — Dave is in front of the open garage pouring ammonia nitrate fertilizer into empty two-litre pop bottles. Ammonia fertilizer, in its granular form, is a pretty, orangey-pink colour. You add diesel fuel and a detonator — only obtainable with a special licence, which Dave has — and you have an explosive. Dave is making bombs to blow up beaver dams.

He stands back about 100 metres when he detonates because stones, rocks and sticks are launched by the explosions.

“You don’t want that stuff to rain down on your head,” he says.

Beavers. Bulrushes. I was starting to see the connection.

Beavers moved in with the floodwaters of 2011. When the water receded, the beavers were stuck. A beaver out of water is defenceless prey. So the beavers went to work plugging culverts like mad, flooding the land. Local men removed 90 beavers in just one kilometre-long stretch alone last year.

Dave has lived his entire life on the Point except for a hiatus between 1979 and 1985. “Five o’clock rush hour doesn’t bother me too much,” he says.

True. You could drive the length of the Point road and not see another vehicle. That’s the norm. You might have to wait a couple days for help if your vehicle breaks down. Cellphones read “no service.”

Wolves were among the many challenges faced by his grandparents Oli and Stina raising cattle and horses on the Point, he says.

So Oli became a wolf hunter for hire in addition to ranching and commercial fishing. Oli purchased a team of wolfhounds, possibly the Russian variety — like greyhounds but heavier. They couldn’t kill a wolf but would chase and corner it so Oli could finish it off.

In those days they rounded up cattle on horseback. To get to market, ranchers on Peonan Point herded long cattle drive on horseback all the way to the community of St. Martin, a distance of up to 80 kilometres. That continued until 1956, when someone obtained a motorized barge to move the cattle to Steep Rock.

Oli also moved into raising sheep because they were smaller than cattle. The family could consume a sheep before the meat went rancid. Stina knit the wool into clothing.

One of Dave’s memories growing up is of getting meat from their “refrigerator.” They didn’t have one, of course. So they used the bottom of the well where it was cool. They stuck a culvert just over a metre wide down their well and would hang food from a string down to the lower reaches. They would then hook the string around a nail in the well’s crib. The food included sealers of meat from a sheep or deer.

How many strings did they hang? I ask, expecting the number to be three or four. “About 25,” Dave says. “Anything you’d put in a fridge today you hung down the well.”

His grandparents did whatever it took to survive. From the 1920s to the 1940s, Stina sold meals to fish camps. Their place became a stopover for fish camps, comprised of up to 20 fishers en route from the west side of Lake Manitoba to deliver fish to Steep Rock. They travelled on the ice in horse-drawn cabooses, heated inside with wood stoves.

Dave has also been a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. He’s dabbled in cattle farming but has been primarily a commercial fisherman. He also does guiding — and blows up the beaver dams. He’s semi-retired but is involved in the construction field with his sons.

Like others on Peonan Point, Dave and Phyllis live isolated and in wilderness but they also live on a five-star beachfront, or it would be if it was sand instead of the smoothed skipping stones along Lake Manitoba.

Most of the houses on Peonan Point are on small points where the lake wraps around their huge yards on three sides like a horseshoe.

Their home is about halfway down the Point, compared to most houses, which are farther south. Dave built their log house himself in stages, starting in 1985, before there was electricity.

He used poplar logs that a logging expert from Sweden told him could last 300 years. They don’t crack like spruce or twist like pine, he says. The logs were freighted over frozen Lake Manitoba.

It’s a gorgeous home, and solid as a rock.

The first generations on Peonan Point were Swiss Family Robinsons living in wilderness.

The town of Steep Rock was nearly 100 kilometres distant by land, although only 10 kilometres by water or ice from the nearest point.

Families on Peonan visited each other regularly, and there were well-worn horse trails between the residences. There was a two-way radio service in case of an emergency. But there was no hydroelectric power.

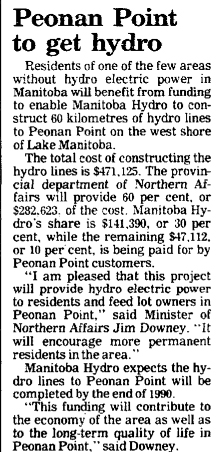

Peonan Point was the last rural community in Manitoba to get electrification, Manitoba Hydro records show.

There were some crude precursors. In 1930, Oli purchased a 32-volt wind charger and battery pack to provide electricity. This was like a wind turbine. Electricity had arrived, albeit in a very rationed form.

