Magellan, U of M team up for satellite monitoring project

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/10/2024 (409 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Satellites and other items are increasingly being launched into space — and with them, the risk of “catastrophic” collisions is growing.

Enter the University of Manitoba and Magellan Aerospace. The partners, alongside Canadian and United Kingdom governments, are building two satellites to monitor objects in space over Canada and the South Pole.

Private companies, militaries and researchers are more commonly sending their property beyond earth’s bounds, noted Philip Ferguson, lead of the University of Manitoba’s space technology and advanced research laboratory.

Collisions between satellites and other items “are, of course, catastrophic because of the incredible velocity involved,” Ferguson said.

Tiny pieces of debris left behind are as destructive as bigger components, he added: “It’s like many, many bullets being shot at a spacecraft.”

The leftover debris — not visible from the Earth — can persist for centuries.

Defence Research and Development Canada, a branch of the country’s Defence Department, didn’t provide numbers about near-collisions by print deadline.

Anecdotally, they’ve been increasing, Ferguson said.

He’s been involved in past satellite projects; he’s been notified by the government of collision threats and his team has acted to reroute.

Between Dec. 20, 2023, and May, about 36,000 space objects flew in low earth orbit, the Canadian Space Agency’s space program policy vice-president told Global News.

Collisions aren’t common, Ferguson underlined.

Still, the increase in satellites requires “more vigilant observations” for continued safety, according to Paul Harrison, a project manager at Magellan.

The aerospace company has a long-standing partnership with Ferguson and the U of M. Last year, the duo collaborated with other schools to send a satellite to the International Space Station.

The pair used the satellite’s design while bidding for this latest project: Defence Research and Development Canada sought organizations to build a spacecraft system tracking objects over the South Pole.

“(We) fit the bill,” Ferguson said.

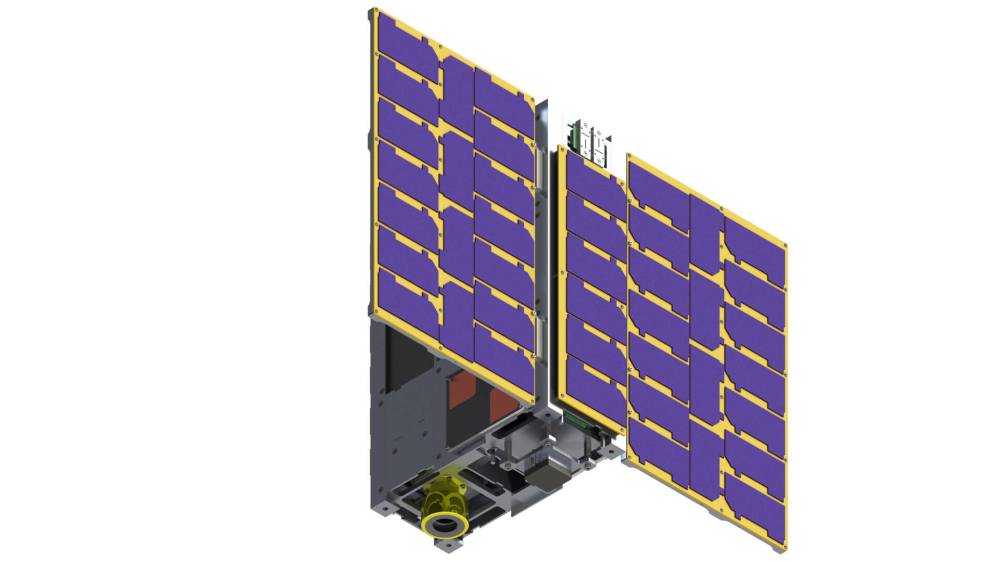

A team from Magellan is creating a satellite called Redwing, estimated to be the size of a large suitcase.

University of Manitoba students and faculty — about 25 people overall — are working on the Little Innovator in Space Situational Awareness (LISSA). A shoebox should be similar in size.

The two organizations will work closely together. If all goes as planned, the satellites will launch together in 2027; eventually, LISSA will trail Redwing.

They’ll follow a polar orbit, trekking over the North Pole, then the South Pole, then North Pole again. A single orbit around the world should last 90 minutes, according to Ferguson.

He wouldn’t detail the machines’ sensors — much of the project is confidential — but LISSA will be equipped with a short-wave infrared camera to assist with capturing images in the Antarctic.

“We will see many, many orbits of … spacecraft and many different passes of the South Pole,” Ferguson said. “Understanding where spacecraft are and where they will be five minutes, 10 minutes … from now is very important.”

There’s a chance the satellites will spot spacecraft from other countries’ militaries Canada wasn’t previously aware of. The objective is to track all that’s around and prevent collisions, Ferguson reiterated.

The satellites will orbit the world for “several years,” using batteries rechargeable via solar power.

Data from Redwing and LISSA will be analyzed by Defence Research and Development and the United Kingdom’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl).

LISSA’s short-wave infrared camera is slated to come from the U.K.

“The collaboration with our Canadian partners will enable us to improve the characterisation of objects and maintain security in space to protect our mutual interests,” Gemma Bagheri, Dstl space research and development program manager, said in a news release.

Canada’s Department of National Defence provided $900,000 for the addition of LISSA to the project this April; initially, the plan was just for Redwing.

The U of M is receiving roughly $750,000 for its contributions.

Magellan announced it was awarded a $15.8 million Redwing contract in March 2023. The Redwing microsatellite is a new variant of Magellan’s previous satellite designs.

The Redwing will provide near real-time communications, according to Harrison.

Magellan plans to operate both satellites with support from the University of Manitoba. Communications will run through ground antenna stations owned by C-Core in the Northwest Territories and Newfoundland and Labrador.

ABB Inc. and Toronto-based York University are also partnering on Redwing.

Ferguson called it “the best feeling in the world” to have roughly 15 students working on LISSA. The partnership between Magellan and the post-secondary helps to build the talent pool the industry relies upon, Harrison added via email.

gabrielle.piche@winnipegfreepress.com

Gabrielle Piché reports on business for the Free Press. She interned at the Free Press and worked for its sister outlet, Canstar Community News, before entering the business beat in 2021. Read more about Gabrielle.

Every piece of reporting Gabrielle produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.