Eureka! Ice sample collected during Cold War brings new answers to critical climate questions

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/03/2021 (1734 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A University of Manitoba professor is part of a team that has unearthed new information about the history of the Greenland ice sheet that stands to shift international thinking on how the frozen mass could melt in a warming climate.

The team’s research paper was published this week in the peer-reviewed journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. It shows inside of the last million years, Greenland’s ice sheet had melted entirely in a climate not much warmer than it is now.

How resilient the ice sheet is to warming is a topic of great discussion in climate sciences, as melt projections are difficult to pin down. How much melts, and how quickly, will impact global sea level.

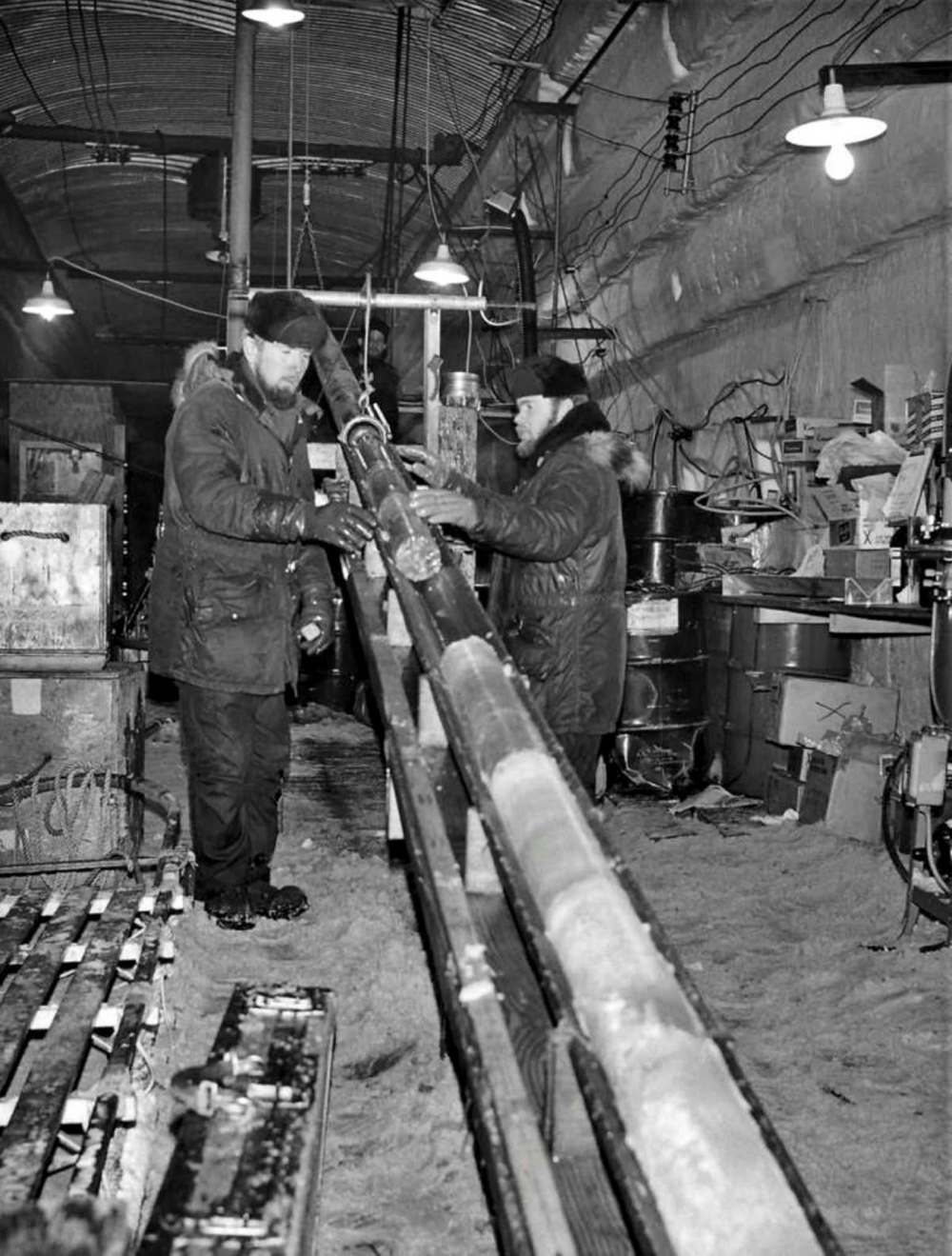

The research began with an ice core sample, initially 1.4 km in length, collected in 1966 at a Cold War-era U.S. military base called Camp Century in northwest Greenland.

Researchers at the time analyzed the ice collected, but left the soil sample that came up from the bottom unstudied.

The soil sample sat in a Danish university freezer for decades until 2017, when U of M Prof. Dorthe Dahl-Jensen got involved. Dahl-Jensen had previously worked out of the University of Copenhagen, and jumped at the opportunity to be involved in the research team that spanned four countries.

