Carving out a niche in traditional art

Flint-knapping an ancient skill

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/05/2013 (4609 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

PLUM COULEE — “Why are you white people teaching us to flint-knap?” an aboriginal youth at the back of the class asked archeologist Chris Whaley, who was in Cross Lake First Nation teaching that very thing.

Flint-knapping is the making of tools and weaponry, like arrowheads and spear points, out of stone.

“Guess what? My ancestors are from Europe (Ireland),” said Whaley, recreating the conversation. “And guess what? Every country on Earth has had a Stone Age. It’s universal, the making of projectile points, also knives, drills, hide-scrapping tools, etc.”

Whaley’s primary interest in flint-knapping, a surprising hobby with devotees in North America and Europe, is as an archeologist. “To do experimental archeology, you’re trying to do what the early peoples did, to replicate how bone tools were made, how ceramic pots were manufactured. My interest is in stone-tool technology,” he said.

“By reproducing early tools made of stone, we get a better understanding of the challenges those people had, how easy and how difficult it was for them.”

Some extreme hobbyists in the United States even make their own projectile points, like arrows and spears, to use hunting wildlife.

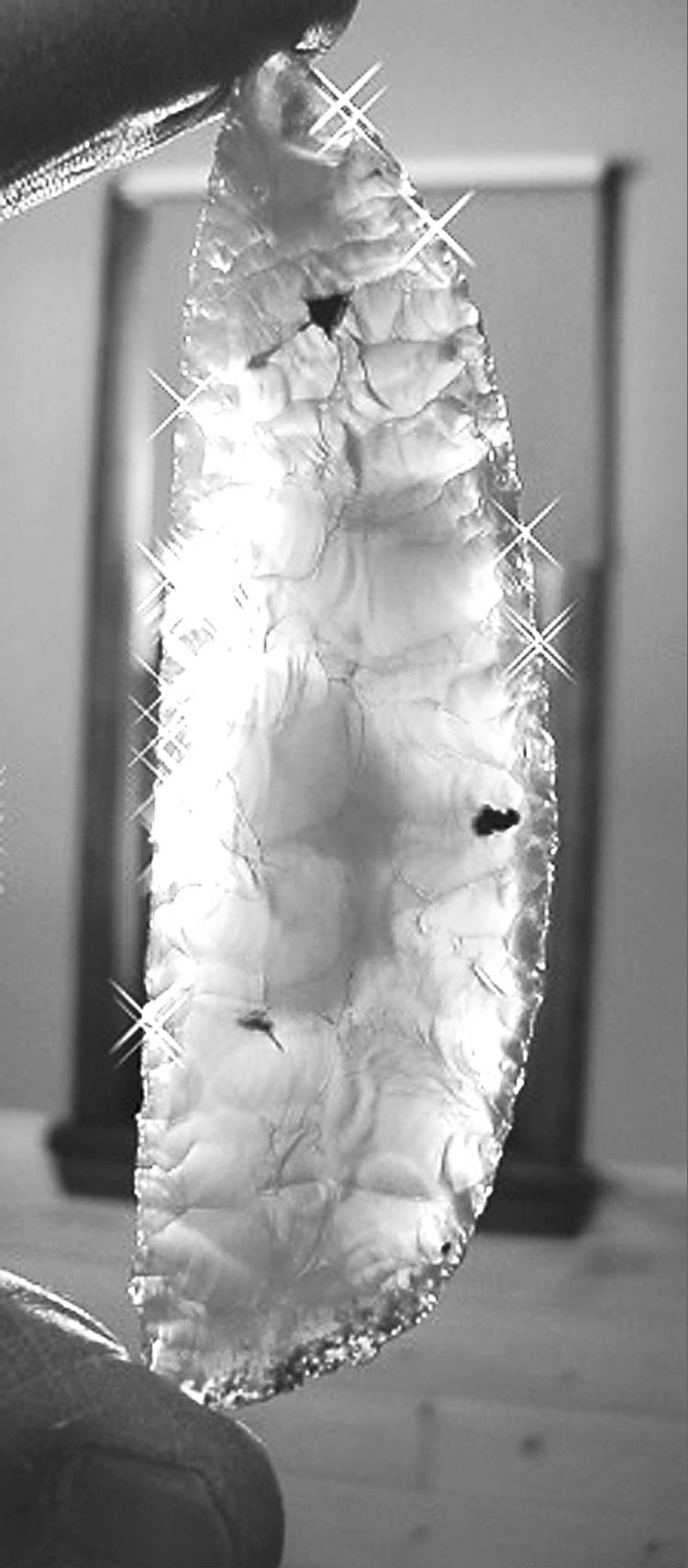

For others, like Neil Fehr in Plum Coulee, who learned the craft from Whaley, flint-knapping is an artistic expression. Fehr makes knife blades from obsidian — black volcanic glass used by early peoples for similar purposes — and then hafts the blades with handles made from antlers.

In fact, Fehr makes a living off his antler-knife handles, sold largely to other artisans of flint-knapping. He sells a box every week, with prices averaging $40 to $200 per handle. “It’s unique for someone to make a living from art in this area (Pembina Valley),” he said.

His knife handles sell to people in places as far off as the U.S., Australia, Germany, Austria and Italy. Collectors and traditional bow hunters buy Fehr’s blades, which he sells on eBay.

“A lot of people in Europe are into the Old West and fur trade,” he said.

Fehr uses obsidian because that’s what First Nations people used to make knives and arrowheads. Obsidian is the sharpest edge known to man and up to five times sharper than steel. Some scalpels made with obsidian are used in microscopic surgery of the eye and brain.

The downside is obsidian is brittle. You don’t want to drop it.

All First Nations people used stone that had a high content of silica — which will chip rather than crack — such as obsidian (almost pure silica) chert, agate and famous Knife River flint. In early times, obsidian was sourced from places like Washington state, Yellowstone National Park and the Rockies.

For antler hafts, Fehr and a friend go shed-hunting every year. Deer lose their antlers every winter and there are central drop-off points where they do so. Fehr has found up to 200 antlers in one area.

He carves images of wildlife or aboriginal motifs, like an eagle feather, into the antler handles. Antler is easier to carve than wood because there’s no grain.

Half-finished cups of coffee are left abandoned throughout his workshop.

Fehr saves them.

“It makes a beautiful stain (with some added ingredients). People often ask where I get my stain. I can’t tell them it’s coffee, so I say I make it,” he said.

Staining gets in the creases and brings out the carved images. Then he heats it with a blowtorch to make the stain permanent. He sands it with steel wool, then oils it with bear fat.

“Bear fat gives it an incredibly shiny finish, but with no sticky residue,” Fehr explains.

His antler handles can be viewed at flintknappers.com.

Fehr’s workshop in Plum Coulee, Loon Magic, which includes many other naturalist art works, is open to the public, starting in June, by appointment.

The term flint-knapping dates back to when people in Brandon, England, mined flints for use in British flintlock muskets, said Whaley, who works for archeological consultant Bison Historical Services Ltd. Knapp comes from the German word “knopp,” meaning to strike or shape.

Whaley estimated there may be half a dozen active flint-knappers in Manitoba. He has given workshops at the Festival du Voyageur and the Mineral Society of Manitoba. He will be giving demonstrations at Aboriginal Day in Brandon on June 21.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca