‘Hard truths’: Indigenous, Black patients wait longer to be seen in Winnipeg hospitals

Race-based data used as benchmark to improve in the future

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/06/2025 (206 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Race-based data collected from Winnipeg hospital emergency department patients show racism can be a factor that affects wait times and care, the project’s lead said Tuesday.

“Today, we’re talking about some hard truths,” Dr. Marcia Anderson said at a news conference Tuesday with Health Minister Uzoma Asagwara and Dr. Shawn Young, chief operating officer of the Health Sciences Centre.

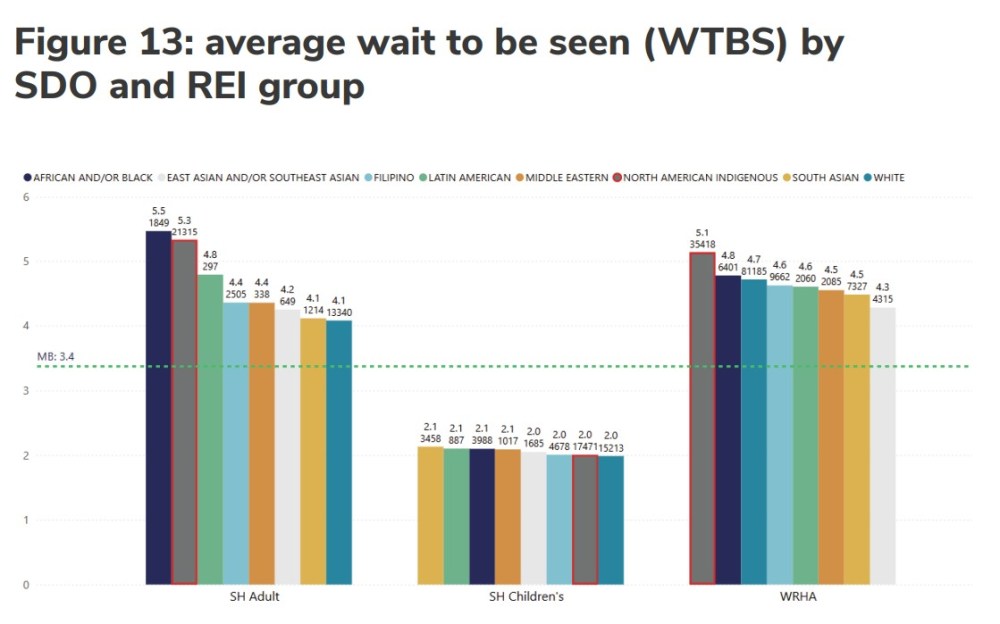

Anderson said adult African/Black adult patients waited the longest to be seen (an average of 5.5 hours between patient assessment and treatment at Health Sciences Centre), data collected from May 2023 to September 2024 show. Indigenous adults waited the second longest at 5.3 hours. Those who identified as white had the shortest wait at 4.1 hours. The average Manitoba wait time for all ages was 3.4 hours.

The findings will be used as a “benchmark,” she said.

“Going forward, we hope to be able to share markers of progress,” said Anderson, vice-dean of Indigenous health, social justice and anti-racism at the University of Manitoba’s Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

Manitoba hospitals became the first in Canada to collect voluntary data about patients’ race, ethnicity and Indigenous identity. The information was gathered by Shared Health in collaboration with the U of M’s Ongomiizwin Indigenous Institute of Health and Healing and the George & Fay Yee Centre for Healthcare Innovation.

- Read the report: Race, Ethnicity & Indigenous Identity Data: Emergency Department Visits & Care (PDF)

Hospital patients were asked to self-identify during registration, and of 618,803 responses, 50.7 per cent identified as white, nearly 37 per cent as Indigenous, nearly four per cent as Filipino, and 2.8 per cent as African and/or Black.

“Unfortunately, in a system under stress, it is often those who are the most marginalized and have the fewest resources who are impacted the most.”–Dr. Marcia Anderson

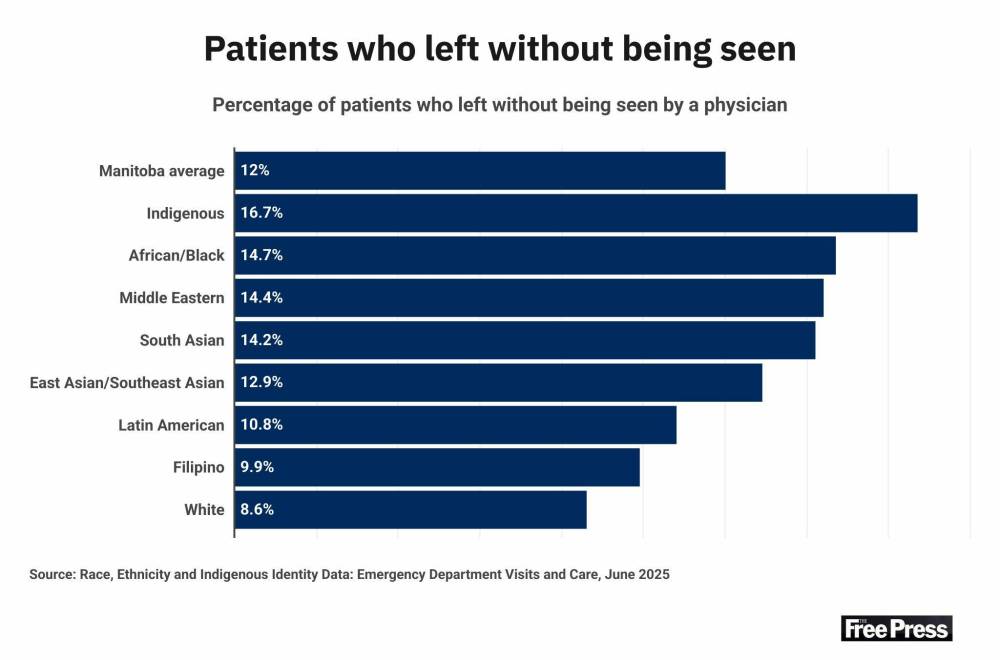

Those who identified as Indigenous were mostly likely to leave hospital without being seen by a physician (16.7 per cent).

The collection of data is critical to accurately measure and demonstrate specific health disparities, Anderson said.

Ruth Bonneville / Free Press Dr. Marcia Anderson, vice-dean of Indigenous Health at the University of Manitoba’s Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, discusses findings of race and equity in the health-care system data at the Legislative Building, Tuesday.

The report says there are more low-acuity emergency department visits by Indigenous patients compared to their population size in Manitoba, but that doesn’t mean they’re “frequent flyers” who use ERs inappropriately, she said.

It may reflect gaps in health care and lower access to other forms of care, such as family doctors, that result in more ER visits, she said.

“Unfortunately, in a system under stress, it is often those who are the most marginalized and have the fewest resources who are impacted the most,” Anderson said.

The percentage of patients, meanwhile, who presented as the most ill and triaged with higher acuity were similar across the board.

Anderson said what surprised her in the findings was that the vast majority of patients who leave against medical advice are Indigenous — 63.5 per cent. Those who leave without being seen, including patients triaged with a higher acuity, are most often Indigenous.

“I think what that points to, for us, is there is more work to be done and more supports we can offer ensuring the building of a positive therapeutic environment and accessing the strength of all members of the health-care team and supporting each patient who needs the health care that we can receive,” Anderson said.

“That would be a priority for me — to see some of those numbers coming down.”

Asagwara said people who deliver care also experience racism, which can contribute to burnout.

“As a black nurse, I’ve felt systemic racism,” the health minister, a registered psychiatric nurse, said. “Those working on the front lines should not be blamed for this. We all participate in it.”

The findings released Tuesday are not unique to Manitoba, Asagwara said. The systemic failure to provide adequate care to an increasingly racially diverse population is a national issue that the province is committed to addressing, the minister said.

The collection of race and ethnicity data is a response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action No. 19 — for governments to identify and close the gaps in health-care outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. A steering committee is helping design steps to eliminate racism in the health-care system, with training for students and staff.

The report’s highlights “all seem consistent with the anecdotal evidence that we have been hearing for a very long time,” said lawyer Vilko Zbogar, who represented the family of Brian Sinclair in a civil case after he died in 2008 at the HSC emergency department.

Sinclair, a 45-year-old Indigenous man and double-amputee who used a wheelchair, sat for 34 hours in the waiting room without being questioned or treated by hospital staff. Zbogar said he hadn’t had a chance to read the full report Tuesday, but knows racism is still a concern in health care.

“Indeed I am now representing another Indigenous man — Justin Flett — who was triaged as a 5 (the lowest acuity) when he had life-threatening appendicitis and was discharged from a hospital in The Pas without being properly diagnosed, leading to his harrowing journey to Winnipeg to seek life-saving surgery,” Zbogar said in an email.

Flett, a Tataskweyak Cree Nation man who lives in Winnipeg, filed a lawsuit following the 2023 incident naming the Northern Health Region, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority and a doctor at The Pas hospital as defendants. The doctor has since filed a statement of defence.

— with files from Scott Billeck

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

Carol Sanders

Legislature reporter

Carol Sanders is a reporter at the Free Press legislature bureau. The former general assignment reporter and copy editor joined the paper in 1997. Read more about Carol.

Every piece of reporting Carol produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, June 18, 2025 11:28 AM CDT: Adds chart from report, clarifies Manitoba average is for all ages and facilities.