Inadequate equipment, insufficient safeguards

Ombudsman backs concerns by whistleblower who sounded alarm over breathing machines at Brandon hospital

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/04/2018 (2811 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

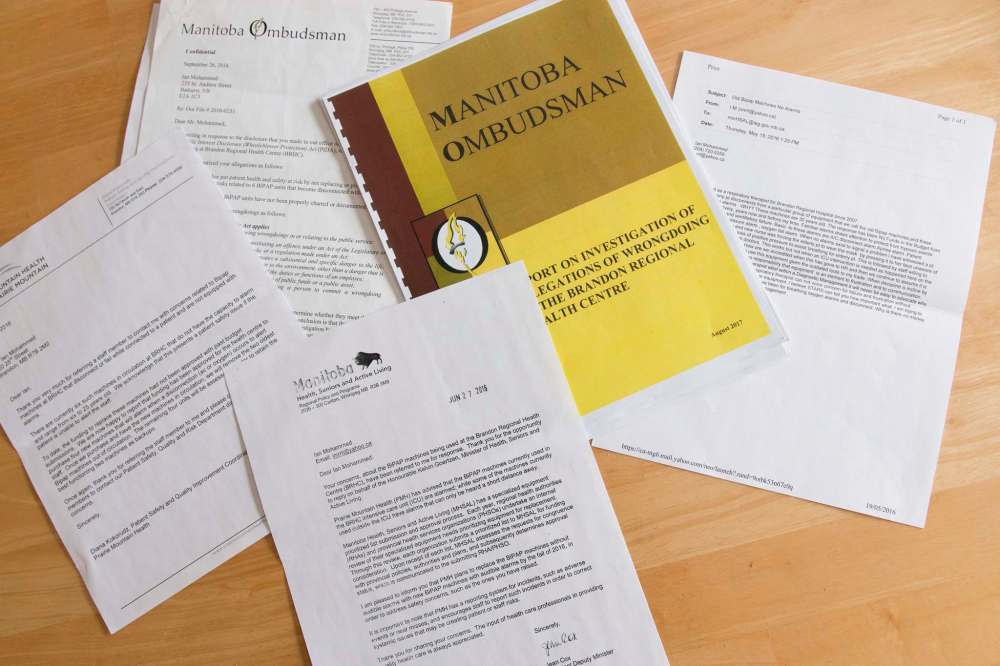

For at least 20 months, the Brandon Regional Health Centre knew it was using vital breathing support machines not equipped with any alarms to signal a potentially life-threatening disconnection, and it failed to properly mitigate the risk. That’s among the findings of a confidential ombudsman report shared with the Free Press by the whistleblower who sounded the alarm.

Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP) machines are crucial for patients who don’t get enough oxygen when they inhale. They’re known to occasionally disconnect, sometimes from the pressure of high oxygen flow and other times if they become tangled when a patient rolls around in bed.

A third-party expert cited by the ombudsman’s office makes the risks clear: “For patients who were less oxygen dependent, this could lead to patient discomfort and shortness of breath. For patients who were very oxygen dependent, this could lead to hypoxia, respiratory distress, and eventually cardiac arrest.”

Newer models are equipped with an alarm to notify staff in the event this happens, but until last year, the Brandon hospital relied on six machines it acknowledged “did not have the capacity to alarm.”

The hospital’s safety measure, implemented after a patient died from a similar disconnection on another breathing machine in the summer of 2015, was “red taping.” That involves sticking red tape on the oxygen line so it’s clear to all staff in the room if it disconnects. It was believed nurses could easily check it when they did their rounds every 30 minutes.

The ombudsman’s investigators concluded that measure wasn’t good enough, in part because respiratory staff told them it wasn’t an adequate safeguard. After all, for some patients, the impact would be visible within minutes.

“Increased patient supervision was an option available during that time which was not exercised,” the report says.

It was never exercised. Not months later, after a fall 2015 incident, when tubing for a BiPAP machine dislodged while a patient was rolling around in bed. The patient wasn’t injured, but the staff member who wrote up the incident recommended an external alarm in case it happened again.

It wasn’t exercised after a February 2016 incident that left respiratory therapist Ian Mohammed with post-traumatic stress.

Mohammed, who worked for nearly a decade at the hospital, spurred the ombudsman’s investigation. And while he considered asking the Manitoba Labour Board to rule on whether he’d faced reprisals from the hospital as a result of speaking up, ultimately he just wants Manitobans to be made aware.

