Courage and conviction

Advocating for those who were discriminated against came naturally to Winnipeg mother

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/08/2018 (2602 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The new $10 bill features Viola Desmond on one side and the Canadian Museum for Human Rights on the other, but that isn’t the only connection the late human rights activist has to Winnipeg.

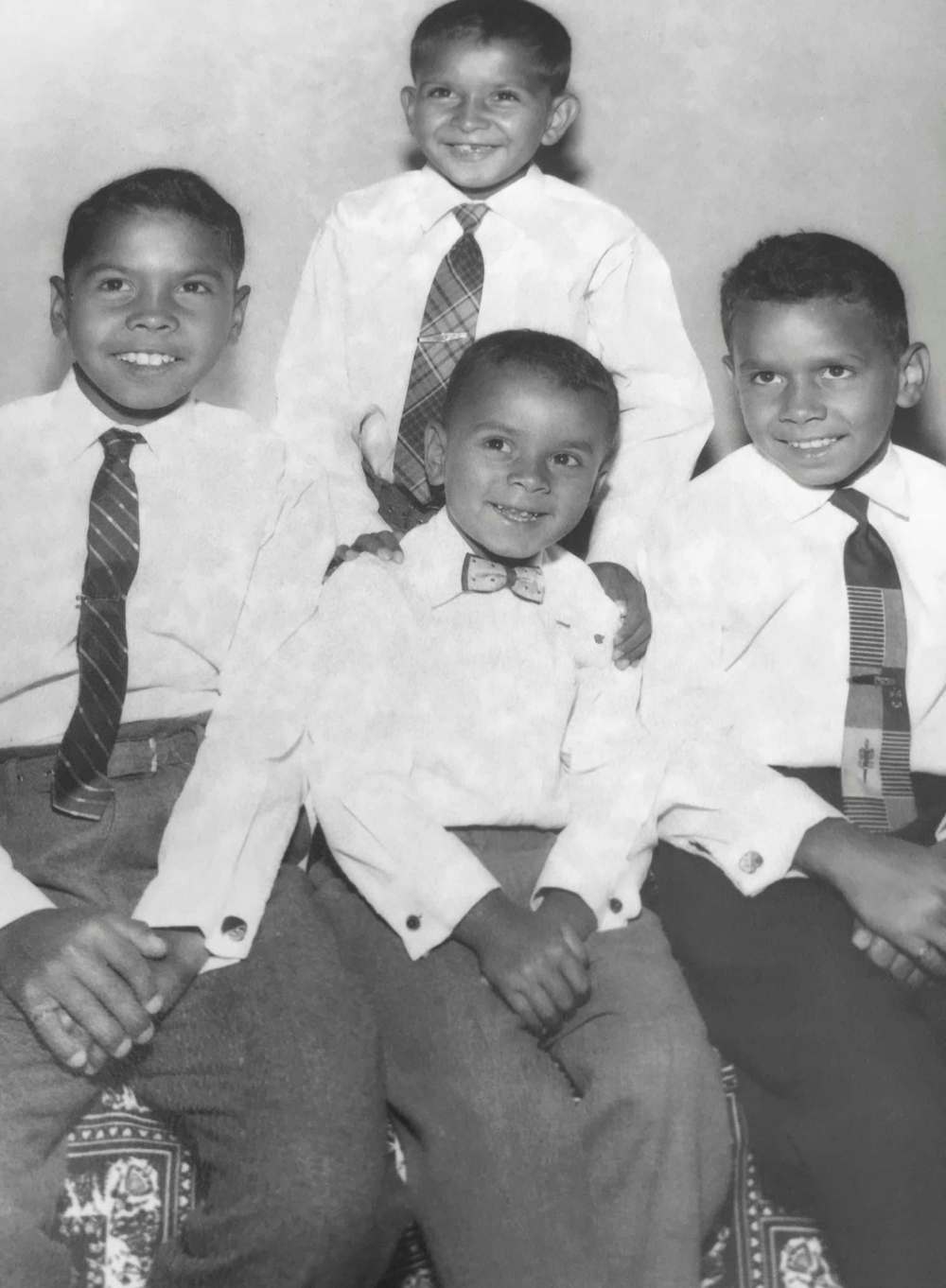

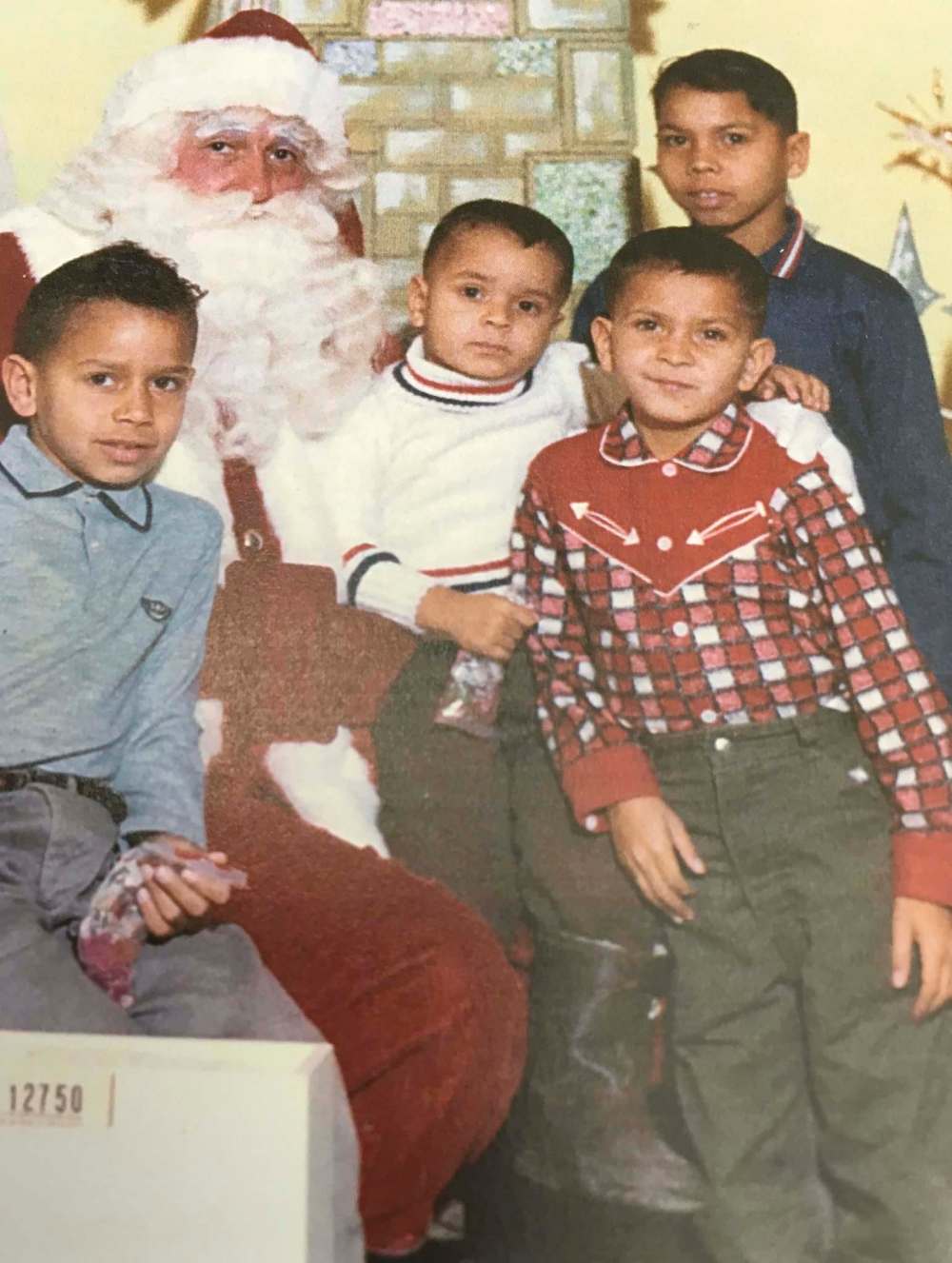

Thousands of miles from New Glasgow, N.S., where Viola Desmond refused to give up her seat in a whites-only section of a movie theatre in 1946, Audrey Desmond was challenging discrimination in 1950s and ‘60s Winnipeg, where she and her husband were raising their four biracial sons.

In 1952, a Caucasian woman named Audrey Read, married Henry Desmond, an athletic army veteran from Nova Scotia who came to Winnipeg for his work with CN Rail.

His aunt was Viola Desmond, who launched the first known legal challenge against racial segregation brought forth by a black woman in Canada after she was forcibly removed from the theatre and jailed overnight.

In Winnipeg, Audrey Desmond made it her mission to stand up for people who were being singled out for being different, whether it was her own biracial sons or someone who was physically challenged, said her eldest child and Viola Desmond’s great-nephew, Sterling Desmond.

“Coming from an interracial marriage, she would always stand up if someone made a disparaging comment. She was that way. She had to stand up,” said the doctor who was raised in Winnipeg and practises natural medicine in Comox, B.C. His three younger brothers — Terry, a retired police officer and Lindsay and Jamie who are both school division employees — live in Winnipeg and asked him to speak about their mom. She died in May at age 83.

Long before there was anti-racism education or a human rights code, the Winnipeg woman in her own direct and low-key way was schooling those who needed to learn a lesson.

“She was very protective of her four boys,” Sterling said.

“When I was in school in the 1950s… Canada was a fairly good melting pot,” he said. “But, at the same time you would find people who were very ignorant and discriminatory in the way they would treat someone who was not a Caucasian,” he said. “There were a few incidents where mom would have to come to school and rebuke someone for being discriminatory. She was never afraid to stand up to someone in authority,” said Sterling, recalling one incident at his school.

“There was a science teacher who should not have been a science teacher. He would put me down and there was no rationale for how I was being treated except for him being discriminatory. My mom had to pay him a visit,” he said.

“It would help,” Sterling said.

It set an example for him and his brothers and anyone who witnessed Audrey in action, he said.

“You learned right away to be courageous and to stand up and not take something lying down. You learned to speak out about it immediately. She taught valuable lessons right away.”

Audrey was 18 when she met her husband-to-be Henry at a dance in Winnipeg.

“They had a really good bond,” said Sterling, whose father died in 1993. “They were both very caring people but very courageous, too. To have an inter-racial marriage at that time you had to have a lot of courage.” Henry uprooted himself from the Maritimes and moved to the Prairies. Audrey lost her mother when she was still a child. “Her father took her out of school in Grade 9 to look after the household. She had to grow up fast and deal with life,” he said.

“My mom was a very stoic person and very courageous in that she kept picking herself up and trying to find the best in life,” he said. That included marrying Henry, the love of her life, at time when “mixed marriages” were frowned upon.

“Mom had to deal with racism — even with her dad,” said Sterling. He had a hard time accepting his daughter’s biracial marriage until after his second grandson was born, said first-born Sterling.

As kids, they didn’t learn about their great-aunt Viola Desmond until their mom told them about her when they were adults. In 2012, Viola Desmond was honoured on a Canada Post stamp and Audrey shared the good news with her church congregation.

Earlier this year, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg celebrated Viola Desmond and the new $10 bill that displays both their images.

“She always wanted to get to the museum to see it, but I don’t think she ever did,” said Audrey’s best friend, Dorothy Kizuk. They talked about going but illness and mobility issues prevented them from getting to see the homage to Viola Desmond, someone whom her friend revered. “She was very proud of her, that’s for sure,” said Kizuk. “She sure thought a lot of her.”

Audrey didn’t talk about her own struggles with discrimination, said Kizuk who became friends with her after Henry died. They worked in the Free Press circulation department on Carlton Street before moving to the new building on Mountain Avenue, where Audrey worked until she retired at age 75.

“She cared about everybody,” said Kizuk. And she had an adventurous spirit, said her travelling companion, who visited Vegas with her more than once. The pair of landlubbers decided to go on a cruise together, even though Kizuk was afraid of the water.

“We were both terrified of it but everybody was talking about cruises,” said Kizuk. Facing her fear with her friend was a lot of fun, Kizuk remembered.

“Audrey was so loveable.”

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

Carol Sanders

Legislature reporter

Carol Sanders is a reporter at the Free Press legislature bureau. The former general assignment reporter and copy editor joined the paper in 1997. Read more about Carol.

Every piece of reporting Carol produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.