Hard time and fresh air at former jail

Winnipeg General Strike leaders among inmates-turned-farmers

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/07/2012 (4833 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

NEAR EAST BRAINTREE — It wasn’t exactly the Great Escape.

Two prisoners doing time for theft at the former Manitoba provincial jail, near East Braintree, had slipped out in the middle of the night, the Free Press reported on Oct. 16, 1925.

There were no roads, and certainly no nearby Trans-Canada Highway, back then. There was only a horse trail leading to the prison, and a railway track. And an unattended railway jigger, or hand-operated rail car.

The prison certainly had more famous inmates — that honour goes to leaders of Winnipeg’s 1919 General Strike. But you can’t beat the image of two convicts, outfitted in the latest line of prison smocks, pumping madly down the tracks to freedom, like something out of a Buster Keaton movie.

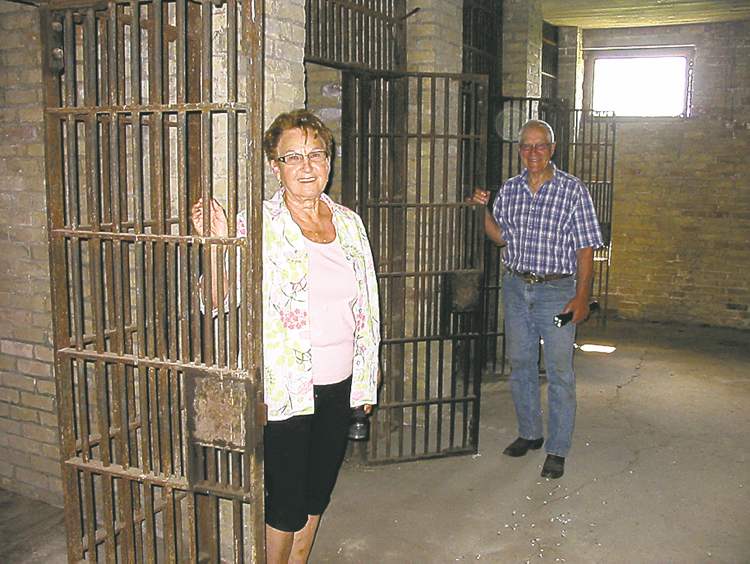

The fates of Tony Totill, 33, and Richard Lawrence, 17, aren’t known, but the remnants of the old prison — it operated from 1918 until 1930, when prisoners were transferred to its replacement, the new Headingley Correctional Institute — still stand on Carl and Lorna Feilberg’s farm, about 100 kilometres east of Winnipeg.

“This was heaven for the prisoners,” said Carl, 80, whose father purchased the property several years after the prison closed. “There were deer and bear and moose all around.”

It was still considered experimental to have prisoners work outdoors instead of rot in jail cells. In theory, nurturing nature on a prison farm was supposed to nurture prisoners out of recidivism.

(The Harper government killed federal prison farms in 2010, including the program at Manitoba’s Rockwood Institute.)

The official name was Manitoba Industrial Farm but the Free Press also called it the Birch River Prison Farm. Its main enterprise was having prisoners clear the land and farm. But a quarry was also discovered on the other side of the Birch River on the edge of Sandilands Provincial Forest.

The prisoners cleared 300 acres of forest and, in those days, did it with grub hoes — a kind of sideways axe for cutting roots so horses could pull down the trees. The prisoners built their barracks, bunkhouses for the guards, and other wood buildings. With rock from the quarry, they built a stone barn, a four-cell detention block for prisoners who broke the rules, and the shell of a two-storey home for the prison superintendent that wasn’t completed.

Escapes were rare because there was nowhere to go unless you got your hands on a railway jigger. There was a team of bloodhounds in case someone escaped, which were said to be useless.

Strike leaders like William Ivens were among the prisoners. Ivens, who became head gardener, was imprisoned for writing daily strike bulletins in the 1919 General Strike. Manitoba justice officials called it “seditious conspiracy.” The public thought otherwise, electing Ivens to the Manitoba Legislature in 1920 while incarcerated, surrounded by bush and unable to campaign. He was elected as member of the Dominion Labour Party.

John Queen was another noted strike leader imprisoned here. In 1935, he was elected Winnipeg mayor, serving until 1942. A local history book here says Queen was known to give impromptu “stump” speeches — literally. He would throw down his axe, stand on a freshly cut stump, and extol the virtues of socialism to fellow inmates.

The prison could accommodate up to 75 inmates but usually topped out at about 55. Prisoners earned up to 25 cents a day. “There was no one dangerous kept here,” said Carl.

All of its stone buildings are still standing. In 1977, Carl and Lorna converted the shell of the two-storey granite house — it had an elm tree as high as the roof line growing out of the floor — into a gorgeous home for themselves. Its walls are 26 inches thick.

But the prison’s grain crops were a failure. The forest soil was simply too thin. The prison was too far away from Winnipeg, prompting construction of Headingley, which also began as a prison farm.

The Feilbergs have used the land mainly for growing hay and keeping cattle, as well as running a logging business.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca