Cartoon party

While technology has allowed animation artists to work independently in their own spaces, many filmmakers thriving here point to Winnipeg's knowledgeable, supportive creative community for boosting their careers

By: Jen Zoratti

Posted:

Last Modified: | Updates

By: Jen Zoratti

Posted:

Last Modified: | Updates

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/04/2018 (2724 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

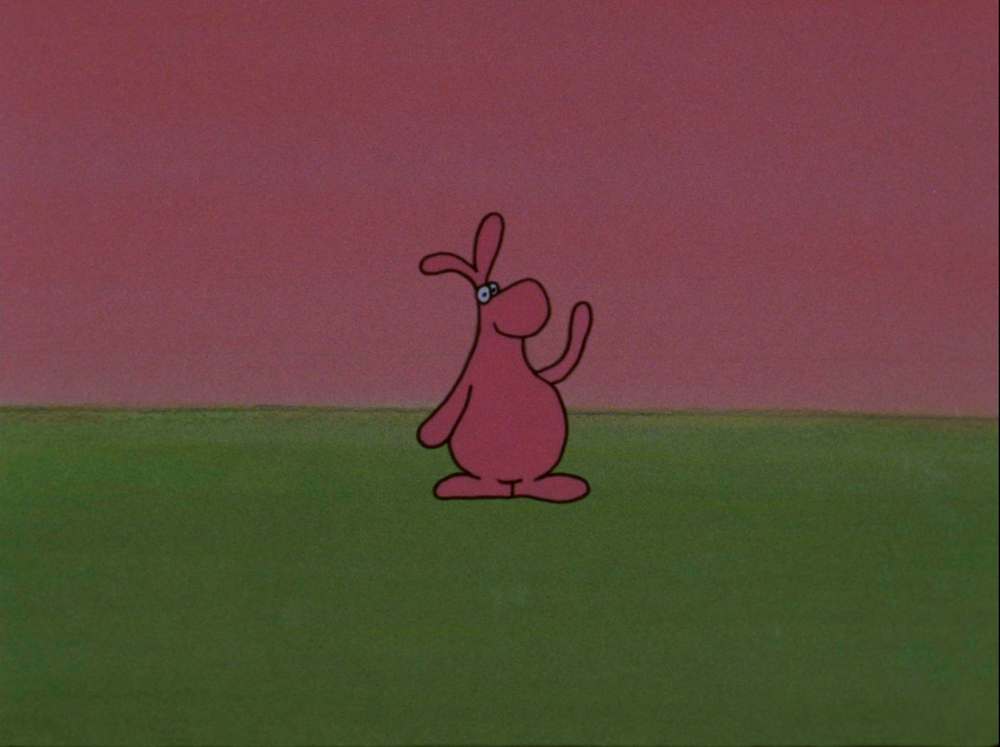

In 1985, Winnipeg animator Richard Condie released a short film called The Big Snit.

The offbeat 10-minute comedy — about a Scrabble game, marriage, nuclear war and a reality-TV precursor called Sawing for Teens — went on to become one of the most influential works in animation. Nominated for an Academy Award and a host of other accolades, The Big Snit is a product of Winnipeg’s National Film Board-produced animation heyday, along with Brad Caslor’s Get a Job (1985) and Cordell Barker’s The Cat Came Back (1988).sid

But Winnipeg’s rich animation tradition didn’t end in the ’80s. A new generation of independent animators are telling funny and poignant stories in bold, innovative ways. In bedrooms, basements, and rented studios all over town, these artists — too many to mention in the space of this piece — spend hours, sometimes hundreds of hours, painstakingly creating whole worlds using a medium that, to a viewer, feels close to magic.

Here, we look at some of the players in Winnipeg’s independent animation scene who are being recognized nationally and internationally — and the influence this city has on their work.

During a lull in the conversation at an Easter family gathering some years back, Alain Delannoy’s nephew asked a question that one wouldn’t exactly file under topics for dinner-table discussion. The actual question will not be published in order to protect the asker’s rep in the schoolyard.

“But my brother-in-law leaned over and said, ‘I think it’s time for The Talk,’ into my ear,” Delannoy recalls. “I thought that was kind of funny, and I shared it with some friends, and they were all laughing because they were like, ‘I do not envy your nephew or your brother-in-law, because that was the worst, most uncomfortable thing.”

They all started to share their talks. “And something hit me,” he says. “I told them to all shut up; ‘I have an idea, would you share these stories with me?’”

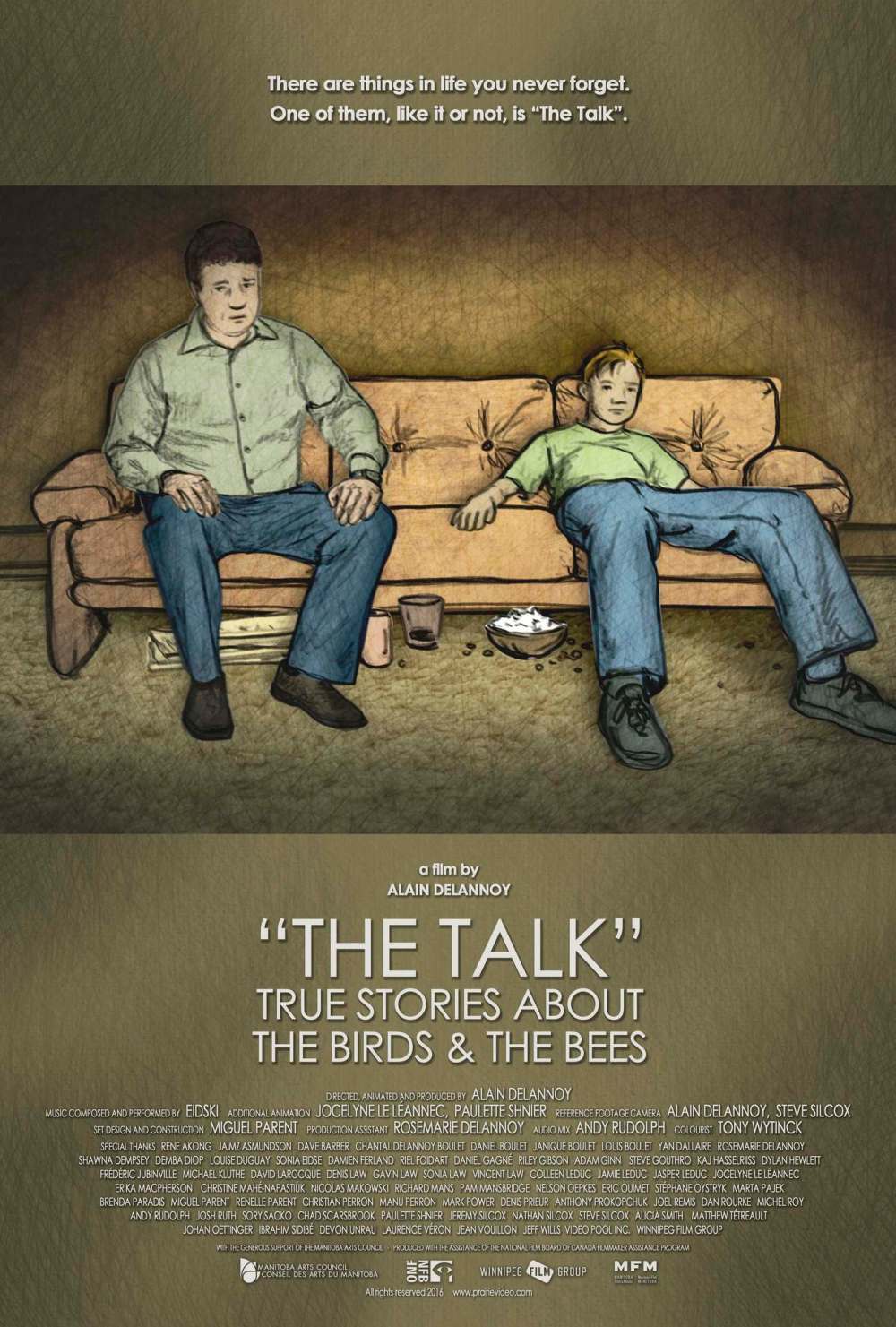

The result is Delannoy’s latest animated short, The Talk: True Stories About The Birds & The Bees (2016). Using the recordings from interviews with eight men, Delannoy employed a variety of techniques — including hand-drawn animation and rotoscoping, which involves tracing over motion film footage frame by frame — to bring their awkward and hilarious recollections to life. (The Talk will be screening at Winnipeg’s Cinematheque May 2-16, playing with the full-length documentary Ask the Sexpert. It will also première on CBC June 7 at 11:30 p.m.)

The film hit on a simple truth: everyone has had The Talk and experienced the veritable rainbow of mortification that comes along with it. (For the record, Delannoy was eight. It came via his cousin, who used a rather utilitarian tap-and-sink metaphor. “Our parents were tradesmen, so it totally makes sense.”)