“You come to the hospital with a lot of trust,” Mohammed said. “Most people understand therapy could go wrong but they reasonably expect that we will be truthful… that we will tell the risks that come with things.”

Only one respiratory therapist worked the night shift at the hospital. That’s still the case now, even following a staffing review recommended by the ombudsman. “We don’t have the amount of work required for them,” said Brian Schoonbaert, chief operating officer at the Brandon Regional Health Centre.

But that’s not what the therapists interviewed during the ombudsman’s investigation said. According to them, it’s a busy shift: they cover the whole hospital on their own, often foregoing charting to answer pages or field urgent calls for help. That’s how it was, Mohammed said, on the February night when he was the lone therapist at work and a patient’s BiPAP machine disconnected.

Mohammed started his shift in the emergency room around 8 p.m. He said he knew he needed to see a patient later to test her oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, but he couldn’t get away from the ER until 9 p.m. When he walked in the room, his first thought was, “why didn’t they call me for an emergency?”

The woman was lying on her hospital bed. A nurse had a mask pressed to her face but Mohammed could tell she wasn’t getting the oxygen she needed. The equipment next to her was tangled, as if she’d been struggling. Two years later, he still remembers her eyes.

“It was something I could feel,” Mohammed said, “really desperate.”

He scanned the equipment line, leaning in close until he could hear the telltale hiss of the disconnect. Mohammed reconnected the line and the oxygen flowed. The next day, shaken, he asked for a meeting with his supervisor. He told her he didn’t want to put the machine on someone again, that he wouldn’t.

Mohammed told the Free Press he specifically asked for the right to refuse work he believed to be unsafe. He alleges his supervisor refused.

In a statement released in response to questions about the allegations, Schoonbaert said “staff always have the right under Workplace Safety and Health legislation to refuse dangerous work and if there was a concern, the employee could raise it under that premise.”

Mohammed kept working. He said he did his best to avoid having to use the BiPAP machine and continued to push for meetings with his superiors.

After one tense meeting in May 2016, Mohammed broke down and wrote to the hospital’s patient safety and quality improvement co-ordinator.

“I told her that I almost killed someone,” he said. “I get the feeling that I might be asked to do it again.”

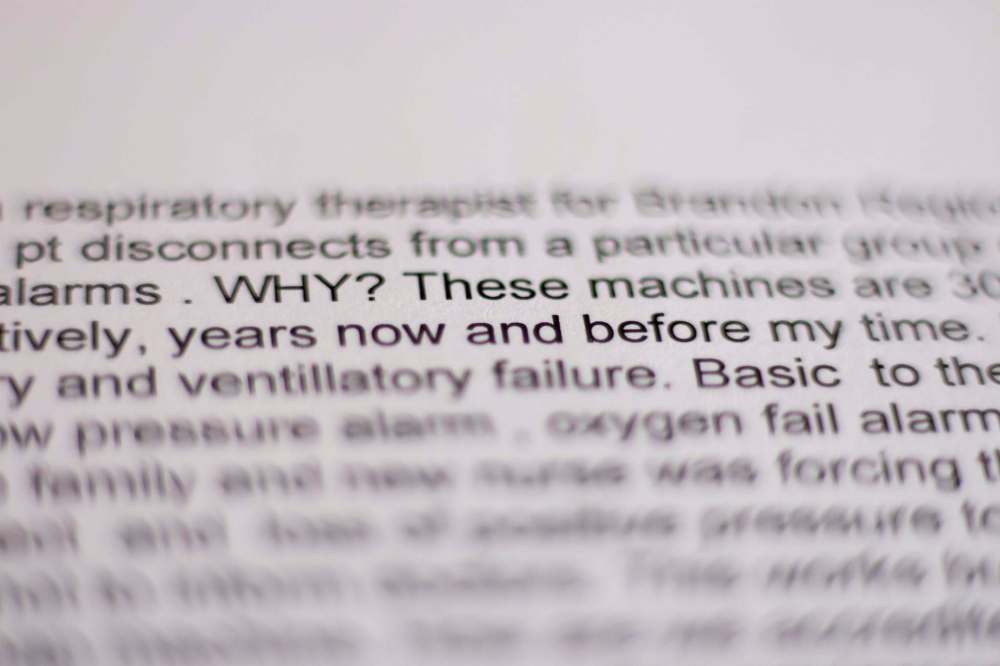

He wrote a letter to Health Minister Kelvin Goertzen. He told the minister that he had watched a patient suffocating, watched a novice nurse holding the mask to the woman’s face without realizing the machine had disconnected. “Why is there no money?” Mohammed asked. “How are these machines acceptable to any management?”