Diesel generators were eventually adopted in the 1950s and ’60s, and propane refrigerators followed. The generators provided only enough electricity for lights and pumps on the feedlots. Without electricity, there was never any reason for kids to be inside the house except to eat and sleep, Linda says. However, she remembers reading from light provided by a diesel generator. When her father cut the generator at night, she would have to hurry to finish what she was reading before the generator wheel came to a complete stop; it took a couple of minutes.

Manitoba’s first rural electrification program ran began in 1921 but primarily serviced southern Manitoba. The last go-round for the formal program included the east side of Lake Manitoba. In 1950, the village of Steep Rock got electricity for 47 households. Peonan Point wasn’t considered.

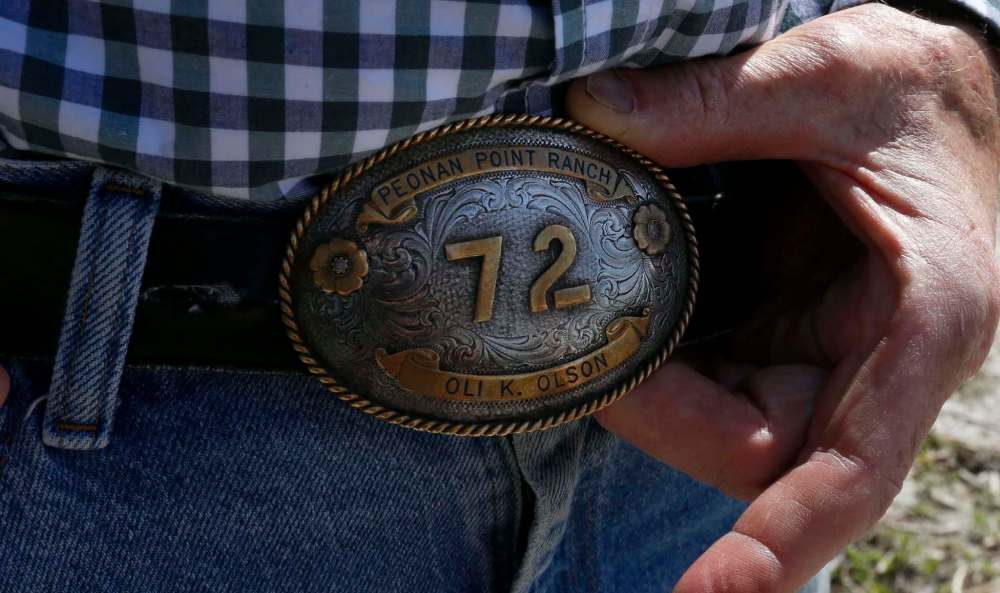

Oli’s grandson Oli Kristin Olson made it his personal mission to obtain electrification for the Point. Oli Kristin was mayor of Homebrook-Peonan Point, a jurisdiction under Northern Affairs, for 26 years.

There is a story told in an Olson family history book about then-Manitoba premier Gary Filmon reacting with outrage when he learned there was still a community in the hyrdoelectricity-rich province without electricity and issued an order to rectify the situation.

That story has never been verified. But the government wasn’t shy about letting it be known it was going to hook up the remote community. Then-Northern Affairs minister Jim Downey — Filmon’s deputy premier at the time — made the long trek out to Peonan Point for the official switching on of power, including riding horseback part way.

That stemmed from a practical joke Oli Kristin and his girlfriend Anne Campbell cooked up. Anne rode out to meet the minister, trailing a spare horse behind her, and told Downey the road was impassible and he would have to ride the last 500 metres. The ceremony and a barbecue awaited.

But Downey, from a farm background, was undaunted. “You guys think I’m not up to this, eh?” he said, and surprised everyone waiting for him when he got to the destination via a single horsepower.

“I thought he was a good sport about it,” Oli Kristin says.

A Manitoba Hydro employee’s recollections about constructing the 60-kilometre line are recorded in the utility’s archives. Area residents helped clear the route. During down time, hydro employees played hockey against residents on a frozen pond.

“I do know that when we turned (the power) on, people had made up signs on white bedsheets saying, ‘Thank you Manitoba Hydro,’ and had them on their houses when we came to put the meters in,” he said. “It was actually quite an experience both for myself and others to see these people just getting power in 1990.”

The funding agreement to electrify Peonan Point came to $471,000 and was split three ways. Manitoba Hydro paid $140,000, Northern Affairs $282,600. Residents paid $47,000 — 10 per cent — and helped clear bush for the line. That was for 16 service connections, most of them seasonal residents.

Oli Kristin was one of the year-round residents. Born in 1950, he has lived his entire life on Oli and Stina’s homestead. The old house is still intact; additions have been built on either side. “This is my grandma’s kitchen,” he says, as we sit, drinking coffee.

The houses on Peonan Point were heated with wood pre-1990. It meant harvesting mountains of firewood each fall and winter. “I used to saw all the wood… but once hydro came I haven’t burned another stick,” he says.

Anne was interviewed on national radio by CBC Radio’s Michael Enright while the line was under construction. Towards the end of their chat, he asked her about telephone service. She told him Manitoba Telephone System had agreed to provide service… at a cost of $14,000 per household. Enright almost spit out his coffee. “Fourteen thou!” he exclaimed.

Of course, residents didn’t go for that.

It’s hard to imagine a community without a road. Peonan Point made do with trails like the early pioneers did.

Having no roads complicated life in myriad ways.

Expectant mothers couldn’t risk waiting until labour was imminent; they had to get to Ashern — the better part of two hours away — when its hospital still did deliveries, or Winnipeg with plenty of time to spare.

And if it was spring, departure time was before the ice broke, not when the woman’s water broke, even if the delivery date was more than a month away.

Farm equipment and building materials had to be delivered in winter when the lake iced over. There was also more of a social life between Steep Rock and Peonan Point in winter because the frozen lake permitted travel.

By the time electrification came in, there was a partial road, but it quit about halfway down, some eight kilometres from Oli Kristin’s place. He couldn’t wait any longer, so he bought a grader and extended the road himself. That was the path Downey and his equine transportation took to get to the festivities.

“The general public didn’t get here. There was no road so it wasn’t attractive,” Oli Kristin says.

But Manitoba Hydro was in their corner now because it wanted the road to service its line. That may have given the province the final push to continue the road.

The road was completed in either 1993 or ’94, he says. Life changed again for Peonan.

Oli Kristin mostly saw the advantages from the business perspective. Before the road existed, cattle had to be marketed in the fall, when the land was dry.

“By that time the price was usually half of what it was earlier,” he says. “It made a dramatic difference in marketing.”

Otherwise, he didn’t see it as such a big deal.

“When we first got the road, I would go to Steep Rock (90 minutes away) three or four times a week, but that got old pretty quick,” he says.

When I ask other people about the road’s impact, they mostly speak in the negative, as if Peonan Point lost more than it gained.

To the outsider, the hamlet still seems very isolated. But to people who live there, it’s as though the road turned Peonan Point into a suburb. Perhaps they have just become so accustomed to having the road that they can’t remember the hardship of life without it.

“I became a better public servant,” Oli Kristin says, prompted to say something positive. He meant that as mayor, he could finally attend Homebrook-Peonan Point council meetings. He also served as director of the Interlake Cattle Co-op, the Interlake Livestock Forage Improvement Association and the Manitoba Hereford Association.

Yet others wax nostalgic for life before the road. “I guess it just made us like the rest of the world,” says Dave Olson. He tells a joke about Davy Crockett saying it was time to move when you could see chimney smoke 10 miles away.

Linda Nickel is more emphatic. “With that road, Peonan Point lost its innocence,” she says.

Why did people stay? Why didn’t they move somewhere more accessible?

The truth is, people there did very well financially. Some of the biggest ranches in the province were on Peonan Point. The reason for that is its native grasses are excellent for raising cattle, second to none in Manitoba.

“Prior to the flooding (that started in 2011), this was foolproof cattle paradise,” Oli Kristin says.

You didn’t have to clear land and you didn’t have to improve your pastures by seeding alfalfa. You just moved your cattle from one pasture to the next.

“It’s pretty much entirely native grass. When I was younger in the 1960s, we had so much pasture we were running 600 cows” when most cattlemen had less than a third of that, he adds.

The Olson clan together at one point leased about 40,000 acres and had 2,500 head.

“Native hay land and grasses will sustain livestock, and we proved it here. We’re getting into the fifth generation raising cattle on native pastures,” he says, adding his son Eric also runs cattle farther south on the Point.

Today, Oli has 21,000 acres, most of it leased. Eric has about 5,000 acres, but 4,000 of them have been under water since 2011. He owns about 640 acres and the rest is leased Crown land. All the farmers on Peonan have similar arrangements.

The family’s herd has shrunk to just 600 from about 1,100 before the flood.

Betty Konzelman, who retired from teaching in the early 2000s, was the community’s first teacher in the public “school” that opened in 1990.

“It was almost like going back in time,” she says.

She had five students, all children of Dave and Phyllis Olson. Their schoolhouse was an old fish shack on the Olson yard. Konzelman had been a long-time friend of the family and still is. “I’d known the children since they were babies.”

She recalls one incident that wouldn’t happen in a public school today. A coyote was hanging around the yard one day and she and the kids felt trapped inside, afraid to use the outhouse. So one of the boys climbed out the back window and ran to the house to get a rifle. He came out blasting into the air until the coyote ran off.

Nothing wilder than a cat named Smokey, and his feline pal Bacardi (yes, like the rum), has threatened to disrupt classes lately. The cats are one sign the school is less formal than most. From time to time they’ll bound across the floor in pursuit of a pencil or something else they can bat around.

Peonan Point School offers Grades 1-12 but there were only six students during the past year; one in Grade 5, two in Grade 8 and one each in grades 10, 11 and 12.

Phyllis Olson was instrumental in establishing the school in 1990.

She home-schooled her kids when the family moved back to Peonan Point in 1985. The youngest of their five children was two years old and the oldest was in Grade 6. But when her youngest came of school age, she panicked at the thought she might fail to teach him to read and petitioned the authorities.

“I got hold of Frontier School Division and said, ‘I have five kids and they need to be educated. I have a building you could use.’ (The superintendent) was in total agreement. They sent painters in to paint the building. I had a friend (Konzelman) who agreed to be the tutor.” The school ran from 1990 to 2000 in their yard for their kids initially, and later some cousins, too.

But the school never had a student population of more than half a dozen or so until 2000, when four families from Alberta moved to the Point with a passel of children. The school was moved to Arvid and Debbie Nottveit’s house near the southern point until a proper school was built in 2001-02. At the time, the “Nottveit” school was bursting at the seams with 19 kids. The school built to accommodate the population explosion is, essentially, a one-room facility, but there are some smaller spaces for workshops and a storage area.

Three families, two with school-age children, left after the 2011 flood. So it’s back to a half-dozen students again.

Two of the six don’t even live in Peonan Point. One arrives from Steep Rock (which hasn’t had a school for years) either by snowmobile or boat, depending on the season. Another is from Fairford and stays with her grandparents, who live on the Point. She will usually start her week at school but then works from home on assignments later in the week. The student from Steep Rock also works from home when neither boat or snowmobile travel is practical.

It’s a case of school of choice. Otherwise, she would have to be bused to Moosehorn, just north of Ashern — a significant distance from the Point.

“It’s a very fluid system,” says current principal-teacher-janitor, Maggie Macdonnell.

There are fewer than a dozen year-round residents; the number can swell by a handful if university-age kids return for the summer.

Despite the small student body, the future of the school hasn’t come up for discussion. “What would you do? Are you going to run a bus (from Peonan Point) to transport students to a school at least an hour away?” she asks.

After all, that’s the mandate of Frontier School Division. It deals with isolated and long-distance education from Falcon Beach in Whiteshell Provincial Park to Churchill on Hudson Bay.

Macdonnell, like Konzelman, says she’s found her dream job late in her career.

“I love it. It is the best job in the world,” she says.

During the week, Macdonnell lives in a little house next to the school called a “teacherage.” It’s an upgrade from what predecessor Konzelman had. She stayed in “a little shack not much bigger than a kitchen table,” she says.

Macdonnell likes to knit and sew and that’s what she does after work. Her house resembles a “craft room.” During and after ice breakup, she hops behind the wheel of her vehicle and heads to her Steep Rock-area home for the weekend. In the winter, the makes the trip there and back in a Polaris Ranger all-terrain vehicle with an enclosed cab and caterpillar tracks that get her over the frozen lake.

“I’m teaching 100 per cent of the time. I’m not spending time disciplining. It’s like stepping back in time. The students are respectful, want to learn and are like little sponges,” she says.

And the children “have strong work ethics,” she says.“When chewing your fingernails and daydreaming are the worst things the kids do, it’s not too bad,”–Betty Konzelman, retired teacher

“They don’t have access to all the media stuff, living in an isolated area.”

When they’re not in school, the kids get together to play board games and card games and clear the snow off the lake ice to skate, she says.