The Talk has been a hit on the festival circuit. Since it made its world première at the Rhode Island International Film Festival in 2016, the film has screened at dozens of prestigious festivals all over the world including, most recently, at the 2018 Doc Fortnight at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

The Talk was also one of the 63 films that qualified in the animated short film category at this year’s Academy Awards, along with Winnipeg expat Matthew Rankin’s The Tesla World Light.

“It was a pleasant surprise,” Delannoy, 43, says of the film’s reception. “Trust me, I’ve gotten a lot of rejection letters in the past.”

He started working on The Talk, which is just shy of nine minutes, in the summer of 2013 and completed it in April 2016. He worked on it almost full time between September 2014 and February 2016 while juggling his day job as a multimedia instructor at the Université de Saint-Boniface. “I was on edge after that… that’s a long stretch,” he says.

Still, it was a labour of love. “I really, really enjoyed working on this project, and it played a lot of documentary film festivals, which kind of blew my mind,” he says. This was Delannoy’s first foray into making an animated documentary short, a genre he’d been interested in trying his hand at for a long time. “I listen to a lot of CBC radio and NPR,” he says. “I’m fascinated by talk radio. This was the first time I animated to interviews.”

Getting men, in particular, to share their stories was intentional. “I don’t think I’d ever heard guys talk about this, it’s not something they share openly in a dialogue,” Delannoy says. He began by interviewing his guy friends about how they got their sex talk, setting up a microphone in his St. Boniface home. His friends started talking to their friends. Soon, Delannoy started fielding calls from strangers who had heard about his project and were eager to share their stories. He compiled 35 interviews before deciding on the final eight.

“You have to see what actually works together and what makes a logical arc,” he says. “Which ones talk nicely to each other, which ones skew from the norm. One thing I discovered is there’s no one right way of doing this and everyone hopes they’ll do better than what they got — but I think we’re all kinda predestined to give terrible talks. But I think it’s positive we’re talking, regardless.”

These are childhood remembrances, and Delannoy’s dreamlike animations behave the way a child’s imagination would, a blend of memory and exaggeration: garish flowers exploding from dad’s shirt, a formative scene from The Terminator acted out with Barbie dolls, frog porn.

“There’s a lot of experimentation that goes into getting it just right,” he says.

There’s an ongoing texture in the background of the film, which is animated as well. “I looked at honeycombs. I looked at those little bags of feathers you can buy from Michael’s — but they were all too big and clunky,” he says. “But then I found these pillows at Jysk that were filled with down. I rigged up a scanner that I pumped all the feathers on, and they ended up giving me a texture that looks alive.”

Delannoy studied fine arts at the University of Manitoba, but most of his animation training was cobbled together from extra courses at Video Pool Media Arts Centre and the Winnipeg Film Group to supplement art school — as well as plenty of experimentation on his own.

“Initially, I thought it would be really cool to work in the industry, like in a big studio,” he says. “But more and more, when you get a taste of producing your own work, it’s quite fun because you can really dive in and present your own stories.”

Indeed, there’s a certain DIY ethos Winnipeg is known for — and few animators embody that spirit quite like Mike Maryniuk. Known for such kinetic works as the livestock auctioneer fever dream Cattle Call (2008) — his acclaimed collaboration with Matthew Rankin — Maryniuk is self-taught, and favours analogue techniques such as hand processing and scratch animation, which involves animating on the film itself “with, like, dentist tools and pins and stuff like that,” he says.

“Computer animation was starting to take hold, and to me it was like decorating a bird house as opposed to writing code or key framing or these things you do in the digital world. It was so small, it was ridiculous. It’s like animating on the space of the size of your pinky nail. Youg have to be very precise. It also prevented an enormous amount of people trying it and succeeding at it. I felt like I found this hole in the corner where I could kind of exist.”

After a prolific output of shorts, Maryniuk is stretching out over longer running times these days; his debut feature film, an absurdist adventure called The Goose (2018), premiered at the International Film Festival Rotterdam in January, and will screen in Winnipeg this summer.

While there is no uniform “Prairie esthetic,” there is something distinctly ‘Winnipeg’ about the films made by Maryniuk and others. One of Maryniuk’s formative influences was a Winnipeg animation called Five Cents a Copy (1980) by Ed Ackerman and Gregory Zbitnew, which has the distinction of being the first animated film made on a photocopier.

