Tireless advocate for change

Trailblazing lawyer Marion Ironquil Meadmore was a champion for Indigenous self-governance, economic development

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/02/2025 (278 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On the first day of boarding school in a classroom full of non-Indigenous strangers, the teacher announced it was French class.

“I didn’t know French,” recalled Marion Ironquil Meadmore. “I didn’t even know what French was!”

Knowing full well Marion hadn’t been learning the French language at residential school, the teacher asked her to stand up and read an entire page out loud to the class.

SUPPLIED

Marion Ironquil Meadmore in her grad photo from the Unversity of Manitoba faculty of law in 1977. Ironquil Meadmore was the first Indigenous female Canadian to be called to the bar.

“The kids were laughing hysterically,” Marion recalled. “I was humiliated, but I wasn’t backing down. So I read the whole page. The kids actually respected me after that.”

It was a demonstration of the strong resolve that would spur her remarkable accomplishments in later life. There aren’t many Winnipeggers who have had a bigger impact on our city.

Marion was born in 1935 in Peepeekisis Cree Nation, 100 kilometres northeast of Regina, the same part of the province in which she attended File Hills Indian Residential School from age six to 13.

The school was closed in 1949 after a government inspection determined it to be a fire hazard and “a first-class germ trap.” The inspection report stated: “A complete medical check-up should be made of all inmates of the institution, and if repairs are not carried out, it would be criminal neglect.”

After a two-year stint at boarding school in Strasbourg, Sask., Marion was then sent to Birtle Indian Residential School in western Manitoba. At age 18, her determination led her to move to Winnipeg to attend pre-med courses, but she quickly found out residential schools hadn’t prepared her for university.

Marion recalled that it was in Winnipeg where she noticed there was to be a conference regarding the “Indian problem” — prejudicial words that would motivate her for the rest of her life.

Leadership skills ran in Marion’s family. Her father, Joe Ironquil, was of Ojibwe heritage, but he also spoke Cree, Sioux and English. Joe went on to graduate from the University of Manitoba with a bachelor of agriculture degree in 1919, making him one of Manitoba’s earliest Indigenous university graduates.

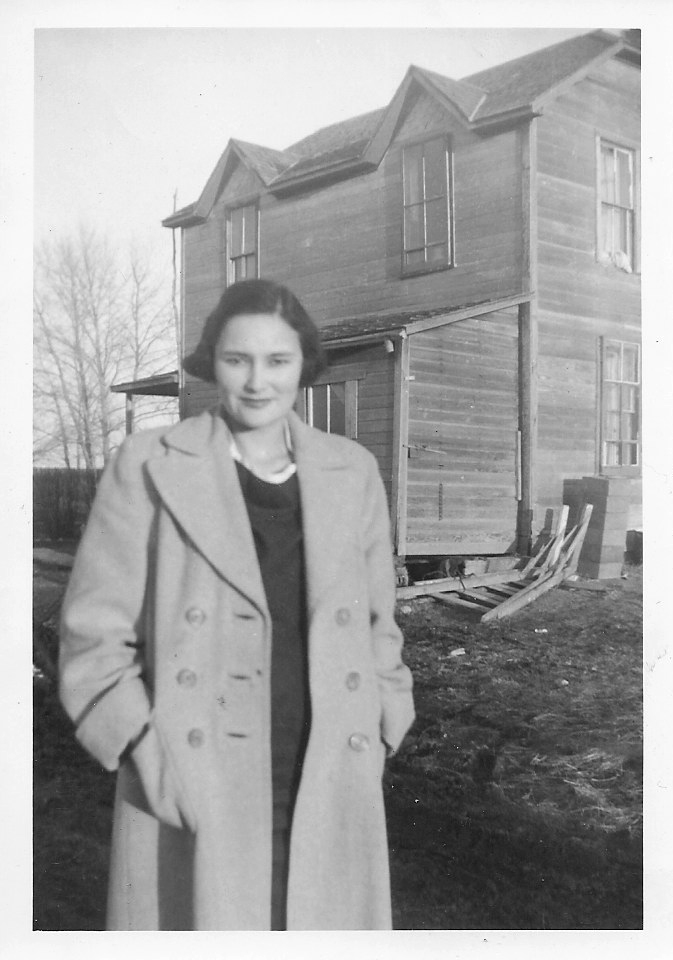

Marion Ironquil at the family home on Peepeekisis Cree Nation in Saskatchewan.

Joe became chief of Peepeekisis Cree Nation when Marion was a child. (I think of Joe when I type out ‘Ironquil’ — he spelled it with one ‘l’ to make forgery more difficult, he said.) After the death of his first wife, Joe married Helen Poitras, who was of both Cree and Métis heritage.