The hospital started requesting funding to replace its BiPAP machines, which ranged in age from six to 25 years old, in 2013-14. In total, it asked for funding for four consecutive years. Because BiPAPs are considered basic equipment, funding requests are considered at the regional level, not the provincial level. Asked about safeguards in cases such as this, a spokeswoman for Manitoba Health said the region is “responsible for clinical services delivery and planning, as well as determining the priority of within region risks, risk planning and mitigation.”

In February 2016, funding to replace the machines came through although there were further delays, according to the ombudsman’s report, when the funding was “identified to be insufficient to cover the cost of the desired safety features.” (The approximate cost for a basic machine is $4,000.)

That meant new machines weren’t in circulation until February 2017. Mohammed said he thought that was an unconscionable delay given the circumstances. Schoonbaert said it’s not just about respiratory therapy, but “a matter of trying to balance all the needs within the entire region.”

Mohammed spent most of 2016 on mental health leave, going home to New Brunswick to deal with post-traumatic stress.

He tried once to return to work in August, but there were no new machines yet and hospital staffing protocol remained the same.

“There was no change,” Mohammed said, “I had the same concerns.”

It was during that trip back to Brandon that Mohammed wrote down his concerns and filed them, formally, with the ombudsman’s office.

Mohammed said the investigation was a relief and he felt vindicated. The investigation also revealed a disconnect between the hospital’s respiratory therapists and management.

“We have had no problems with machines to a large extent,” said Schoonbaert, who wanted it made clear that the patient who died in 2015 was using a Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) machine, not a BiPAP.

“Any of the staff who knew of this incident were very much aware that it was a patient’s private CPAP machine from their home,” he said. “It was a very unfortunate event but it was a very different scenario.”

However, the ombudsman report says that many respiratory therapists seemed to be under the impression that the person died while using one of the six BiPAP machines.

“(Respiratory therapists) believed that a patient died using an unalarmed BiPAP unit, and this event did not lead to either the units being replaced or any enhanced patient supervision,” the report says. Regardless, the report says, the circumstances of the patient’s death should have been enough to alert the hospital to the risk of using unalarmed machines, BiPAP or otherwise.

In that case, the patient’s CPAP machine became disconnected, cutting off the oxygen source. There was no alarm and by the time the patient was found, he or she was “unresponsive, without breathing or a pulse.” The person died a short time later. The hospital’s response was to make sure all machines were on the same side of the beds as the oxygen source to minimize the risk of entanglement and introduce “red taping.” The response did not include increased supervision.

The next documented incidents were tubing dislodgement in 2015 and Mohammed’s patient in February 2016, although the ombudsman says there’s a dearth of charting about disconnections, making it impossible to evaluate the frequency with which they occurred.

The report says respiratory therapists considered the disconnections to be “a weak point” within their unit — one that irregular, non-mandatory staff meetings failed to address. Each therapist interviewed had either experienced a disconnection with one of their patients or had heard about a colleague’s disconnection. One person said they happened at least once a year, while several more said they happened “every few months or even more frequently.” Had incident reports been filed, the ombudsman says, problems with the machines might have been properly addressed and there might not have been a “sustained” risk to patients.

The new BiPAP machines were installed in February 2017 and Mohammed was supposed to start on a gradual return to work in April. It lasted less than one morning, he said.

He had heard from former colleagues about an incident in which one of the new machines disconnected without sounding an alarm because a staff member hadn’t been properly trained on how to operate it. He wanted to ask about that, Mohammed said, but instead the conversation became heated, and ended. He alleges he was fired and escorted out of the building by security. The health authority disputes that.

“We can confirm that no one was fired,” Schoonbaert said, but “specifics of personnel issues will not be discussed publicly.”

He went on to say the health authority considers “the case closed.” Mohammed, knowing there is still only one respiratory therapist making the rounds at night, does not.

jane.gerster@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @Jane_Gerster

History

Updated on Saturday, April 14, 2018 7:28 AM CDT: Final