“It was very exciting to be a part of this,” she said in a phone interview from Denmark.

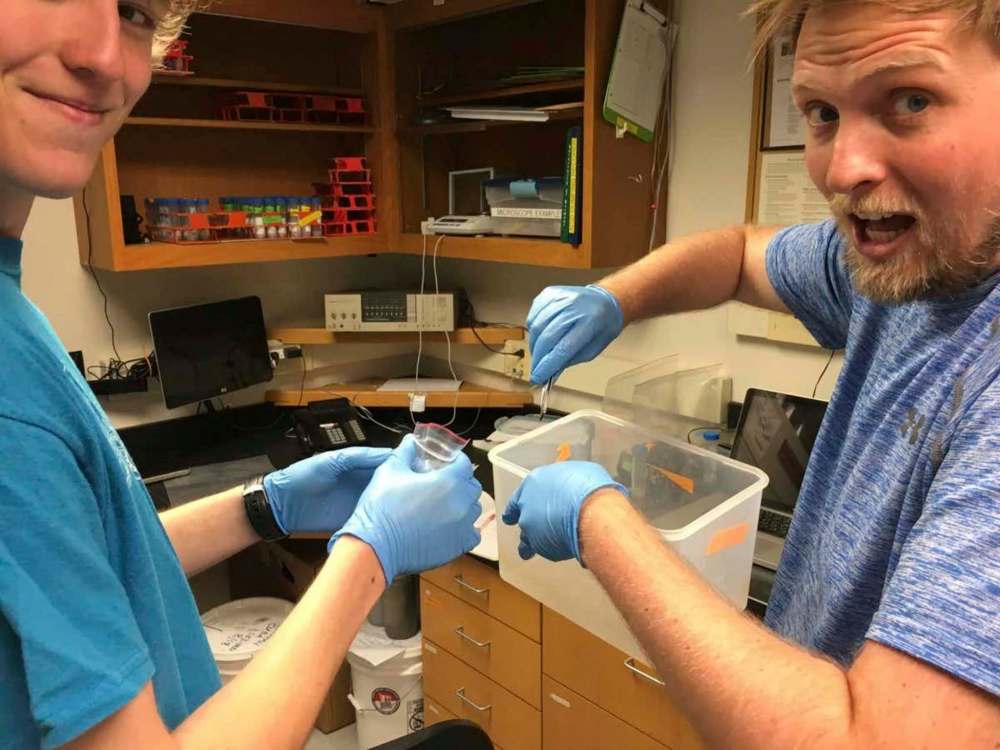

The soil sample was far from just dirt. When researchers started thawing and sifting through it at a laboratory at the University of Vermont in 2019, they found preserved leaves and other plant pieces.

“Ice sheets freeze and preserve material in a very pristine way. But it is a miracle to directly discover delicate plant structures perfectly preserved. They’re fossils, but they look like they died yesterday. It’s a time capsule of what used to live on Greenland that we wouldn’t be able to find anywhere else,” Dahl-Jensen said.

Drew Christ, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Vermont, was the one to first find the plant pieces. He calls it his first eureka moment, as the finding gave the sample an entirely new significance.

“Just by seeing those fossils alone, we knew that we had found evidence of a whole ecosystem underneath the Greenland ice sheet from the last time that it was gone. And that was just totally exciting,” Christ said.

While ice core samples are still collected, it can take up to a decade of time to see a project through, Christ told the Free Press. Additionally, it’s rare for sediment to come up with an ice sample. By gaining access to this material, it’s like the researchers got a chance to jump the line.

The last time Greenland was ice-free happened due to a natural warming period.

Sea levels at the time are estimated to have been between three and six metres higher than today, putting the land where current-day cities stand — such as Boston, London and Shanghai — underwater.

This time around, warming is being triggered by emissions from human activity on the planet and the combustion of fossil fuels.

Dahl-Jensen said the new information gives her some hope the ice sheet is perhaps more resilient than research has previously suggested. For the entirety of the ice sheet to melt, it could take a thousand years, she said.

However, the entirety need not melt to cause devastating impacts to coastal communities around the world, and it is sensitive to changes in climate.

The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets contain roughly 99 per cent of the world’s freshwater ice. Researched published in Nature suggests the Greenland ice sheet will melt faster this century than at any point in the last 12,000 years.

Even if warming is limited to 2 C, the ice sheet will lose roughly 8,800 billion tonnes of ice per century.

“The Camp Century base was built at a time when the existential threat was a nuclear war… the worry of intercontinental ballistic missiles flying across the Arctic between the Soviet Union and the U.S.,” Christ said.

“That the science project that they did, on the side, of Camp Century has helped expose this other human-caused existential threat of climate change, and the threat of melting the polar ice sheets and rising sea level — yeah, there’s just sort of that historical irony.”

sarah.lawrynuik@freepress.mb.ca