A burning issue in Winnipeg’s inner-city North End streets pockmarked with charred shells of vacant properties set aflame by shelter-seeking squatters, leaving residents on edge, draining firefighting resources

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/04/2023 (1018 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Cindy Cook can point to multiple homes in her North End neighbourhood that have sat boarded up and burned out for months, maybe even years.

When a nearby vacant building on Selkirk Avenue went up in flames earlier this month, she shrugged it off; another empty home left to rot after a fire could be found just a short walk away.

While it’s nothing new, she said, it has suddenly gotten worse.

“There’s good years and bad years, just like any, but the last five years has gotten really bad,” Cook said at a Pritchard Avenue park near her home.

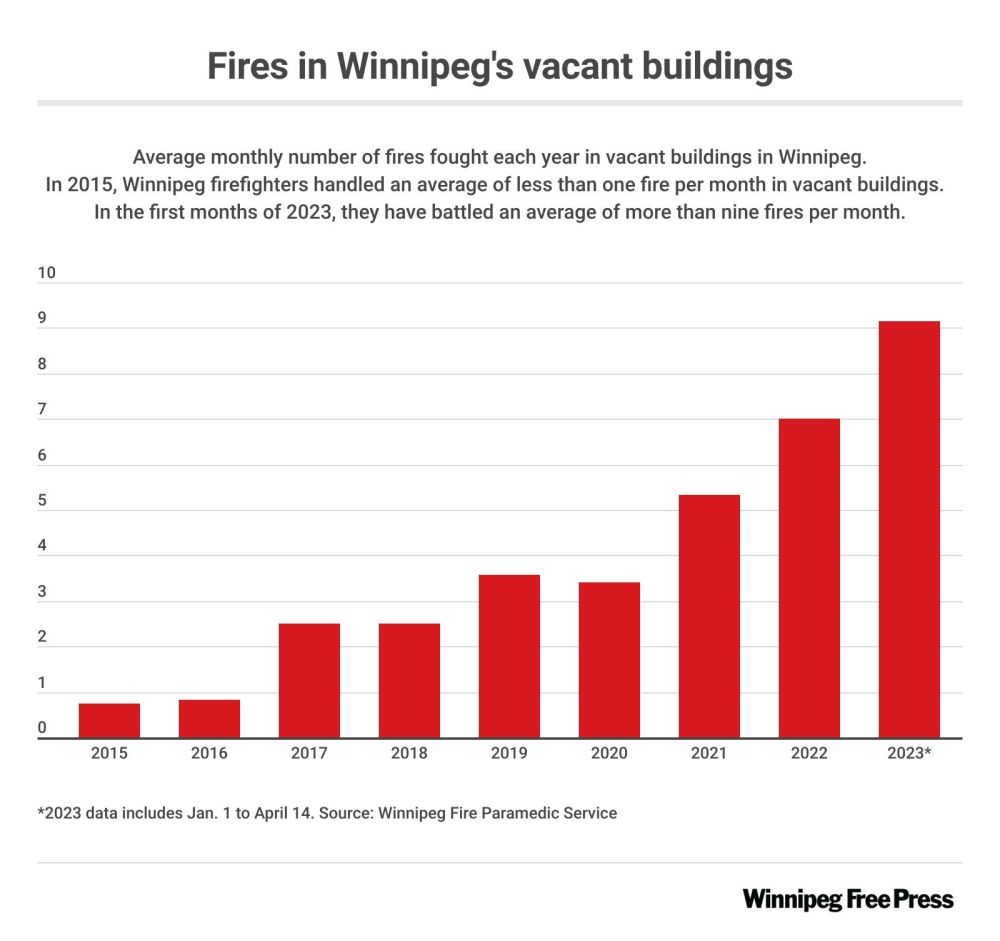

Numbers provided by the Winnipeg Fire and Paramedic Service reflect her concerns. The number of fires in vacant buildings the WFPS is responding to has grown exponentially since 2015.

In 2022, fire crews extinguished 84 vacant building fires — 25 per cent more than the year prior (64) and more than nine times more than in 2015 (just nine).

With 32 fires fought in vacant buildings from Jan. 1-April 14 of this year alone, there’s nothing to suggest the problem is getting any better.

After a second fire in six months Wednesday, a now-vacant Logan Avenue home will be demolished. A fire at the same home in November killed a 45-year-old man.

Cook shakes her head thinking of the vacant building fires she’s witnessed in her 15 years in William Whyte. At one point, the attached home in the duplex where she lives was vacant and populated by squatters. She was living in fear they would start a fire that would spread.

