Still waiting to take off

New facility, same passenger loads — when will Richardson airport take off?

By: Bartley Kives Posted: Last Modified:Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/11/2014 (4105 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

So it’s -29 C in November and you’re thinking this just may be the winter in which you must escape sub-Arctic Winnipeg for somewhere a little less frigid.

Your available time is limited. You need a direct flight from here to make this work.

Happily, there are 17 non-stop flights from Richardson International Airport to warmer American, Mexican and Caribbean destinations — an ensemble of convenient getaways that has grown in recent years.

Toronto tops, by far

Busiest Canadian airports, by passengers in 2013:

1. Toronto Pearson: 36.2 million

2. Vancouver: 17.9 million

3. Calgary: 14.3 million

5. Montreal Trudeau: 14.1 million

6. Edmonton: 6.98 million

7. Ottawa: 4.58 million

8. Halifax: 3.59 million

9. Winnipeg: 3.48 million

10. Toronto Billy Bishop: 2.5 million

11. Victoria: 1.56 million

12. St. John’s: 1.51 million

13. Kelowna: 1.50 million

14. Quebec City: 1.48 million

15. Saskatoon: 1.39 million

16. Regina: 1.23 million

— sources: Airport authority websites

But let’s say you’re not a sun-seeker. You’re an ordinary business traveller, just trying to get from point A to point B with the least amount of hassle.

Not counting small-carrier service to several Manitoba fly-in First Nations, there’s a total of 39 non-stop flights leaving Winnipeg’s airport.

This is respectable for a geographically isolated city with Canada’s eighth-largest metropolitan area. Winnipeg’s non-stop options are smack in the middle of the range of direct flights out of airports in medium-sized cities across Canada.

When it comes to passenger numbers, Richardson also appears perfectly average. The 3.48 million people who flew in and out of YWG in 2013 allowed this city’s airport to rank as eighth-busiest in Canada for passenger traffic.

That’s slightly down from 2012, the first full year of operations at the new terminal. Winnipeg’s airport set its annual passenger record back in 2007, before the old terminal was demolished to the south of the new César Pelli-designed structure.

MAP: How Richardson stacks up against comparable Canadian and U.S. airports

Can’t see the map above? Try viewing it in a new window.

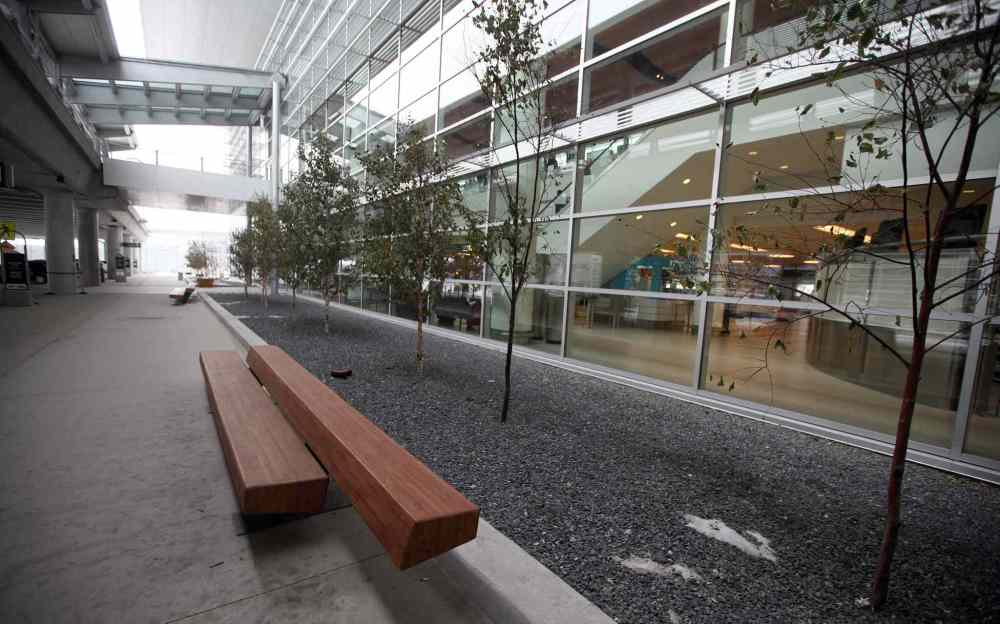

To many visitors, the new terminal is an esthetic improvement upon the 1964 structure beloved by modernist-architecture buffs. To the Winnipeg Airports Authority, the non-profit entity that manages Richardson, the new structure offers more operational efficiencies and room to grow, both in terms of flights and passengers.

