An opportunity to banish barriers, build bridges downtown

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/10/2017 (3000 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

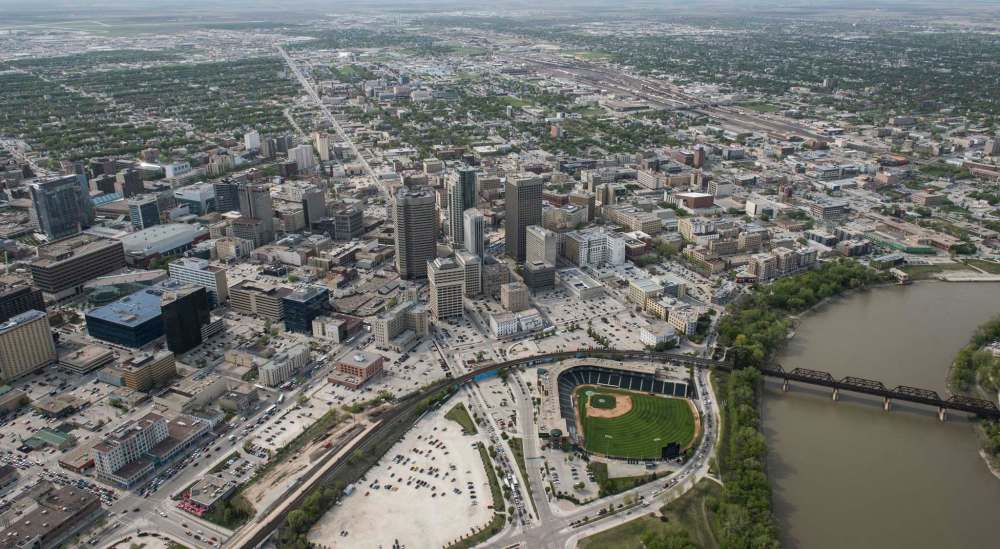

As we get ever-nearer to the removal of the pedestrian barriers at Portage and Main, a nagging question remains.

Is this iconic intersection, and the neighbourhood it anchors, going to be better off after the barriers are gone?

It’s a very difficult question to answer. So difficult, in fact, it may require us to just take a leap of faith and see what reopening the intersection accomplishes. Right now, for every argument in favour of removing the barriers (more friendly to pedestrians, a chance to revive downtown commerce) there are arguments against (delaying vehicular traffic, danger to pedestrians).

Undeterred, Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman has forged ahead with plans to reopen the intersection. To that end, the city produced at report which recommends $3.5 million to take down the barriers, upgrade the underground concourse and make improvements to the plaza in front of the Richardson Building on the northeast corner of the intersection.

For Bowman, this initial expenditure is “a commitment to the heart of our city.” Perhaps, but it’s not really much of a commitment. It’s a rather puny sum of money that will result in little more than the removal of the barriers. And it’s entirely unclear what removing the barriers, on its own, will accomplish.

One thing is fairly certain: even for those who do not think the removal of the barriers will change much about the way downtown works, they create a horrible image. Dark and foreboding, they would appear to be part of a school of architecture along the lines of “brutalist prison.”

On an aesthetic basis alone, removing them is most definitely a good idea. But only if the city has a dynamic vision for what is put in the place of the barriers.

Bowman and many other supporters of a barrier-free intersection see it as the first step to restoring pedestrian flow and reviving commercial activity through the downtown, particularly the Exchange District. Architects and urban planners believe that connectivity — the ability to create free and easy access between areas of a city’s core — is the key to making it more vibrant.

While there should be little debate about value of connectivity, there should be some concern that just removing the barriers will accomplish Winnipeg’s connectivity goals.

It’s important to note the reopening of the intersection will not be accompanied by the closure of Winnipeg Square beneath Portage Avenue and Main Street. The tunnels that run under the intersection may “connect” people to places, but not in a way that encourages street-level activity — which is what Winnipeg’s downtown desperately needs.

As well, for the thousands of people who work in the high-rise buildings that ring the intersection, new pedestrian crosswalks will have little appeal, particularly during the winter months. The creation of that sub-grade mall has spawned generations of Winnipeggers for whom the entirety of their downtown experience is the interior of a parking garage, a tunnel, a downtown shopping mall and an office.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, a reopened Portage and Main does not make a dent in the decades of obtuse urban planning that shifted the focus of city dwellers from the core to the suburbs. Most of the malls, stores and even public amenities central to the lives of Winnipeggers remain located well away from the city’s most iconic intersection. The opportunity to cross above ground seems unlikely to pose much of an appeal for people that feel no need to come downtown now.

These realities emphasize the need to come up with something bigger and bolder than just removing the barriers: something like an elevated pedestrian bridge.

A reader drew my attention to a magnificent elevated pedestrian bridge in Lujiazui, in the Pudong district of Shanghai. It’s a massive structure, with a deck wide enough to accommodate 15 people standing shoulder to shoulder. A magnificently landscaped traffic circle keeps the traffic moving through the intersection while pedestrians can observe from above.

The Lujiazui span is hardly alone; similar bridges have been built all over the world.

The Rzeszow regional office and pedestrian bridge in Poland is smaller, but striking because of its longer, gently sloped stairs and ramps.

The Hovenring — a pedestrian and cyclist bridge in the North Brabant province of the Netherlands — features a broad, circular deck dramatically suspended from cables connected to a enormous spire. The bridge over the Segunda Circular in Lisbon, Portugal, takes an even wilder approach, with a criss-cross of striking orange steel spans allowing pedestrians and cyclists to cross a busy highway.

In all these examples, urban communities opted to kill two design birds with one stone: improved connectivity through the movement of people over a busy intersection without crippling vehicular traffic; and the creation of a bona fide attraction.

It is possible a bridge over Portage and Main will not accomplish all of the connectivity goals proponents believe to be at the heart of the campaign to remove the pedestrian barriers. It is certainly true the shortest point between two distances is a straight line across the intersection, not up and over, or down and underneath.

But it would be something to see. And perhaps it would do something removing the barriers alone will not: inject some excitement into a downtown still somewhat short of critical mass.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Dan Lett is a columnist for the Free Press, providing opinion and commentary on politics in Winnipeg and beyond. Born and raised in Toronto, Dan joined the Free Press in 1986. Read more about Dan.

Dan’s columns are built on facts and reactions, but offer his personal views through arguments and analysis. The Free Press’ editing team reviews Dan’s columns before they are posted online or published in print — part of the our tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.