Aging in the wrong place The weight of the wait for a care-home bed in rural Manitoba can be crushing for seniors languishing in hospitals far from friends and family and on loved ones forced to drive long distances to see them

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/12/2024 (390 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Mervin Friesen thought his mother would be in a personal care home — she’s been awaiting placement for four months.

Instead, he travels 40 minutes to visit her at Morris General Hospital, where she pays roughly $73 per night for a bed, Friesen said. It’s the same cost she’d pay to live in the Niverville personal care home she desperately wants to move in to.

Niverville is where Helen Friesen, now 90, grew up and where her friends live.

“She’s very frustrated,” her son said. “Obviously, we are too.”

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS Mervin Friesen is frustrated that he is unable to get his mother into personal care home bed in a facility in their community of Niverville which he estimated he spent thousands of dollars to help build during a rally about a decade ago.

Unlike many rural Manitoba residents, the Friesens have a personal-care home in their neighbourhood.

They helped to pay for it — spent thousands of dollars, by Mervin Friesen’s recollection — when the community rallied a decade ago to erect a seniors living facility.

Even the relatively new build has a wait list of more than 20 people. So the Friesens keep waiting.

Aging facilities, a lack of beds and chronic staffing shortages plague personal care homes in rural areas.

In three health regions — Interlake-Eastern, Prairie Mountain and the Southern authority — 610 people were waiting for a care home spot on Nov. 27. All the facilities operated by Northern Health were full, with an average wait time of 167.5 days.

Average wait times for Interlake-Eastern and Prairie Mountain regions were 86 and 83 days, respectively.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS Mervin Friesen holds a photograph of his mother Helen, a Niverville resident who has been waiting for a personal care home bed in her own community for four months.

In some cases, Manitobans languish in hospitals while care home beds are unoccupied due to staff shortages. Municipalities push for provincial funding to upgrade their facilities while relatives are forced to hit the road in order to visit loved ones who can no longer live independently.

It’s been the state of rural personal care homes for years — and it doesn’t seem to be changing.

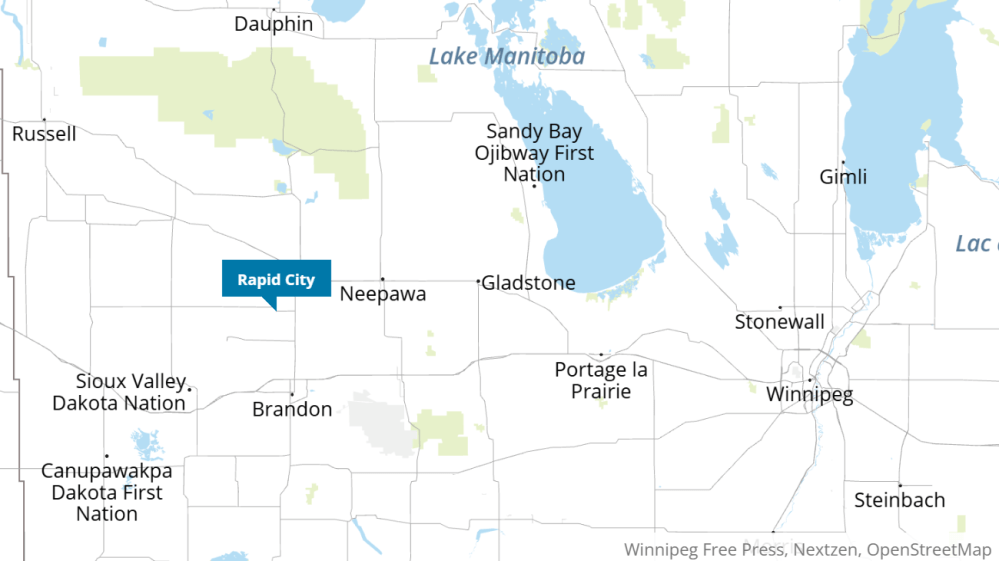

Bryan Hill bought a place in Rapid City, about 30 kilometres north of Brandon, nearly a decade ago. In terms of demographics, it’s the province’s oldest municipality.

The home was a necessity: he and his mother, Margaret Hamilton, could live separately — she’d have a downstairs suite — but he could still care for her as her dementia progressed.

Rapid City is in the Rural Municipality of Oakview, where the average age of residents was 60.2 as of June 1, 2023, making it, by a sliver, the oldest population of a Manitoba municipality; Russell-Binscarth residents had an average age of 59.9, according to provincial data.

Hamilton fell in October 2023 and experienced a sharp decline in health as a result, Hill recounted.

Her pain increased and the dementia got worse while she recovered at home. In January, she was admitted to Brandon Regional Health Centre and, after a few days, she was moved to a transitional bed in Hamiota’s hospital — about 45 kilometres west of Rapid City and 85 kilometres northwest of Brandon — while waiting for a personal care opening.

Her son added her name to every personal care home list in Brandon.

“It was basically a waiting game,” Hill said.

While they waited, his mother was moved again, to a hospital in Baldur. The drive was about 90 minutes each way.

“It would’ve been nice if there was a place closer while we were waiting,” Hill said. “We had limited access to her for, really, close to six months because she was just so far away.”

“It would’ve been nice if there was a place closer while we were waiting.”–Bryan Hill

All hospitals in the RM of Oakview fall under the Prairie Mountain Health umbrella.

Hamilton, 84, was paying as though she were already in a personal care facility. The charges began once she was approved by a personal care home panel; it’s the case for all seniors in her situation.

The rate is based on a resident’s income and ranges from $41.80 to $101.10 per day. Prairie Mountain Health collected $2.84 million in revenue during the 2023-24 fiscal year for all “waiting placement” clients in transitional and acute-care beds, which includes people waiting for personal care home beds.

Southern Health collected $1.79 million during the same fiscal year; Northern Health received $71,925. The Interlake-Eastern Regional Health Authority took in $627,250 from people who’d been panelled and were waiting in hospital for a placement between November 2023 and October 2024 — the money contributes to the cost of care provided, a spokesperson said.

Hill said his mom had good care in the hospital; a speech therapist and other specialists treated her, including changing her medication.

“She’s so much better than she was,” he said.

However, he could see her only once a week when she lived in Baldur, and trips were weather-dependent. Hamilton got a spot in Brandon’s Hillcrest Place Personal Care Home in June, and she’s doing well there, Hill said.

Neither he nor Mervin Friesen think it’s right for hospital beds to be used as waiting rooms for people headed to personal care homes. Hill was told staffing shortages affected his mother’s placement.

On Nov. 27, at least 287 acute and transitional hospital beds were used by people awaiting PCH placement, not including Northern Health and Winnipeg patients.

It’s common: residents age, need more care and leave the RM of Oakview.

They often go to nearby Brandon, Minnedosa or Hamiota, said Reeve Robert Christie, who oversees a municipality of 1,630 people. A personal care home is “hard to warrant,” especially with neighbouring facilities and a shrinking tax base.

“We’re struggling right now to keep a little Co-op food store (open),” Christie said.

More than half of the municipality’s population — 52.4 per cent in 2023 — is at least 65 years old.

So, older people leave and younger generations move away for post-secondary education and don’t always return, Christie said.

He’s focusing on marketing the RM as a place with little crime, low taxes and an affordable cost of living so the municipality can “keep surviving.”

Rural communities need a wide range of housing options — from assisted living to personal care homes — to allow elderly Manitobans to age in place, said Gordon Daman, who was voluntary president of Niverville’s personal care home when it was built.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS David Sawatzky (centre) is helped by nurse Cherry Ponc with Wilhelm Funk at right at the Niverville Heritage Centre, which usually has a wait list of about two dozen people.

Daman has become a consultant for rural communities wanting to build their own seniors facilities. A popular model that’s emerging is the “hub and spoke” in which several municipalities group together to create an assisted-living complex in a larger neighbourhood. Once that’s established, the group will build smaller sites in surrounding municipalities and share funds, staff and food services.