But with flat passenger numbers and modest nonstop connection options, the question remains: When will YWG begin to realize the promise of growth afforded by its recent reconstruction?

The new terminal was built as part of an airport expansion pegged at no less than $672 million, including finance charges. The Winnipeg Airports Authority is now carrying $646 million in debt, after borrowing an additional $100 million in 2013 to create what president and CEO Barry Rempel describes as a financial cushion.

The cost of servicing this debt rose to $32.5 million last year, a figure that placed the WAA in the red. It expects to post losses for each of the five next years, thanks to financing charges.

The WAA isn’t in financial trouble, because it has enough cash to cover these interest payments. Last year, the annual airport-improvement fee — a levy added to every outbound ticket — increased to $25 from $20 to raise a total of $34.2 million from Richardson passengers.

In other words, the WAA has spent hundreds of million of dollars to create a new facility that currently serves a similar number of passengers as the old airport, heading towards a similar number of destinations.

So why did we build this thing?

“A new building is not going to bring another passenger. It’s the market that dictates how many people are coming,” explained Rempel last week.

“We’re hampered by geography. We’re a long way from anywhere. The size of the market we have dictates an 80-passenger airplane.

A modest rise

Total passengers at Richardson International Airport over the past decade:

2014 (through end of June): 1.78 million

2013: 3.48 million

2012: 3.54 million*

2011: 3.39 million

2010: 3.37 million

2009: 3.38 million**

2008: 3.57 million

2007: 3.57 million***

2006: 3.39 million

2005: 3.23 million

* First full year of operations for Winnipeg’s new terminal, which opened in Oct. 30, 2011.

** First full year of the global economic recession, which began in 2008.

*** Record to date. Total passengers in 2007 was 3,570,673. There were 640 fewer in 2008.

— source: Winnipeg Airports Authority

“Can those airplanes make the kinds of distances that we need to get (direct) service out of here? In most cases, the answer is no, because those airplanes are designed for shorter-haul kinds of markets.”

Winnipeg’s airport wasn’t expanded to meet passenger-travel needs in the short term. But the WAA expects passenger numbers will rise modestly over the long term, to six million by 2033, and this required the capacity to serve more planes in the future.

“A lot of people would say, ‘Why did we build this massive terminal?’ People question large capital projects. Whether it’s a sports stadium or an airport, they say it’s a waste of money,” said David Duval, director of the Transport Institute at the Asper School Business.

“Well, the airport is basically a point of call when people first come to Winnipeg. It’s not a bad idea to look 20 or 30 years in the future and ask whether it will meet our needs.”

The new terminal is what Rempel calls “rightsized” in that its capacity to handle airplane movements — the arrivals and departures — only slightly exceeds the current demand. Building too much more of an airport would have saddled the WAA with more debt and passengers with even higher airport-improvement fees.

But the airport does plan to expand its terminal on either side, possibly using some of the $100 million in additional funds borrowed last year. Lower-profile extensions would serve smaller aircraft, allowing more room on the main “bridge” for larger aircraft — including those serving more destinations.

Rempel said the new terminal was designed to make it easier for new carriers to enter the Winnipeg market.

Bringing more direct flights to Winnipeg, however, is no simple task — and not just because of the city’s relative isolation and population.

Canada’s two largest airlines, Air Canada and WestJet, generally operate on a “hub and spoke” model, where a handful of major airports — Toronto, Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver — serve as the hub of a wheel of routes.

The spokes lead out to secondary markets, including cities such as Winnipeg. The economics involved, where the airlines want passengers to move through the hubs, serve as a disincentive for direct connections between some of those secondary markets.

This is why three of the top 25 destinations for airline passengers leaving Winnipeg — Victoria, Halifax and Kelowna — are not served by direct flights.

“Halifax deserves non-stop service from Winnipeg. But Air Canada won’t do it. That’s a strategic decision, and I respect that. They have to do what they have to do,” said Rempel, who spent 26 years with Pacific Western, Canadian and Air Canada before joining the WAA.