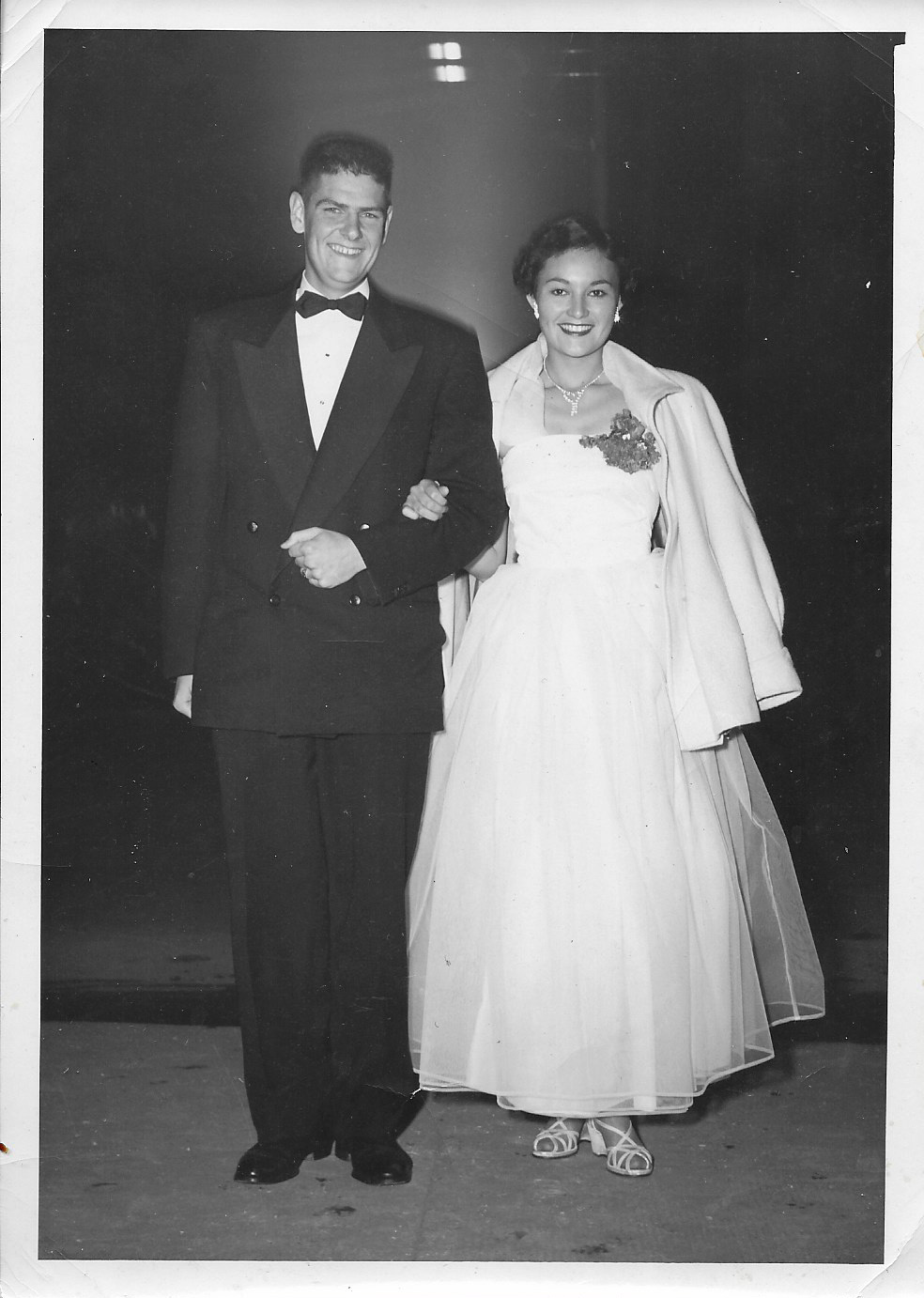

In 1956, Marion married Ron Meadmore, a soft-spoken farmer from Culross, who later went on to have a storied CFL career, winning three Grey Cups as a defensive end with the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. Ron would farm in the mornings and then drive into Winnipeg for practices or games.

When asked how he managed being married to an Indigenous activist always on the move, Marion smiled and said, “He was always so supportive of me. Everything I did, he never complained.”

With Marion often on the road making good things happen, Helen would often step in to help raise Marion and Ron’s three boys.

Queried on what it was like being the only Indigenous person at Blue Bomber functions, she said, “I wasn’t the only one. Jack Jacobs was there too. And besides, Bud Grant treated me really nice. I felt included.”

Remarkably for the time, neither Marion’s nor Ron’s family members questioned their interracial marriage. The two had been happily married for nearly 57 years when Ron died in 2013.