The RM of Oakview has joined six other governments to create a “hub and spoke” campus. The assembly — called the Valley Life Housing Group — aims to build an assisted-living facility in Minnedosa, with smaller options nearby.

“They will be able to ‘spoke’ services out into smaller communities, into areas like Oakview,” explained Daman, who’s a consultant on the project.

Four municipalities and a town are working toward a “hub and spoke” model in Carman; efforts are ongoing in Dugald, Boissevain and Dominion City, he said.

Still, provincial funding is critical for municipalities with personal care home plans, mayors told the Free Press. The cost of construction per bed has ballooned since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The costs swelled over the past 12 years, which is when discussions began about building a new care home in Lac du Bonnet.

The project was announced by the Manitoba government, under the NDP, in 2012. In 2017, the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Pallister cancelled the plans; the party reversed course with Heather Stefanson at the helm in the summer of 2023, just before the election.

Then in March, Wab Kinew’s NDP government confirmed it was moving ahead with funding the 95-bed facility in the municipality, 100 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg.

“We’re hoping that (this) will really provide some serious alleviation to the needs of the community,” said Lac du Bonnet Mayor Ken Lodge.

“We’re hoping that (this) will really provide some serious alleviation to the needs of the community.”–Lac du Bonnet Mayor Ken Lodge

Work to prepare the site for construction began this month. The care home will replace a 30-bed facility, which is 41 years old and has a constant waiting list. On Dec. 13, four people were waiting for a bed in Lac du Bonnet. It’s common for people to wait in hospital for a bed to become available.

“The town itself has become… more senior-oriented,” Lodge said.

People who once lived on area farms have moved into town and cottagers have become permanent residents. As a result, new apartments and condominiums have sprouted up, Lodge noted.

Lac du Bonnet’s decades-old care home is tied to an assisted living centre. Once the new facility opens — planned for 2027 — assisted living may be expanded into the current 30-bed space, Lodge said.

Forty-one per cent of the RM of Lac du Bonnet’s population was at least 65 years old in June 2023. Seniors are leaving for elder-focused housing, including personal care homes, and for access to health facilities, he said, adding that people want to stay close to their families.

The town is contributing more than $1 million to the new care home, which was estimated to cost $66.4 million in March.

Lodge is concerned about staffing the incoming site.

“There’s no point in building it and then having to leave two or three of the wings (unoccupied),” he said.

Lodge expects the facility will need at least 100 employees. Lac du Bonnet struggles to find health-care staff — it has started its own doctor-recruitment program — and he figures all 95 beds will be needed.

In Carman, about 90 kilometres southwest of Winnipeg, two sections of Boyne Lodge Personal Care Home are closed due to the lack of staff, Southern Health confirmed. It didn’t specify how many beds were empty.

The Carman home has 105 beds — 79 in a new, main facility, and 26 in older and renovated units.

Southern Health’s recruitment efforts are targeted for personal care home workers to fill openings throughout the region, a spokesperson said.

The regional authority has utilized job board postings, attended career fairs, collaborated with educational institutions and offered relocation incentives, among other things.

Manitoba’s other rural health authorities are undertaking similar efforts. A spokesperson for the Interlake-Eastern Regional Health Authority noted staffing vacancies wouldn’t contribute to beds not being filled; facilities use private-agency workers when needed.

Five municipal governments — the Town of Carman and the RMs of Dufferin, Grey, Roland and Thompson — created Boyne Care Holdings to build a 79-bed personal care home to add to Carman’s longstanding facility.

Boyne Care Holdings runs the building’s food and maintenance operations. Southern Health covers the direct care and housekeeping and pays Boyne Care for the other services.

“We knew that the existing facility was dated and very institutional… and we wanted to look at doing improvements and expanding,” said Tyler King, executive director of Boyne Care Holdings.

“We knew, at the time, that there wasn’t a large appetite (from government) to be able to do those kinds of things unless we looked at some innovative ways of doing it.”