“That esthetic, that kind of paper, black and white, clumpy esthetic,” Maryniuk says. “The whole NFB jiggly lines — the nervous energy that everyone’s skin has in those films, the Cordell Barker films or The Big Snit. It’s so weird, everyone looks really nervy. The overall esthetic that I have — or what I draw inspiration from — is second-hand stores and ArtsJunktion (a local organization that collects and distributes reusable materials), just places where junk exists. I’m inspired by objects and castaways, things that have been forgotten or have outlived their usefulness. And that’s totally Winnipeg.

“Even our garbage dumps are fascinating,” he says. “They’re turned into toboggan hills.”

Leslie Supnet, another prolific local animator with a fondness for the lo-fi and the experimental whose work has shown internationally, knows it well.

“There’s definitely a hyper self-awareness with Winnipeg,” she says with a laugh. “It’s almost a genre or a trope, even, that we really focus on place because Winnipeg is so weird.

“You’re really frustrated about things in the city — real things, like transit or poverty or the harsh winter. Yet there’s something about it you love that can’t really be taken away from you. That definitely played into the kind of things I make; they’re often funny and sad. Tragicomedies, because Winnipeg is kind of a tragicomedy.”

Supnet, 38, can now take an outsider’s view of the city; she moved to Toronto in 2012. “It was mostly due to wanting and needing a change — a change in environment and scenery. I was also attracted to the amount of film stuff happening in Toronto. There’s TIFF and Images Festival and Toronto Reel Asian Festival. There’s just a lot happening all the time.”

Supnet noticed her esthetic also shifted when she left, moving away from the hand-drawn characters that defined earlier works such as How to Care for Introverts (2010) to more abstract stuff. “I think I felt like maybe I had exhausted my character-based stuff and wanted to explore and investigate something new,” she says.

Her latest film, The Peak Experience (2018), blends both worlds. She’s currently submitting it to festivals.

Six years in Toronto has made her reflect on Winnipeg and the influence it had on her. “The work from Winnipeg, there’s this level of campiness,” Supnet says. “It’s really absurd and campy. It’s not like that here. Everything in Toronto is quite serious and dry. Winnipeg is just totally, completely weird. And I miss that. I miss not thinking too hard about, ‘Is this art?’”

And so, she’s moving back in May. Toronto no longer makes sense for her and her husband, financially or artistically.

Winnipeg has also attracted animators. Alison Davis, 36, moved here in 2004, when she finished her BFA in film animation at Concordia University in Montreal. Davis makes both narrative and experimental films that are stylistically varied; The Origin of Ocean Rabbit is a cartoon-style dark comedy about imaginary friends meeting unfortunate ends, while Courtship (2008) is watercolour animation based on photographs.

“I heard that it was affordable,” she says of Winnipeg, laughing. “And also I had heard about the artist centres, (Winnipeg) Film Group and Video Pool and others here, that I knew would be able to support me making my films. I’ve been able to have a really good balance of mostly working part time and then doing art the other half, which is a really wonderful life balance I don’t know would be possible in other places.”

For Supnet and many of the other animators interviewed, organizations such as the Winnipeg Film Group and Video Pool were instrumental in helping her pursue animation.

“I found it really accessible,” she says. “At places like Video Pool and the Winnipeg Film Group, I was able to take artist-led workshops in all sorts of things — not just animation, but sound and circuit bending. It was an interesting way to find community.”

“The size of our city is nice,” Delannoy says. “There’s a lot of really talented people here — talented musicians, talented audio technicians, talented animators and filmmakers who you can ask questions and get feedback. There’s nice cross-pollination. We also have great support in the Winnipeg Film Group, On Screen Manitoba, Manitoba Arts Council, Winnipeg Arts Council — there’s lots of beautiful support here.”

For Jackie Traverse, 48, community is what helped her transfer her stories from canvas to screen. The Anishinaabe painter and multimedia artist teamed up with the Crossing Communities Art Project, a local not-for-profit arts organization, to help make three animated shorts: Butterfly (2007), an experimental tribute to missing and murdered Indigenous women; Two Scoops (2008), an affecting hand-drawn film about the ‘60s Scoop hitting too close to home; and Empty (2009), a companion to Two Scoops and a tribute to her estranged mother, who died at 27.

“These stories are so very personal,” she says. “I tried to paint them, and they didn’t come through. I tried sculpture, and that didn’t work. I tried print-making — but there was no other way to tell these stories except animation.”

Traverse was able to work with other local animators through Crossing Communities; Davis, in fact, helped edit the films, which continue to be screened. Empty was included as part of a recent Manitoba animation program curated by the Winnipeg Film Group’s Monica Lowe that also included work by other Winnipeg animators such as Davis, Supnet, Brenna George, Anita Lebeau and others.