They take school field trips. This year they travelled for about a week to the Royal Tyrrell Museum of palaeontology in Drumheller, Alta., as well as the RCMP Museum in Regina and a few other stops along the way.

“It’s an answer to my prayers,” Susan Olson says of the school.

One challenge is the lack of peers for her son, Owen, heading into Grade 6 next year. They try to make up for it in various ways. On the plus side, the students get one-on-one attention, and they each have their own computer.

This year the kids sewed a quilt and made their own school jackets with the Peonan Point logo, a puma. They started a greenhouse and grew peas, beans, lettuce, potatoes, rhubarb, beets and radishes. They sell the seedlings around Peonan Point.

Discipline is not — ever — an issue.

“When chewing your fingernails and daydreaming are the worst things the kids do, it’s not too bad,” Konzelman says.

One side-effect of there being so few kids is families stay close.

“You had no other friends to play with (other than siblings). So you had to say ‘sorry’ if you wanted to play some more,” says Eric Nottveit, 22, while visiting with his parents, Arvid and Debbie.

It was the same with Dave and Phyllis Olson’s children.

“With our kids, they got to be each other’s best friends because that’s all they had,” Phyllis says. Today, their three sons are in business together.

Does Eric remember the isolation growing up? “You don’t really know it as a kid. That’s just the way it was,” he says.

His parents noticed it by the number of times they would load up the sleigh with his hockey gear and snowmobile across the frozen lake to Steep Rock, where they kept a truck. Then they would drive another hour or so to hockey games.

Many times they returned and crossed the lake in the middle of the night. There are stakes marking a route across the ice. The family rule was if it was snowing or blowing so hard you couldn’t see at least two stakes in front of you, you didn’t cross. You either stayed at home or on the other side of the lake.

Phone lines arrived shortly after hydroelectricity. Government found a way to offset some costs so residents could get individual telephone towers on their property for a couple of thousand dollars. They are actually two-way FM radios. The towers send microwave signals across the lake to a tower in Steep Rock. That’s how they get their internet, as well.

The phone line is trained across the lake but the phone and internet are frequently down because the signal often bounces off the water or ice.

That has mitigated the isolation to some extent, but Peonan Point lifestyle hasn’t changed much.

“If you’re an outdoors person, you’re just a lot more at home when there aren’t a lot of people around,” Oli Kristin says.

Writers, too. One can’t help but think this would be about the best place in the world to write a book, any kind of book. Nature, walks, alone with your thoughts, where every human encounter, no matter how brief or inconsequential, takes on deeper and mysterious meaning.

Visitors are frequently amazed.

“We’ve had church picnics in the yard, and people will say, ‘We didn’t know places like this existed anymore,’” says Arvid Nottveit. A 60- to 90-minute drive awaits families who want to attend church services in surrounding communities.

Satellite television has been around for a long time but two of the four permanent families choose not to watch TV, although the Nottveits stream Netflix.

But social isolation has not been easy for some people, particularly female partners. “I’ve been married a couple times and most of the time we got along pretty good, but they wanted a social life,” Oli Kristin says.

“I think (the isolation) was hard on women. It’s really lonely,” Phyllis agrees, talking about the past and present. “It was a great place to raise kids,” she says, but now that they’re grown, loneliness has become a factor.

“I’m kind of social. Sometimes it’s too far to go into town. I’m 60 and sometimes the solitude is awful,” she says.

Neighbours take on greater importance. “I’ve been in everyone’s house on Peonan Point, and they’ve all been in our house,” Arvid says. “We feel very blessed to have such good neighbours.”

Arvid participated in a telephone survey recently and was asked whether he felt safe in his home.

“I said, ‘Safe from what? Bears? Wolves?’” He says life at Peonan Point is such that he’ll “come home and my truck will be gone because a neighbour needed to borrow it.”

As for the rest of the world, he says, “sometimes it’s a long ways away and sometimes it’s not far enough away.”

A flood of frustration, weary of the bul… rushes

In 2011, Arvid Nottveit was one of the unforgettable faces of the Lake Manitoba flood. The desperation written on his face at flood meetings in the Interlake.

He had 600 cattle and had to get them off Peonan Point or they would drown. The lake was rising because of naturally high waters, but also because the Portage Diversion was flushing record volumes of water into it.

It was eventually determined the diversion raised the lake level by two feet that summer.

All the Peonan Point farmers were affected, but Nottveit’s land was the lowest and his cattle had nowhere to go. The road into the Point had been flooded out. So he had to move the animals by barge.

