Korean sensation in spotlight

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/03/2018 (2755 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

NORTH BAY, Ont. — When EunJung Kim strode off the ice Wednesday afternoon, reporters began to hover like moths to a flame. She’d just lost to Canada’s Jennifer Jones, but this is what the Olympics does to people: it gives a glow.

For a moment, the 27-year-old South Korean skip hesitated at the attention. She was waiting for her coach, MinJung Kim, who often serves as translator. But the coach wasn’t yet in the back hallway of the arena.

Instead, the skip looked over to a huddle of fans, waiting behind a nearby crowd-control barrier.

“She is a translator,” Kim said, and gestured towards a young woman in the middle.

As Vanessa Lee stepped into the media scrum, she looked surprised. She wasn’t expecting to wind up in the heart of the action; she’d come to these world championships from Toronto as a fan with a group of friends.

Now, she was helping to share Kim’s words with the media throng, recounting shots and ends. She was good at it; by the end of the interview, a Curling Canada official had enlisted Lee to serve the whole week as translator.

“Like, pinch me,” Lee said later. “It’s crazy. I cancelled all my plans this weekend and booked an Airbnb.”

It was a very curling moment, one of those collisions of elite play and everyday life that seem to happen in this sport more than any other. It was also a sign of how high this team’s star has risen since their silver-medal performance at the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics.

Just look around North Bay. All week, Korean fans have filled the arena, raising the nation’s Taegukgi flag in a sea of Maple Leafs. They’ve brought gifts for the team, including tulips and care packages of Korean snacks.

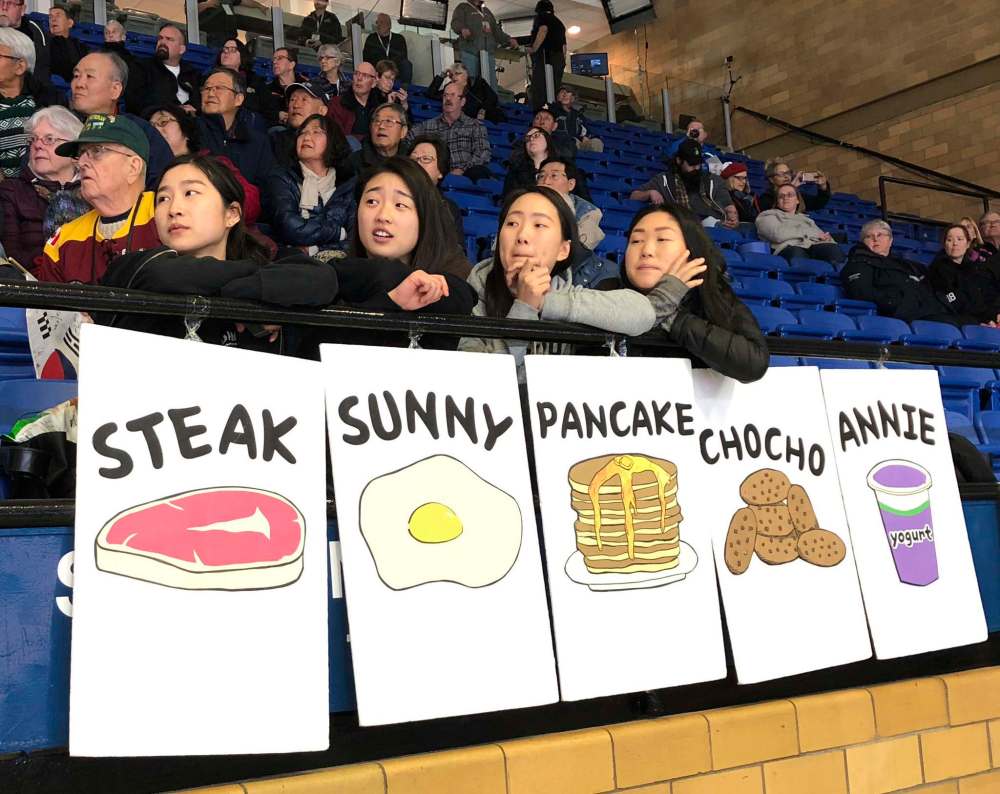

Lee and her friends made brightly coloured signs: one side reads “Curling Avengers” in Korean Hangul (Korean alphabet). As Korea pushed into the top third of the round-robin standings, fans cheered every hit, every point, every draw.