SUPPLIED

In 1954, the Winnipeg Free Press referred to Marion as an ‘Indian Princess.

In 1959, at just 25 years old, Marion noticed the growing number of Indigenous people moving to Winnipeg.

“We needed a place to meet, to connect to each other,” Marion recalled thinking. Spurred to action and inspired by an organization she had seen in the United States, she co-founded Canada’s first Indian and Métis Friendship Centre, which grew into a network of more than 100 similar spaces across the country.

As the 1960s dawned, Marion recalled thinking, “We need to advocate for ourselves,” so she became a co-founder of the National Indian Council in Winnipeg in 1961, Canada’s first national body advocating for the rights of First Nations people.

The NIC eventually morphed into Assembly of First Nations, and Marion served as the organization’s first secretary-treasurer.

By 1970, housing had become a critical issue for Indigenous families moving to Winnipeg.

Marion recalled gathering friends in her living room and telling them, “We need homes for our people. No one is leaving here until we figure this out.”

Marion Ironquil married Ron Meadmore in 1956.

This led to the formation of Kinew Housing, Canada’s first Indigenous housing corporation.

Today, Kinew Housing provides single-family dwellings in Winnipeg to more than 400 Indigenous families and has around $60 million in assets. The non-profit organization served as a model that has been replicated many times across Canada.

Marion graduated from law school at the University of Manitoba in 1977 and after being called to the bar, became Canada’s first Indigenous female lawyer.

According to Marion, her decision to study law was, “a bit of a lark,” as she and her friend Delia Opekokew accepted a professor’s challenge to pursue a law degree. Opekokew graduated six months after Marion, who went on to co-found Winnipeg’s first all-female law firm.

In 1982, Marion turned her attention to Indigenous business development, founding the National Indian Business Association which supported dozens of Indigenous entrepreneurs. In 1988, she established Arrowfax Canada, a successful business publishing directories of First Nations and Indigenous organizations across North America.

Winnipeggers may remember Bungee’s Restaurant on Edmonton Street. Marion and Ron supported the business with their own personal mortgage to proprietor Mary Richard. Marion proudly said Richard never missed a payment.

In 1984, Marion was appointed to the Order of Canada for her achievements in law and business and sat at a table with fellow recipient Anne Murray, the Grammy-winning singer.

SUPPLIED

Marion Ironquil Meadmore and husband Ron Meadmore.

Marion was also an accomplished athlete. She organized and pitched for the Arrowettes, a women’s baseball team that played in Winnipeg’s North End for 17 years.

The team represented Manitoba at the first North American Indigenous Games in 1990, where Marion, at age 55, pitched Manitoba to a gold medal and also won bronze in archery.

She recounted a story about playing in a Winnipeg law baseball league against Fran Huck, a former Winnipeg Jets player who was nine years her junior.

Marion beamed telling me she fought him to a full count and then put him out on a high fly ball. “He swung harrrd,” she said. “The ball went waaay up in the air. He was around third base before I caught it.”

I asked her what pitches she had. She replied, “I had two pitches. Fast and faster.”

In 2014, during the height of my social enterprise career, I attended an Indspire Awards ceremony in Winnipeg. Marion was being honoured, but like many Winnipeggers, I hadn’t heard of her before.

SUPPLIED

Marion Ironquil Meadmore in 2025 with her Arrowettes uniform.

Astonished by her impact on the city, I reached out and we became instant friends. While her work had already impacted mine, she became my mentor, offering wisdom about social enterprises and Indigenous wealth-building.

In June 2024, she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Manitoba.

In her convocation speech, she highlighted Indigenous accomplishments in finance, sport, education and journalism. “There is no ‘Indian problem,’” she declared.

I asked Marion how she coped with the anger from her residential school experiences, and she said, “I think I always looked forward to how I could be helpful.”

When I told her I was writing this piece, she said she had a message for Winnipeg: “Tell them I’m thankful for everything. You gave me my education and my friends too. I’m very grateful.”

She had recently described herself as a leaf on a tree in autumn, saying, “I’m going to fall to the ground, and when I get there, I’ll have to go right back to work.”

SUPPLIED

Shaun Loney with his mentor, Marion Ironquil Meadmore, in 2016.

Marion leaves behind three loving sons and their partners, three grandchildren, a sister, and numerous relatives, friends and colleagues.

Surrounded by family at her Winnipeg home, Marion passed away peacefully on Feb. 19. She was 89.

Shaun Loney works in the social-enterprise sector. Marion Ironquil Meadmore was a mentor to Loney and helped him with his second book, The Beautiful Bailout.

History

Updated on Thursday, February 20, 2025 3:25 PM CST: Adds quotes.