“We knew that the existing facility was dated and very institutional… and we wanted to look at doing improvements and expanding.”–Tyler King, executive director of Boyne Care Holdings

The communities began their efforts in 2018 and ultimately raised about $8 million through donations and municipal grants. The remaining funding came from the province and a mortgage Boyne Care Holdings took on. It services the mortgage through commercial space rentals, its service agreement with Southern Health and a bistro it operates in the care home. The site opened in 2021.

The next goal, King said, is to start building a 52-unit assisted-living centre in Carman in the new year. Assisted-living centres should open in neighbouring communities in succeeding years, he said.

Boyne Care Holdings took a page from Niverville, which built its own seniors living centre — including an 80-bed personal care home and assisted-living units — in 2013.

The community built it without government money after obtaining a licence for a personal care home. Residents donated upwards of $1.2 million, and contractors dropped their market rates by 25 per cent.

Two-thirds of the facility’s annual funding comes from the province; the latter third is from residents’ rent, similar to other care home models, said Ron Parent, executive director of the Niverville Heritage Centre.

The centre, a community hub, also has an 82-space daycare, medical and dental clinics, pharmacy, restaurant and event centre. Approximately 1,000 people visit the site weekly, Parent said.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS Niverville mayor Myron Dyck outside the Heritage Centre, which acts as a community hub that includes a seniors living centre, daycare, medical and dental clinics and other spaces.

“To have it in your community just goes to the overall well-being of the community,” said Niverville Mayor Myron Dyck. “(It’s) very important for people as they age in place.”

The centre could use more beds, Parent noted, adding the wait list regularly has 20 to 25 people on it. One of the list’s current names is Helen Friesen, at Morris General Hospital.

“(In) rural Manitoba, so many individuals spend so much time in hospitals waiting to access a long-term care bed,” said Sue Vovchuk, executive director of the Long Term and Continuing Care Association of Manitoba.

“An individual who needs to go into long-term care, they need to be in that supportive, wonderful environment of long-term care, not sitting in acute care.”

Arborg is among six communities selected for a personal care home by the former Progressive Conservative government just months before it lost the 2023 election.

The Interlake town is trying to get things rolling on a much-needed 60-bed home, but it’s unclear whether the project will move forward, Mayor Peter Dueck said.

gabrielle.piche@winnipegfreepress.com

A brief look at a First Nations personal care home

Just eight of 63 First Nations communities in Manitoba have personal care homes.

Two are licensed through, and receive funding from, the provincial government. The other six receive federal funding and are not licensed through Manitoba Health.

Rod McGillivray Memorial Care Home in Opaskwayak Cree Nation is among the six operating with federal money. Its 28 beds are always at capacity, said Carla Constant, the site’s care home administrator.

Band members from OCN and nearby First Nations make up the residential population. They receive First Nations-specific care — for example, going to community powwows and eating wild game donated by local hunters.

There are sharing circles and mental-health supports so seniors can live mino-pimatisiwin, or “the good life,” said Constant, who’s worked at the home since 2021.

“Even though we are a health-care setting, it’s… not like an institutional setting,” she added.

Because the home isn’t licensed through the province, it has the flexibility to do things such as offering locally hunted moose meat to its residents, she said.

However, the care home’s funding hasn’t kept up with inflation, and that has put a strain on some operations, but not patient safety, Constant said.

The home employs 66 people, mainly from OCN and The Pas, but it relies on agency health-care aides and nurses to fill gaps, which comes at a large cost.

The building is also aging — it’s 42 years old — and needs renovations soon, Constant said. The site’s wait list sat at 15 people on Dec. 16.

It’s important to have elder community members receiving care near family — they’ve provided “major contributions” to the community and should be valued, she noted.

A federal health inspector visits OCN’s care home regularly, and the site follows best-practice guidelines, she said.

— Gabrielle Piché

Gabrielle Piché reports on business for the Free Press. She interned at the Free Press and worked for its sister outlet, Canstar Community News, before entering the business beat in 2021. Read more about Gabrielle.

Every piece of reporting Gabrielle produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.