That sound is music to the team’s ears. They became overnight superstars in Korea after capturing Olympic silver on home ice in February. Now, they are finding out how that celebration stretches clear across the Pacific Ocean.

“Coming here, what we didn’t expect was to have a lot of support,” skip Kim said, with Lee translating. “Having Koreans coming here is so touching for us, and just a real surprise.”

They haven’t dominated the round robin in North Bay, as they did in Pyeongchang. After Thursday’s games, Korea was sitting at 7-3 and has qualified for Saturday morning’s playoff qulaification games.

Yet the team, which includes sisters KyeongAe Kim at third and YeongMi Kim at lead, as well as second SeonYeong Kim, have earned some of the most buzz here, eclipsed only by the icons on Jennifer Jones’ Canada squad.

It was the Olympics that did it. Their silver run made them sensations, as did the skip’s laser-focused game face. They get recognized on the street, now; photos of the team sparked anime caricatures and internet memes.

Or, as a Buzzfeed headline proclaimed: “People Are Obsessed With This Adorably Serious Olympic Curler.”

There were nicknames. Korean fans dubbed them the Garlic Girls, a nod to their hometown Uiesong’s most famed agricultural product. The skip’s bold round frames earned her the fond moniker of Glasses Sister.

And in Toronto, Lee and her friends were entranced. Lee had been a casual curling fan, before all of this — “I fall in love with curling whenever the Olympics are on,” she said — but this team’s spirit and backstory drew her in.

Once, Lee trained in archery close to Uiesong, a farming community about 200 kilometres southeast of Seoul and, now, the heart of Korean curling. So the team’s regional accents were warmly familiar; they connected.

“As soon as I heard them shouting that dialect on the ice, I fell in love,” she said. “They were so much fun to watch.”

What a rise, for these four women. During the Olympics, the BBC called the team “accidental superstars,” but their trajectory was far from accidental: Korean curling has been working towards this moment for decades.

In a twist of fate, that work began in North Bay. It was here that, in 1997, a Uiesong teacher named Kyung-doo Kim — coach MinJung’s father — brought a group of students hoping to learn the finer points of the game.

At first, the manager of North Bay’s curling club thought the calls from Korea were a hoax, he told a local paper this month. But that visit would solidify Kyung-doo Kim’s dream: to transform Korea into a curling nation.

Like many young national programs, the Koreans reached out to Canadians for help. By the late 1990s, they’d recruited Elaine Dagg-Jackson and her husband, Glen Jackson, with a mission: they wanted to get good, fast.

Dagg-Jackson, now the Canadian national coach, made her first visit to Korea around 2001. At the time, there were no dedicated curling facilities, only hockey areas with sheets laid down; they worked with what they had.

“They asked us to put together the best curlers in Korea, so they’d all come and try out,” she recalls. “You were just looking for people with the right attitude, and athletes who could pick things up quickly, technically.”

To fill up rosters, coaches would coax young athletes from other sports, including gymnastics: the agility and balance, they found, transferred well to the ice. Before matches, curlers would warm up with tumbling flips.

“That was a hoot for me,” Dagg-Jackson says. “It was a very modest curling community, but like any new curling community, once they catch the bug and see how wonderful the sport of curling is, they were all-in.”

Soon, that foundational work paid off. In the mid-2000s, EunJung Kim was entering high school in Uiesong. She learned the sport in gym class; within years, she’d won three straight silver medals at the Pacific-Asia juniors.

By 2014, the young skip began to realize she was ready for the next level. She captured her second Korean women’s championship that year, and with support from sport organizations, struck out across the ocean.

Over the next years, the squad schlepped across Canada, throwing rocks in work-a-day prairie bonspiels. It wasn’t glamourous, but they were going toe-to-toe with the world’s best and, often, they were winning.

In 2015, they upset Jones to win the Canad Inns Women’s Classic in Portage la Prairie, the first non-Canadian team to do so. They made their grand slam debut that year, and began pushing to tiebreakers and semifinals.

So there’s a certain symmetry in coming back to Canada as Olympic finalists: “I’m really happy that (worlds) could be in a city like North Bay,” the skip said. “Every time we have a good experience in Canada.”

Only now, they are not just another team slugging it out on the circuit: they are Korean legends in the making.

“It just means a lot, seeing how curling has become a well-known sport now in Korea,” coach MinJung Kim said. “We’ve gone through a lot of difficulties along the way, and we’ve had to overcome those difficulties.

“We’re finally reaping the results, so seeing that in the future will be really rewarding.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.