Blast from the past Fifty years later, questions linger about Kenora bank robbery explosion

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/05/2023 (947 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

KENORA, Ont. — Joe Ralko spent a day in May 1973 cleaning bits of human flesh out of his typewriter at the Kenora Calendar office.

The 19-year-old Grade 13 student at Lakewood High School had a junior reporting job at the weekly newspaper above the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce on Main Street in the northwestern Ontario city. An incident on May 10, 1973 — the day before he set to work cleaning — blew in all the windows at the Calendar. Shards of glass flew into the office, along with bits of flesh and blood from a bank robber whose caper had gone seriously and shockingly wrong.

Ralko’s Underwood typewriter sat under a street-side window and took the brunt of the debris. Ralko estimated the 10-kg machine had a cup of flesh pushed deep into the mechanism of keys, lettered arms and ink reels. He cleaned it using tissue paper, toilet paper, rags and his bare fingers, all the while breathing through his mouth in an office that reeked of “burning flesh and gunpowder,” he said in an interview this month.

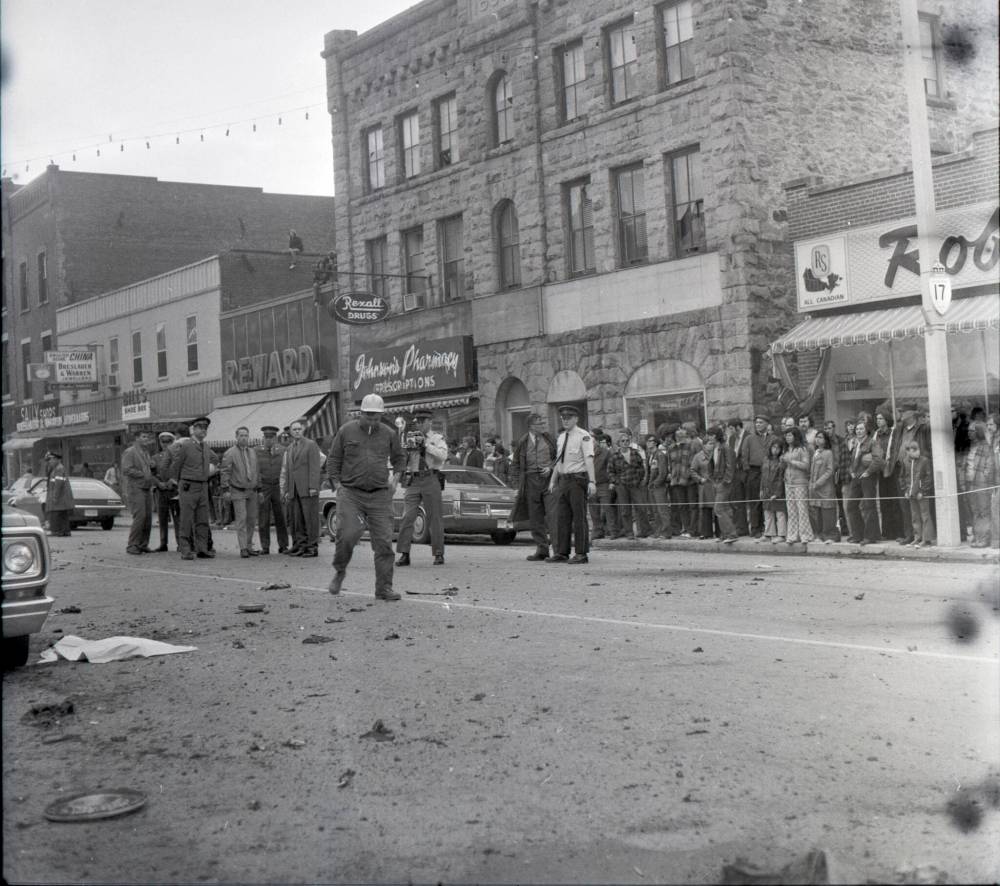

The robbery ended with a blast at 4:12 p.m. on May 10, 1973. Fifty years later, the people of Kenora are still wondering who the culprit was and why he chose Kenora.

Residents got wind of a bank robbery in process just before 3 p.m. that day. A man had entered CIBC bank manager Al Reid’s office a few minutes earlier. The man wore a fedora and a faded pink and grey plaid jacket — an unusual version of the red-and-black plaid item locals call a Kenora dinner jacket. He was carrying duffle bags and a couple of guns.

The man told Reid he wanted money, and to call the police and let them know. He also told Reid to get everyone out of the bank. While people streamed out, and while the police double-parked outside the bank manager’s street-side window, the robber pulled a black stocking over his head and put a dead man’s switch in his mouth.

A dead man’s switch is designed to close the circuit and detonate a bomb if the person keeping the switch open is incapacitated, injured or killed. The robber’s switch was a clothespin with wires on each pad. At the other end were six sticks of dynamite in one of the robber’s bags. If the pin closed, and the pads came together while the safety was off, the bomb would explode.

The robber kept the switch open with his teeth. He made sure each police officer had a good look at the dynamite wired to the switch. Heeding the authority of a walking bomb, police and Reid loaded cash from teller wickets and vaults into the robber’s bags.

While the gathering of cash proceeded inside the bank, the town was in a frenzy. Reporters from the CJRL radio station across the street were at the windows giving live reports. They told people to stay away, but curious residents couldn’t help themselves. Between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m., an estimated 1,000 people gathered on the sidewalks and behind police barricades at each end of the block. One Lakewood student on the scene was Ralko, who took up a spot 10 metres from a rifle-bearing police officer and 20 metres from the CIBC’s front door.

Ralko is a career journalist and author based in Regina. In 2017, he published The Devil’s Gap: The Untold Story of Canada’s First Suicide Bomber.

In his book, Ralko pieced together as much as he could about the two weeks leading up to May 10. A stocky, red-haired stranger arrived by train and checked into the Kenricia Hotel, the big brick icon still standing at the corner of Main and Second streets. He arrived at the hotel with a trunk with “Paul Higgins” stencilled on it, checked in under that name and gave a Toronto address. Ralko gathered first-hand accounts and pieced together how the mystery man investigated downtown Kenora, left for a few days — perhaps to join a work camp, where he could access dynamite — and then returned to the hotel.

At 3:30 p.m. on May 10, about 40 minutes into his caper, the robber asked for a vehicle, a driver and safe exit out of town. Const. Don Milliard of the Kenora Police Service volunteered to drive and changed into civilian clothes to appear less conspicuous. The getaway vehicle was a green Dodge pickup with “Town of Kenora” stamped on the door. Milliard and the robber exited the bank at 4:12 p.m., and it was all over within a minute.

50 years later

Joe Ralko, robbery witness, journalist and author of The Devil’s Gap: The Untold Story of Canada’s First Suicide Bomber, will be making a presentation on the infamous caper Wednesday night in Kenora. The event will be at The Muse, beginning at 6:30 p.m.

Milliard, recounting the experience to journalists, said he didn’t want to get into a vehicle with a human bomb, so he scampered around the truck to get some distance from the robber. In that second, Sgt. Robert Letain, the Kenora police officer crouched near Ralko, shot the robber in the chest. Ralko hit the ground.

The dead man’s switch slipped free, and the dynamite exploded. The robber was killed instantly. Milliard was thrown about 10 metres, and his pants were blown off. Reports suggested the money bag Milliard carried on his back saved his life. The blast blew out windows up and down the street. Smoke filled the air, and money flew all over the place. About a dozen people suffered cuts. Nobody except for the robber died.

In the hours after the blast, police and responsible citizens gathered up most of the cash and returned it to the bank. Some of the bills were scorched and stained with blood. The bank claimed at least $10,000 had been stolen, but media reports speculated it was much higher, between $50,000 to $100,000. Some of the cash was never recovered.

News reports over the next few days filled in a lot of the details. Stephen Riley, editor of the now-defunct Calendar, interviewed the bank manager the next day. “Mr. Reid said that there was no indication that the man had any specific plans,” Riley wrote, and included a couple of quotes from Reid.

“The impression I got was that he was just playing it by ear,” Reid told Riley. “This is what took so long. After we got the cash, he seemed to hesitate. ‘Where do we go from here?’ sort of thing.”

Reid added, “When I asked him why he was doing this, he said, ‘Oh I just wanted to give Kenora something to talk about.’”

Police investigators went through the robber’s hotel room, finding a map of Quetico Park, which borders the Ontario-Minnesota border to the east. Police also found survival-type food and wilderness gear. The fact he didn’t have any of it with him during the robbery supports Reid’s notion that the robber didn’t have much of a plan.

In his book, Ralko described the robber’s final seconds from Letain’s perspective, suggesting one final fatalistic change of plan. While Milliard was going around the other side of the truck, “Higgins did something strange,” Ralko wrote. “He turned away from Milliard, stepped off the sidewalk between two parked cars and squared himself up facing the barricade at the north end of the block… The robber wasn’t moving. In fact, he was making himself a highly visible target.”

In an interview, Ralko said, “Today, the incident would be called suicide by cop.”

Investigations couldn’t uncover anything about the robber. Paul Higgins was a pseudonym, and his Toronto address didn’t exist.

Today, on a sunny May afternoon, one can take a patio table at Lake of the Woods Brewing Company and drink a New England IPA called Dead Man’s Switch.

“We wanted to pay homage to a unique event in Kenora’s history,” Lake of the Woods Brewing Company president Taras Manzie said.

When asked why they chose that particular name, Manzie said, “You only really see or hear of a dead man’s switch in the movies. It’s just so surreal that we gravitated straight towards it.”

Unfortunately, a few pints don’t provide any more knowledge about who the robber was or why he decided to rob a bank in Kenora.

In 2003, Dan Jorgenson, a Kenora Police Service inspector at the time, came across an envelope of the robber’s red hair clippings in an evidence box.

“I was surprised they took hair samples in the first place. At the time, there was no DNA testing,” Jorgenson was quoted as saying in a May 2003 article in what was then called the Kenora Daily Miner and News.

Without the follicle and skin root, hair contains only mitochondrial DNA — genetic information from the mother’s side.

At that time, the suspect was described as a 45-year-old, “fedora-wearing bearded limping German immigrant with a French wife and brother in Thunder Bay,” the article stated, adding the suspect had been reported missing in British Columbia before the robbery and abandoned a truck in Winnipeg. A hair sample was taken from the man’s brother in Thunder Bay. The Miner and News reported two months later that investigators had found the “missing” man living in France.

Police had no further leads. David Canfield, Kenora’s mayor in 2003, told the Miner and News, “The best thing to happen now is to drop it. I think a lot of us were looking for closure.”

The quest for closure could be renewed with advanced DNA tools.

Nicole Novroski, a forensic geneticist in the forensic science program at the University of Toronto Mississauga, said it might be possible to identify a missing person using new techniques and 50-year-old hair clippings. Traditional DNA analysis is more sensitive and refined, Novroski said. The same DNA sample analyzed today could create more leads than in 2003.

Genetic genealogy, a newer path that taps into family trees, has led to arrests in a few high-profile cold cases over the past few years. Law enforcement used genetic genealogy to identify and arrest the Golden State Killer in a suburb of Sacramento in April 2018. In Canada, police used genetic genealogy in 2020 to solve the 1984 murder of Christine Jessop, a nine-year-old from Queensville, Ont. Guy Paul Morin was wrongfully convicted of her killing and served years in prison before being released.

Success often depends on the quality of the DNA sample. “Rootless hair has notoriously low-level DNA,” Novroski said. “And over time, that DNA will degrade.”

The other challenge, Novroski said, is that “sometimes the closest match is still a distant relative, therefore a lot of additional investigation and genealogical work are required.”

Ontario Provincial Police would not say whether they still have the robber’s hair and would consider new DNA techniques to try to determine the robber’s identity.

“This is still an open investigation,” regional spokeswoman Autumn Eadie said. “We cannot discuss any specific evidence related to investigations, but I can tell you that evidence related to such an open investigation is kept on file.”

The Kenora Police Service disbanded in 2009, and the OPP took over policing duties for the city.

The case is not closed, but this is not a case where a culprit is at large or a victim’s body unidentified. It’s not clear what resources police might be willing to invest.

Novroski sees reason to try. “At the end of the day, this is a cold case without an identity,” she said.

The incident on May 10, 1973, became a cautionary lesson about crowd control during bomb scares. Witnesses would never forget what they saw, heard and smelled at 4:12 p.m. The moment is part of Kenora’s psyche.

Investigators might never be able to answer why the robber chose Kenora, but the “who” door is still open. Perhaps genetic genealogy will find a family that has been wondering for half a century where its red-haired relative went back in 1973.

fpcity@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Thursday, May 11, 2023 9:25 AM CDT: Removes line on high school for clarity