When righting a wrong, even posthumously, has to come before legal tradition

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

It is often said that justice delayed is justice denied. The people who say that often obviously weren’t thinking about Russell Woodhouse, his family or his friends.

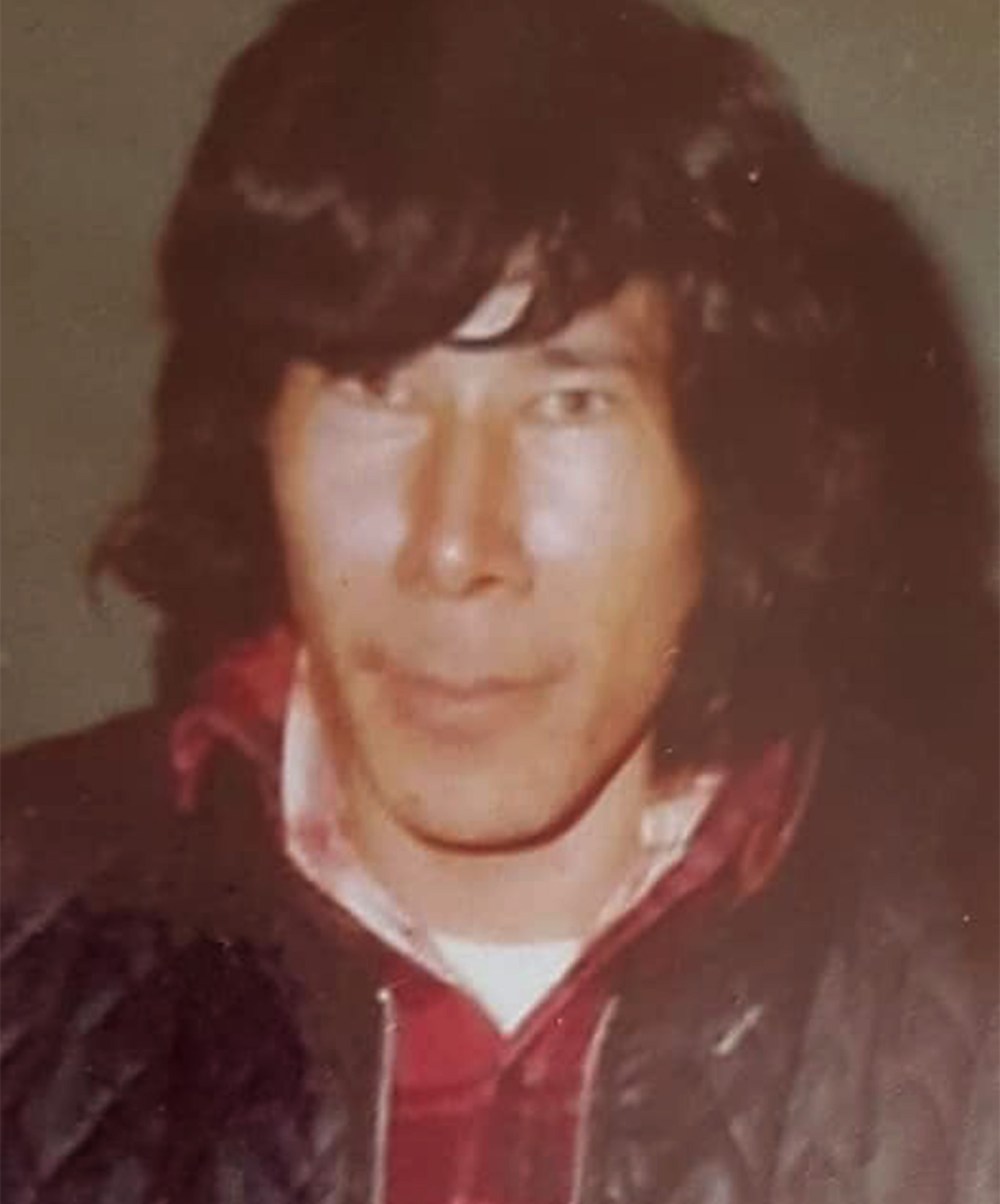

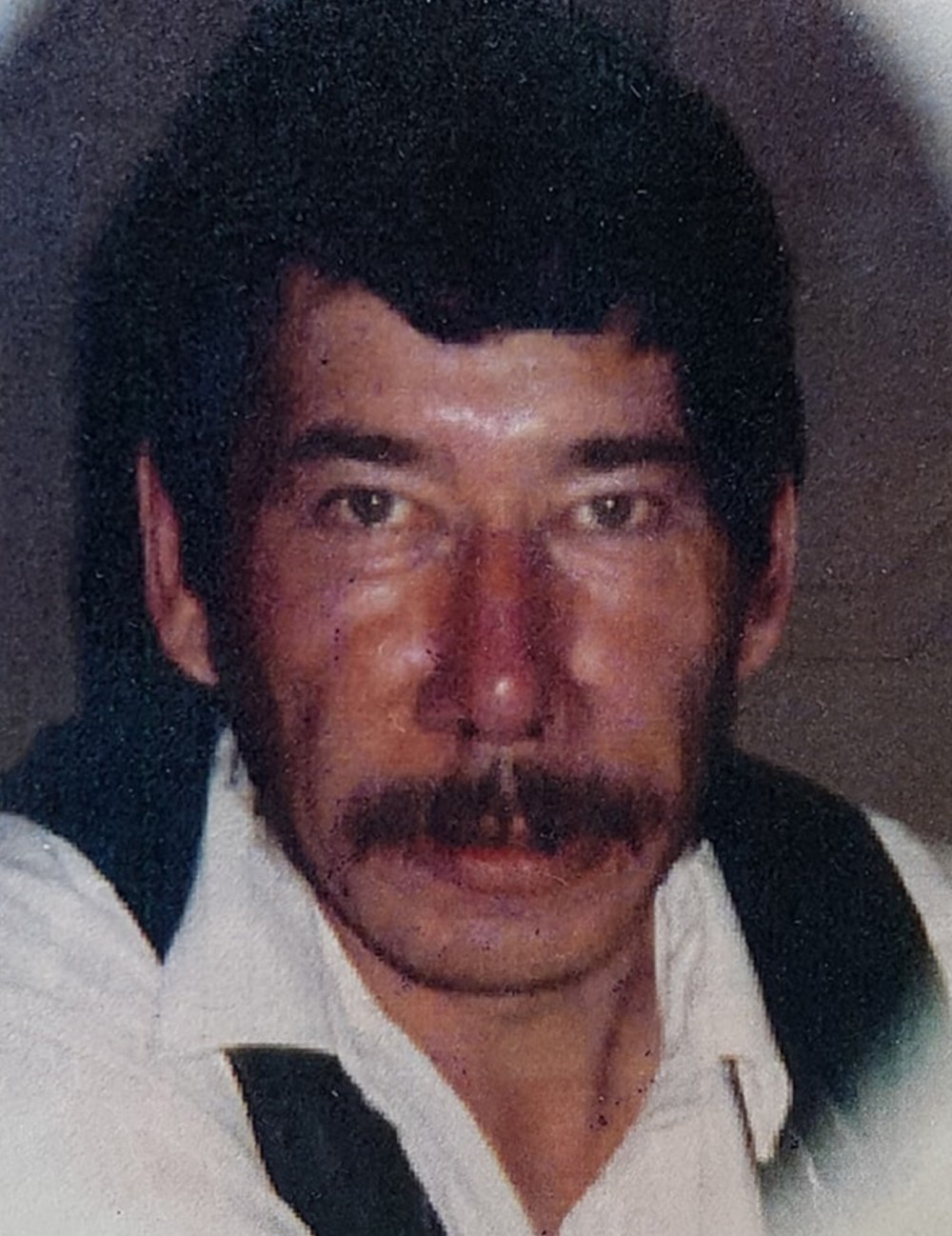

On Monday morning, federal Justice Minister Sean Fraser confirmed he has asked the Manitoba Court of Appeal to review the 1974 murder conviction of Russell Woodhouse, who died in 2011. It’s the first time a federal attorney general has asked for a judicial review after the death of an applicant.

If he were to be found innocent following an appellate court hearing, he could become the fourth man involved in this case to be exonerated.

Co-accused Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse and Clarence Woodhouse were declared innocent in the murder of restaurant worker Ting Fong Chan by the Manitoba Court of King’s Bench. The court’s decision came after a lengthy investigation by Innocence Canada, which helped prove that statements entered at the original trial were fabricated by police.

How important is a posthumous review of a 51-year-old murder conviction?

Important enough that the minister acknowledged Monday he felt obligated to intercede, in large part because Russell Woodhouse’s family never stopped trying to clear his name. They were joined in this relentless effort by Innocence Canada, which did not rest on its laurels for achieving exonerations for the other three accused in this case, and devoted its resources to ensuring Fraser gave full consideration to a posthumous review for Russell Woodhouse.

“This case has been galvanized as one of the most impactful in the history of the legal system’s efforts to remedy wrongful convictions.”

With this most-recent decision from Ottawa, this case has been galvanized as one of the most impactful in the history of the legal system’s efforts to remedy wrongful convictions.

Last year, Court of King’s Bench Chief Justice Glenn Joyal, on a recommendation made by Manitoba Justice, made legal history when he acquitted Anderson, Allan Woodhouse and Clarence Woodhouse of the 1974 murder, and declared all three men innocent.

In most reviews of wrongful convictions — even when it is decided the original case was flawed or biased, or exculpatory evidence was withheld from the accused — or even when there is evidence pointing to a more likely suspect — the courts and prosecution services decline to make any finding of innocence.

In some cases, when a miscarriage of justice has been proven, Crown prosecution branches insist on staying the charges against the accused. This practice — which puts the charges into a legal stasis but does not formally withdraw them — has been condemned by the champions of the wrongfully convicted, who have long argued it left the victims of miscarriages of justice living under suspicion for the remainder of their lives.

For the record, this is no idle concern.

For the most part, Canada’s courts and prosecutors have maintained there is a clear line of demarcation between a confirmed case of wrongful conviction and innocence. This argument is rooted in the English common law tradition that accused persons are ultimately found “not guilty” rather than “innocent” in a court proceeding. Some justice system officials have gone as far as to argue that based on that principle, there is no way to prove “legal innocence” in any proceeding.

Lawyers for Innocence Canada and leading academics who have studied the phenomenon of wrongful convictions have strenuously objected to the argument. They have argued, in turn, that once it has been shown the justice system failed an accused person — either by errors of omission or commission — it is legally unjust to continue to hold that person is state of legal limbo.

If the initial investigation and prosecution were corrupt or incompetent, the advocates have argued, then it is appropriate to issue a finding of innocence.

The advocates who have put forward these arguments are fuelled in this battle by the experiences of some of Canada’s most famous victims of wrongful conviction. The late David Milgaard, Thomas Sophonow and James Driskell — all clearly the victims of miscarriages of justice — have all complained about being subject to decades of ongoing suspicion and abuse from officials in the justice system.

Even in the Milgaard case, where DNA analysis proved that another man was guilty of the murder for which he was originally convicted, justice officials in Saskatchewan continued to assert that scientific evidence proving the involvement of another man was not necessarily evidence of Milgaard’s innocence.

“It would be a shame if Manitoba’s highest court rested on tradition and denied Russell Woodhouse’s family the same clear and unambiguous verdict.”

Right up until the day he died in 2022, Milgaard felt that police and prosecutors in Saskatchewan had never truly acknowledged his innocence or the mistakes that were made in framing him for murder. And for good reason; Serge Kajawa, Saskatchewan’s director of prosecutions when the case was originally tried, famously said that “it doesn’t matter if Milgaard is innocent… his case should remain closed.”

Although the odds are good that the Court of Appeal will add Russell Woodhouse’s name to the growing list of the wrongfully convicted, it is unclear whether it will be willing to go as far as Joyal did in the Court of King’s Bench. It would be a shame if Manitoba’s highest court rested on tradition and denied Russell Woodhouse’s family the same clear and unambiguous verdict.

Russell Woodhouse should be acquitted, and he should be declared innocent. And no amount of legal tradition should change that.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Dan Lett is a columnist for the Free Press, providing opinion and commentary on politics in Winnipeg and beyond. Born and raised in Toronto, Dan joined the Free Press in 1986. Read more about Dan.

Dan’s columns are built on facts and reactions, but offer his personal views through arguments and analysis. The Free Press’ editing team reviews Dan’s columns before they are posted online or published in print — part of the our tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, September 29, 2025 3:43 PM CDT: Corrects typo in headline

Updated on Monday, September 29, 2025 4:07 PM CDT: Adds photos