“I was scared. I live alone. Are they going to come to my door? What are they capable of doing? And if they set that house on fire, then I don’t have a home, and I’ve been there for 15 years,” she said.

Cook wants to see systemic changes, not Band-Aid solutions. When she sees unhoused people in her community take to empty buildings after struggling to stay warm outdoors during long Winnipeg winters, or police showing up late or not at all to reports of squatting, she wonders why there isn’t more urgency in the city’s struggle to handle derelict buildings.

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Cindy Cook shakes her head thinking of the vacant building fires she’s witnessed in her 15 years in William Whyte.

“When you walk down the street, how can you take pride in your community when there’s three or four burned houses?” she said.

When city fire crews respond to a blaze in a derelict building, it poses a unique safety risk — often the condition of the structure was already deteriorating. Fires in abandoned buildings often take longer to be discovered and reported.

With those factors in mind, crews try to work defensively to keep themselves safe, said WFPS assistant chief Scott Wilkinson.

“If the building is such that it’s unsafe to enter, and we don’t have any signs of persons requiring rescue, then we’re going to take a little bit more methodical, defensive approach and working from the outside to make sure that we’re not putting our people at risk,” he told the Free Press Wednesday.

Responding to vacant properties takes up what he called a “fairly significant” commitment of resources. In 2022, the WFPS responded to 2,545 fires, 784 of them structural, meaning nearly 10 per cent of all structural fires were at vacant buildings.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS After a second fire in six months Wednesday, a now-vacant Logan Avenue home is being demolished.

“Those resources are always on standby for any type of incident,” Wilkinson said.

“The biggest issue comes that while, obviously, those resources are committed at those incidents, it does affect our ability to respond to other incidents. Our communications team does a great job moving and relocating our available apparatus around the city to ensure an adequate response. But inevitably, we are somewhat limited in that response, once we commit a lot of apparatus in one area to that type of incident.”

There are some initiatives that Wilkinson believes will reduce the number of fires, including a task force put in place last summer to do monthly checks at “high-profile” vacant homes, or those fire crews have had to return to more than once, to ensure they remain properly boarded up.

The team is already finding that, over time, fewer properties require repeated attention, he said.

The WFPS has also begun invoicing building owners for fire responses at vacant structures.

“Our (fire) numbers have continued to rise. We’ve got a lot of recent efforts, and a lot of good successes…. The reality is, it’s going to take time to see those efforts reflected in the numbers,” he said.

Ideally, there would be more done to ensure that vacant buildings could be quickly obtained and repurposed by the city and province into affordable housing, he said.

“When these homes are burning, once they’re significantly destroyed, we lose the ability for them to be that affordable housing,” he said. “So the more we can rehabilitate and put people in them ahead of time, and/or keep them secure, the better off we are.”

There are approximately 660 vacant buildings in Winnipeg.

Bylaw enforcement and fining owners is a very small step towards fixing a very big problem, said Coun. Ross Eadie.

In his Mynarski ward, many of the owners of derelict buildings aren’t slumlords who own dozens of properties, but rather people who won’t be able to afford to pay off the fines anyway.

He’d like to see more investment from the city toward making the process of renovating the homes easier and less expensive.

“(Bylaw enforcement) says that city council and the public service are doing stuff, but it has to come down to how do we help people care for their properties?” he said.

“It’s horrible. It’s the worst sign of urban decay. And the emotional impact on people living on the street is, ‘Nobody cares about us, I’ve got to watch my back all the time, is that house going to burn?’”–Community advocate Sel Burrows

Longtime community advocate Sel Burrows has worked with bylaw enforcement at inner-city derelict buildings and watched the system move slowly, ranging from city bylaw enforcement taking months to issue orders to properly secure buildings to a lack of any followup inspection process.

“Some of them sit out there for years, and they’re not supposed to be allowed to remain vacant more than a year,” he said.

He has also watched that slow-moving process take its toll on community members. He points to Pritchard Avenue, near Cook’s home, where he said there are more than a dozen vacant homes, half of them burned out.

“It’s horrible. It’s the worst sign of urban decay. And the emotional impact on people living on the street is, ‘Nobody cares about us, I’ve got to watch my back all the time, is that house going to burn?’” he said.

“And one of the impacts is that those people not living on the street who are able to, quite often will move away. And so your more stable, better-able residents, particularly owners and renters, leave.”

malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca

Malak Abas is a city reporter at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg’s North End, she led the campus paper at the University of Manitoba before joining the Free Press in 2020. Read more about Malak.

Every piece of reporting Malak produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.