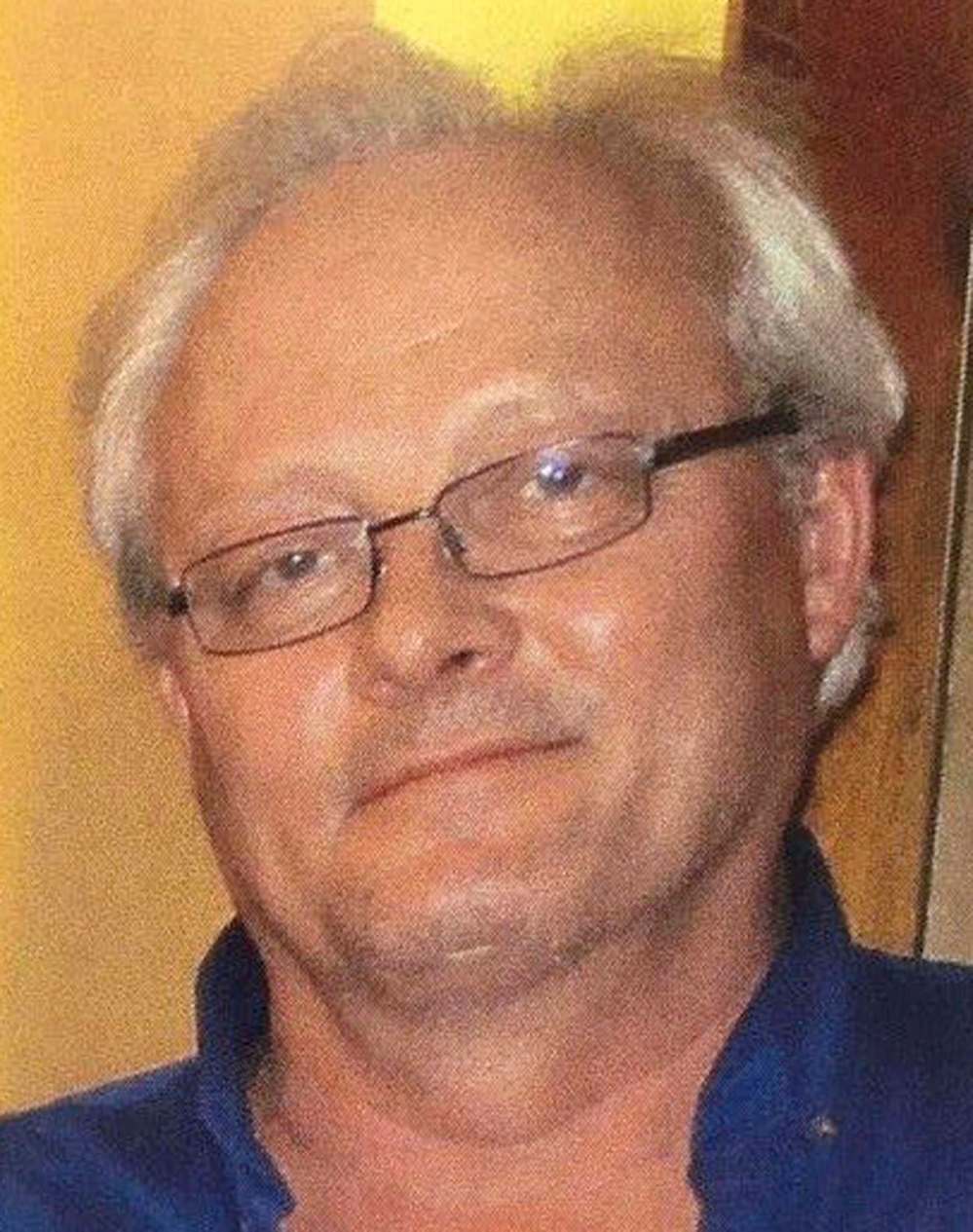

Discrimination ‘altered his life’

City man expelled from military for being gay died before apology to LGBTTQ* Canadians

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/11/2017 (3028 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Darryl Kippen wore his military uniform to the 1978 Winnipeg air show. His parents were proud of their son, who dreamed of a future serving Canada through missions abroad. A year later, the military expelled him for being gay.

“It altered his life; it was something morally destructive for him,” Kippen’s brother, Mike, recalled. “It was hard on him, because he thought he had a future there.”

On Tuesday, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized to LGBTQ* Canadians who suffered persecution through military and public-service purges, discriminatory convictions and police raids.

“These aren’t distant practices of governments long forgotten. This happened systematically, in Canada, with a timeline more recent than any of us would like to admit,” Trudeau told the House of Commons.

“It is our collective shame that this apology took so long. Many who suffered are no longer alive to hear these words, and for that, we are truly sorry.”

Among those is Kippen, who died in August 2016. The 58-year-old had struggled to carve out a new life, with mixed success.

At 18, Kippen enlisted in the Canadian Forces, going for training at CFB Cornwallis in Nova Scotia. He knew he was gay, but the military never said it would be an issue.

In an interview, Kippen recalled the harsh words of his sergeant:

“He told us during class that the armed forces is no place for queers, and that if anyone was approached by a queer they should get a bunch of the guys, take him into the barracks and beat the shit out of him,” Kippen said in a March 1983 interview with The Body Politic magazine.

Kippen avoided any romantic relations. But the military figured out he was gay three years into training, after an official followed his movements around the base. They pushed him out under “sexual deviation.”

Mike recalled his brother’s excuse: “He told us he quit because there were too many gays in the military.”

At 21, Kippen married a woman, but separated months later. He came out to his family, and took a job with Big Brothers, mentoring children. The organization later fired him when officials found out he was gay.

In July 1987, he told the Manitoba legislature about being sacked for his homosexuality. “I did not catch it, I was not recruited, and homosexuality is not transmittable,” he said during hearings when the government amended its human rights code.

“I hold in disdain those legislators who have compared my life to people who engage in bestiality, necrophilia and pedophilia,” he said.

On Tuesday, Trudeau referenced the “witch hunt” fuelled by those ideas. “Their names appeared in newspapers in order to humiliate them, and their families.”

The prime minister spoke at length about police entrapment and unjust laws. He mentioned the so-called Fruit Machine, which had public servants and RCMP employees watch pornography while having their pupils, perspiration, and pulse measured, to test for an erotic response.

“We cannot forget our past. The state orchestrated a culture of stigma and fear,” he said.

Trudeau promised $145 million, mostly to settle a class-action lawsuit and compensate people who were purged from the military, RCMP and public service. Of that funding, $15 million will be used for a national monument, museum exhibits, archives and educational campaigns. There will also be a toll-free support number (1-800-487-7797).

The Liberals also tabled a bill that would expunge criminal convictions for consensual sexual acts. They earmarked $4 million so bureaucrats can screen an estimated 6,000 sentences for buggery, anal intercourse and gross indecency. People who were convicted, or their next of kin, would have to apply, free of charge.

Other party leaders spoke about the lost potential of Canadian soldiers, the hard work of activists and Canada’s criminal laws on HIV exposure, which remain among the toughest in the world.

A few Conservatives did not stand or applaud, including Provencher MP Ted Falk.

Jim Kane paid to fly to Ottawa from Winnipeg to take in the apology. He was among the 250 people who marched in Winnipeg’s first Pride parade in 1987.

“It was more thorough than I’d anticipated,” he said, amid a celebratory toast. “It showed that we’ve come a long way.”

Kane recalled a friend — who turns 80 soon — who served six months at the Headingley jail for holding hands with a man near the Manitoba legislature grounds.

“I’m just glad that this was done before he passed on,” he said, breaking into tears. “We fought so long and hard.”

Among those was Kippen, who refused to stay in the closet.

He spent the rest of his career working at a halfway house and eventually running a Transcona employment centre, where he supervised Kevin Walsh. The two became close friends, talking at length about politics.

When his parents died, Kippen used his inheritance to help bring two LGBTQ* Iranian refugees to Winnipeg, travelling to Turkey to meet them.

“That’s who he was,” said Walsh. “He was always about helping people.”

In his spare time, Kippen painted and drove the cars he collected. But he was increasingly reliant on alcohol, and his brother, Mike, said a few drinks would send Kippen into a spiral.

“He just got very vocal about stuff in the military. He couldn’t let it all go. You could tell it was something that really stuck with him, all his living days, really. It held him back.”

Walsh recalls similar incidents. “Those last few years just ate away at him. He was so angry. Underneath, there was an untrusting of everyone.”

Kippen died in August 2016, after falling down a flight of stairs; a coroner ruled it accidental and not related to alcohol. Friends also then learned he had no money.

“He’d phone and ask if I wanted to help with some of his business projects. And we found out later this was money he needed to survive.”

Mark recalled the last time he saw his brother, when they camped at a lake over the Canada Day 2016 weekend. He’d mentioned repeatedly that an apology would be coming.

Walsh said the apology almost became an obsession in his last months of life.

“It just really destroyed him inside. This day was going to mean so much to him.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Wednesday, November 29, 2017 10:00 AM CST: corrects name