“But it makes it extremely difficult for anyone else to come in and say ‘Well, I’ll go non-stop’ because of Air Canada’s significant capacity to really take the price down.”

The prospect of Canadian airlines providing direct service between Winnipeg and Halifax, Kelowna or Victoria is poor unless a new ultra-low-cost carrier shows up in Canada and tries to operate under the alternative, “point to point” model. A pair of companies are currently exploring the idea.

For Winnipeggers, the most familiar example of an ultra-low-cost, point-to-point carrier would be Allegiant, the U.S. airline that flies out of Grand Forks and Fargo to vacation destinations, taking many Manitoban passengers.

Among the top 25 destinations for Winnipeg air travellers, only two others are not served by non-stop flights from YWG: New York City and Manila, the capital of the Philippines.

It appears the number of Winnipeggers who travel to New York every year would merit a direct connection, WAA data show. The question is what airline.

It’s unlikely either Delta or United, hub-and-spoke carriers that fly from Winnipeg to Minneapolis and Chicago, respectively, would threaten the viability of their existing routes, especially as these Midwestern U.S. cities are not the ultimate destination for most of the passengers originating in Manitoba.

Since airlines operate on narrow profit margins and utilize as few aircraft as possible, the addition of a new route often means the subtraction of an existing one.

“If we were to get another flight from United, it would be at the expense of another city,” Rempel said.

He cites Manila as a more likely new international destination — or at least the impetus for adding a direct flight from Winnipeg to Hawaii.

The presence of a large Filipino community that travels often to visit relatives encouraged Philippine Airlines to study the idea of a Winnipeg-Honululu-Manila flight, Rempel said.

That didn’t translate into an actual flight, but WestJet and Philippine Airlines have recently applied to Canadian authorities for code-sharing status, opening up the possibility of a Winnipeg-Manila route, Rempel said.

Antiquated airspace

Where we fly

Richardson International Airport’s top 35 markets (destinations without direct flights in bold):

1. Toronto

2. Calgary

3. Vancouver

4. Edmonton

5. Ottawa

6. Montreal

7. Saskatoon

8. Cancun

9. Las Vegas

10. Thompson, Man.

11. Regina

12. Orlando

13. Thunder Bay

14. Halifax

15. London, Ont.

16. Victoria, B.C.

17. Phoenix

18. Puerto Vallarta

19. New York City

20. St. Theresa Point, Man.

21. Manila

22. Kelowna, B.C.

23. Miami/Fort Lauderdale

24. Flin Flon, Man.

25. Chicago

26. Varadero, Cuba

27. Hamilton, Ont.

28. Los Angeles

29. The Pas, Man.

30. Island Lake/Garden Hill, Man.

31. Honolulu/Kahului

32. Abbotsford, B.C.

33. London, U.K.

34. Minneapolis-St. Paul

35. Montego Bay

— source: Winnipeg Airports Authority

The Philippines is one of many countries that don’t have an open-skies agreement with Canada, necessitating a code-sharing agreement. Airport authorities complain Canada is far behind the times when it comes to allowing other airlines not just to land here, but operate within the country, thanks to foreign-ownership requirements that date back to a postwar period when nations owned and operated their own airlines.

The result of antiquated protectionist measures is a lack of airline competition within Canada, at least compared to the airline markets within Europe and the United States, where ultra-low-cost carriers abound.

“You can argue, as many carriers have tried in the past, that our regulatory environment is a barrier to entry,” Rempel said.

“We just don’t have that competition here,” added Duval, saying this explains both the cost of flights in Canada and the availability of flights.

Airline profit margins are notoriously small — as are the returns they offer shareholders. In order for carriers to run profitably in Canada, their planes must operate somewhere in the vicinity of 12 hours a day. In the U.S. and Europe, where population densities are higher, aircraft are expected to operate even more hours daily.

This is why some of the world’s less-profitable destinations have to offer subsidies to airlines, operating under the logic the economic benefits stimulated by direct connections warrant the investment.

Does it ever pay to pay?

Airline subsidies are common in Europe, where ultra-low-cost carriers such as Ryanair sometimes offer suspiciously cheap fares. The practice is less common in North America — but common enough to force municipalities and airports to struggle with the prospect of whether to pay airlines to land.

“There’s a huge danger in it. Just on the philosophy of it, I am often conflicted. I can see what the economic benefit to the community is when a carrier comes in,” said Rempel, estimating the jump in the trade between two cities stimulated by a direct connection at something like 40 per cent.

“If you get too deeply into an incentive program and the company disappears when the incentive is over, all of a sudden you have negative implications beyond just the flight being gone.”

Winnipeg knows this from experience. When a Winnipeg-Denver connection operated by an Air Canada partner disappeared, it took a while to convince United to resume the route. That connection is now profitable, Rempel said.

The reputational risk to a city that offers airline subsidies is too great, added Marina James, president and CEO of Economic Development Winnipeg.

She points to the failure of subsidies in Edmonton as a reason to resist a film-industry call to subsidize a direct Winnipeg-Los Angeles flight.

“We enjoy relatively good access from Winnipeg right now,” she said. “Sometimes, there’s a tipping point where a short-term incentive may be a way to stimulate new pieces. By and large, you would hope the demand would happen naturally.”

Duval, however, said Winnipeg may have no choice but to get into the airline-subsidy game.

Possible help on the horizon

A more sustainable means of boosting flight options out of Winnipeg comes from the hope Ottawa may amend the way it deals with Canada’s major airports, which have chafed against high rents and other charges that drive up the cost of flying.

While most U.S. airports are subsidized by Washington in the form of grants returned from airport taxes, Canadian airports funnel money into Ottawa in the form of $300 million a year worth of rent.

The Winnipeg Airports Authority, for example, expects to pay $6.8 million this year for the right to use the land below Richardson International — a figure nearly equal to the $7.4 million the authority managed to pay down in principal against its $646 million in debt against an asset it controls but doesn’t actually own.

Canadian airline passengers also pay security charges levied by the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority, or CATSA. That money winds up in general revenue and is not returned in full to airports, which must pay for security themselves, said Daniel-Robert Gooch, president of the Ottawa-based Canadian Airports Council.

And Canadian airline passengers must pay Nav Canada fees, GST, PST, airport-improvement fees and — if they’re flying into the U.S. — American taxes and fees.

This pile of extra fees, along with the reduced airline competition within Canada and absence of low-cost carriers, is what leads flights between U.S. cities to be so much cheaper than flights from Canada to the U.S.

As a result of the price differential, Canadians make up about 15 per cent of all airline passengers at Fargo’s Hector International Airport, said Shawn Dobberstein, executive director of the City of Fargo’s Municipal Airports Authority. That works out to about 150,000 passengers in 2013.

Grand Forks International Airport does not keep tabs on its Canadian customers, but Manitoba is part of its catchment area, said executive director Patrick Dame.

Dobberstein acknowledges different funding models in the Canada and the U.S. make up part of the disjunction.

“In the U.S., the government sees airports as more of an economic-development tool and a tourism resource,” he said. “We love the Canadians that are down here, so keep coming.”

Two years ago, the Conference Board of Canada suggested Canadian airline traffic would rise if Ottawa rethought its funding relationship with airports. A federal review of Canadian transportation policy is now underway.

Rempel said he’d like Ottawa to figure out what it wants out of Canada’s airports.

“It’s not just airport rent. It’s our whole transportation philosophy,” he said. “What do we want to be a prime focus of our aviation strategy? Is our prime focus to have a flag-carrier? Is our prime focus the customer? Is our prime focus job creation? What is our main mandate?”

Meanwhile, back at YWG

As for Winnipeg’s passenger volume, Rempel figures the Richardson numbers will go up. He said he’s seen passenger numbers plateau before and then sharply rise.

A new ultra-low-cost carrier in Canada would have the same beneficial effect on Winnipeg as Greyhound Air did in the 1990s and WestJet did the following decade, he said.

“We’re in that cycle where it appears the market is ripe for something like that to happen,” he said.

Even if those passengers don’t materialize this year, Duval said he believes the WAA still made the right move with its $700-million expansion gamble, debt load notwithstanding.

“It’s our gateway to the world,” he said. “It’s not opulent. It’s not an over-the-top, grandiose building. It’s a very functional, stylish building that a market the size of Winnipeg should have and deserves to have.”

bartley.kives@freepress.mb.ca