For Traverse, making those films was critical to her own healing. “I felt so much lighter,” she says. “Carrying that childhood trauma with me was heavy baggage. I truly believe in the power of art and art therapy and how art can heal.”

Art has saved her life before. She lived “a really, really, really crazy life” until she was 30, cycling through the foster homes, group homes and, eventually, jail. She reconnected with making art — something she’s been doing since she was four — and vowed to change her life. She graduated from the U of M’s School of Fine Arts in 2009.

In the fall, Traverse will say goodbye to Winnipeg. She’s moving to Vancouver, where she says there is a larger market for her paintings. She’d love to make another animated film, if she can find the right team.

“I wish I could be doing animation,” she says. “I’m not skilled technically to edit — I’m just creative. I can tell stories, I can draw, I can paint, but I don’t have the technical know-how to do the rest. If I do another animation, I need a team of people helping me.”

Animation, in all of its many forms, has become an increasingly solitary pursuit. Veteran Winnipeg animator Patrick Lowe has seen technology’s effect on the scene first-hand.

“For one thing, the technology has changed a lot; it’s a lot more home-based now,” he says. “Before, you had to go to a sound studio to get your thing mixed. You had to go to an animation stand to get it shot. The equipment would be at the WFG or the NFB.”

Lowe came to Winnipeg from Kenora during the Condie/Caslor/Barker years, when the city was starting to make a name for itself as a hotbed for animation.

“I got a sponsorship from the NFB to make a short little film called Going Ape (1985) which I made when I was 17 and I was doing it on 16mm. It was my first attempt at a cartoon, done with traditional cell paintings.” Gerald the Genie — “my attempt to make the Great Canadian Short” — came out in 1997, followed by Lowe’s most popular animated film, A Bit Transcendental, in 2000.

As animation started moving into makeshift studios in bedrooms and basements, there was a loss of connectivity among artists.

“We’re not quite the community we used to be,” Lowe says. “Animators had more community with each other because we had to share the equipment or had to share the stand. Now, everyone has their own setup. They don’t even go to the same distributors. There’s still a filmmaking community, but it’s very individualized now. The community is there, but it’s different.”

Younger animators notice it, too. “There’s no, like, central hub where we all meet,” Davis says. “We’re all in our own little worlds, doing our own things. People have an idea and they’re like, ‘I’m going to do it.’ It seems very solitary. I like to work by myself when I’m making things, but it would be nice to have a community to meet up with and talk about what you’ve made and share it that way.”

The solo nature of animation can be its biggest draw. It can be as collaborative as you want it to be.

“You only have to count on yourself,” Maryniuk says. “You don’t have to manage egos the same way you would on a narrative film set, you don’t have to worry about managing other people’s schedules the way you would on a documentary, or the weather. You just need a dark place in your apartment or anywhere in Winnipeg to create these films.”

For Davis, that solitude is perhaps the city’s biggest influence on the films made here. “I think maybe that ties into the introvert thing about animation, and Winnipeg is a pretty isolated city. It’s like an introvert city all by itself. People aren’t trying to fit their work into a particular style. They’re a lot more focused on creating their own vision.”

Ask what makes Winnipeg such an incubator for creativity, and you’ll usually get an answer about winter. But perhaps it’s something else.

“I think an underdog spirit is there,” Maryniuk says. “I see it in a lot of filmmakers here. Like, almost hyper-defiant. Like, ‘Tell me I can’t do something and I’ll do it — and it’ll be great.’”

And whether we’re talking about the NFB heyday or today’s animation scene, that scrappiness — coupled with a strong work ethic — has consistently yielded work that punches above its weight.

“Sometimes, when I go to festivals, when I see the films that are being presented, it’s always underwhelming compared to a Winnipeg Film Group membership screening,” Maryniuk says. “People don’t realize. Because the work is so strong in Winnipeg, people will say, ‘Oh, what’s the point of submitting it to other festivals?’ But a middle-of-the-pack film in Winnipeg can lead a program in other places.”

The Winnipeg Film Group will screen Difficult Viewing and Listening: An Experimental Animation Retrospective, a program of local experimental animation on May 17 at 7 p.m. at Cinematheque. Curated by local animator Murray Toews, the program will feature works by a few of the animators featured in this story, including Alison Davis, Leslie Supnet and Patrick Lowe, along with others.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, April 28, 2018 10:13 AM CDT: Break added.

Updated on Saturday, April 28, 2018 12:38 PM CDT: Typos fixed.