That’s not a simple task. Just getting a barge into Lake Manitoba’s northern basin was an ordeal. The only one available was south of the Narrows and its wheelhouse was too tall, and the lake level too high, for it to fit under the Narrows bridge. So the wheelhouse was removed, carried over to the north side of the bridge and then reinstalled.

Neither is it just a simple matter of herding cattle onto the barge. Cattle have to be paired up — mother with calf — or the separated young will die.

“Nothing was easy,” Nottveit says.

More than 90 people helped him with the evacuation, and most had to take time away from their own jobs. He moved out 430 of his 600 cattle. His family couldn’t return for two years. Their home was an island of five acres surrounded by water.

So they rented a boarding house in Steep Rock. He obtained feed for his animals wherever he could. “I made hay on 14 different farms,” he says.

Today, his fields — normally delicious native grass for his cows — have been transformed; where there were once hay bales dotting the pasture, there are fields of bulrushes.

There’s little Nottveit can do until the land dries. The lake operating range is 810.5 to 812.5 feet above sea level. It hasn’t been inside that range since before the flood. It is 813.5 feet when I visit.

The land never dries up because it can’t drain when the lake is higher than the land, Nottveit explains.

“It started improving, then flooded again in 2014. Now we’re high again in 2017 (because of heavy snowpack in Saskatchewan last winter and Portage Diversion drainage). We need a couple of dry years.”

He can cut the bulrushes, but all it’s good for is bedding for cattle when they’re birthing. The trouble with government crop insurance is it covers only a single year and native pasture takes several years to recover. It’s not like the Red River Valley, where fields flood and producers are seeding crops on them a month later.

The Interlake is paying for the uncompleted flood mitigation network. That is, Lake Manitoba doesn’t have a proper outlet channel.

The outlet channel was supposed to be part of the province’s flood mitigation network built after the Red River flooded Winnipeg in 1950. The province built the Winnipeg Floodway, the Shellmouth Dam on the upper Assiniboine River, and the Portage Diversion on the lower Assiniboine into Lake Manitoba. But the government commitment ran out of steam before completing the last phase: an outlet channel from the lake to move away additional waters from the Portage Diversion.

As a result, people along Lake Manitoba have been flooded about every second year since 2011. The only outlet, the Fairford River, is able to carry only a small fraction of the water being redirected by the diversion.

So the hackle hairs go up when people on Peonan hear others claim they live on a floodplain and should expect flooding. Peonan Point is 100 feet higher than James Richardson International Airport, says Dave Olson.

“You’re the ones on the floodplain backing up water into here,” he says.

The previous NDP government built a $100-million emergency channel in 2011 to transport water from Lake St. Martin to the Dauphin River and into Lake Winnipeg. But that still doesn’t address Lake Manitoba’s problem.

In fact, the emergency channel will be mothballed. It is being abandoned for “environmental” reasons, the province says. The operation of the emergency channel cause scouring and erosion of Big Buffalo Lake Bog and Buffalo Creek. It has also wiped out walleye spawning in three of the last six years on the Dauphin River and Buffalo Creek. That has devastated fishing for Indigenous commercial fish harvesters in Sturgeon Bay on Lake Winnipeg.

“The emergency channel will be repurposed for environmental support purposes, which are still being defined and developed,” a provincial spokesman says.

Derek Johnson, Progressive Conservative MLA for the Interlake, refrained from taking potshots at the NDP for the emergency channel’s shortcomings. “They did what they thought was right, and what they thought was right was lowering Lake St. Martin,” he says. Now a new emergency channel will be dug to Lake Winnipeg.

But Johnson also reaffirmed Manitoba’s commitment to dig an outlet channel from Lake Manitoba to Lake St. Martin, too.

“We’ve been hard at work engineering and designing that channel,” Johnson says. “There is going to be a complete project that goes from Lake Manitoba through to Lake Winnipeg.”

“It will be part of the permanent channel operation,” meaning at long last the final leg of flood control that includes the floodway, Shellmouth Dam and Portage Diversion, will be completed, he says.

It’s something every government so far has failed to do. The total cost of the two channels is estimated at about $500 million. Federal and provincial governments are cost-sharing the expense. Negotiations with some First Nations are also involved. Construction is now likely to start on both in 2019, the province says, with completion possible before 2024.

Having been disappointed by so many governments before, seeing will be believing for people around Peonan Point and the rest of Lake Manitoba.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca