Edward Darbey, taxidermy and the last buffaloes

Winnipeg shop's clientele included sportsmen, naturalists and scientists

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/01/2020 (2134 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

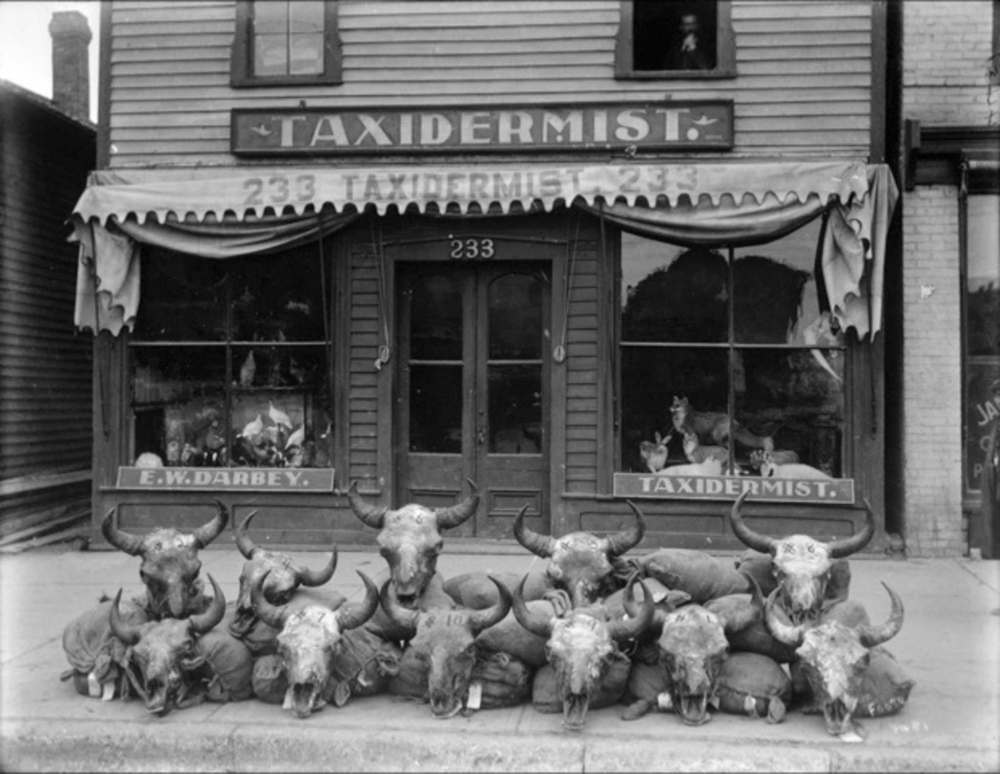

This truly historic image was taken in November 1911 by Winnipeg photographer Lewis Benjamin Foote. Its most intriguing feature is the bizarre, mildly humorous array of gristly, numbered “buffalo” skulls in the foreground.

The backstory pivots on the fact that bison were extinct in Canada by 1900. Possibly motivated by a conservation ethic, the Canadian government bought 716 bison between 1907 and 1912 from Michel Pablo, a Montana entrepreneur who, with partner Charles Allard, had bred the animals to generate lucrative sales to museums and parks.

Most of the 716 reached Alberta game reserves, but a small number were too wild and were simply shot. At a 1911 Winnipeg auction, 13 of Pablo’s untamable bison — billed as the last “wild” relics of the 50-60 million monarchs of the Prairies — were sold for robes and head mounts. They likely arrived in Winnipeg in the summer of 1911 (note the snowless sidewalk and open window in the photo).

Their carcasses would have been skinned and the hides salted and/or frozen; the skulls were numbered to facilitate reuniting respective skulls and capes before mounting by taxidermist Edward Darbey. Prepared for auction on Nov. 25, the heads sold for $500-$800 each, making fine wall trophies for 11 Winnipeg bidders.

The Victorian British notion of “decorating” homes with “stuffed animals” had its heyday among sportsmen and the well-to-do of Canadian society, too. However, by around 1890, the notion was butting heads with the nascent conservation movement. Yet, the federal and provincial governments needed immigrants to settle and tame Canada’s vast, rich, untrammelled West. Stuffed, mounted wildlife was considered symbolic of the North West Territory’s “superabundance,” and thus integral to strategies for attracting immigrants to Canada. Taxidermy displays were featured at provincial, national and international exhibitions, and taxidermists were kept busy supplying mounts. By about 1902, George Atkinson, Alex Calder, Edward Darbey, George Grieve, Abel Hine and his three sons, and William White were noted Winnipeg taxidermists, all with shops on Main Street. Winnipeggers eagerly attended these shops and exhibitions because, until 1932, the city had no permanent public museum to exhibit natural history specimens.

As a 15-year-old, Edward Wade Darbey came to Winnipeg in 1887 from Ontario with his parents and four siblings, and soon found work with William Fenwick White, noted dealer in Indian curios. In 1898, Darbey purchased George Grieve’s taxidermy at 247 Main St., which around 1903 shifted to 233 Main, where he further honed his talents in taxidermy and curio collecting. He also sold raw hides, buckskins, moccasins and snowshoes, many made by Cree artisans.

Darbey’s shop is characterized by clapboard construction, poor-quality window glass imperfectly reflecting buildings on the west side of Main Street just north of St. Mary Avenue, awnings to protect the window displays from the sun’s bleaching rays and a remarkable menagerie within.

Several animals are exotic for Winnipeg, like the two white-coat seal pups (right-hand window), surrounded by snowshoe hare, red fox, badger, swift fox, ermine and a squirrel, all overseen by an exotic walrus skull. The left-hand window is cluttered, but when magnified the image reveals two grouse (spruce and ruffed) above a diorama with three (four?) white-tailed ptarmigan in winter plumage. A magpie swoops down in front. Others are indistinct: possibly a blue jay, owls and a wasp nest. At the open window, upper right, blurry, a man leans on his elbow; is this a “Hitchcockian” cameo of Darbey himself?

Darbey already had the distinction of appointment by premier Rodmond Roblin as “official taxidermist to the Manitoba government” about 1902. It required him to provide taxidermic mounts to beautify public buildings. Two of his bison mounts long stood guard inside the front entrance of the legislature. The honour bestowed by Roblin, plus Darbey’s fine reputation, convinced collectors far and near to submit specimens, even rare whooping cranes, for taxidermy. The Pablo bison were a bonus!

Clientele included sportsmen, naturalists and scientists, like Cyril Harrold (a remarkable collector and taxidermist who worked briefly for Darbey), Ernest Thompson Seton and William Rowan (later a professor and pioneer in bird migration studies). Darbey’s obituary published in the Manitoba Free Press on Aug. 26, 1922, emphasized the esteem afforded this fur man in whose shop “could be seen Indians and trappers from the great hinterland of the Canadian west (come) to barter their season’s harvest.” It was a hub of activity and good fellowship.

Darbey’s taxidermy shop was gone by 1921, when the building was demolished to make way for construction of “a modern two-storey garage and motor repair shop.” A newspaper story on Feb. 28, 1921, entitled “Main Street Relics to Disappear,” claimed the site was presently occupied by “the oldest buildings in Winnipeg, two of them occupied by Edward W. Darby (sic), taxidermist… The building at 233 Main Street, occupied by Edward Darby (sic), was the first Wesleyan mission in Winnipeg.” These claims about 233 Main St. could not be substantiated by visits to the United Church of Canada and City of Winnipeg Archives.

For pun and prophet, the headline’s triple-entendre about disappearing relics must be appreciated: Edward Darbey, 49, passed away on Aug. 25, 1922, from a heart-related illness, 18 months after that Free Press announcement. His son Verne and daughter Iris survived him, as did his wife, Edith, who operated the taxidermy elsewhere on Main Street and at two Edmonton Street locations until 1931.

Note: To clarify, bison and buffalo are of the same family, but it is believed early explorers to North America referred to bison as buffalo as they were similar in appearance to the water buffalo found in South Asia and Africa. Bison are found in North America and in parts of Europe. Even though the term “buffalo” is a misnomer, it is still used when referring to our bison.

For more information or to become a member of the Manitoba Historical Society, call 204-947-0559 or email: info@mhs.mb.ca. The MHS is on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as manitobahistory.