Poking holes in privacy

Hospitals, health authorities deal with inappropriate access to patient files on a case-by-case basis, but nobody's keeping track overall

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/01/2019 (2611 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

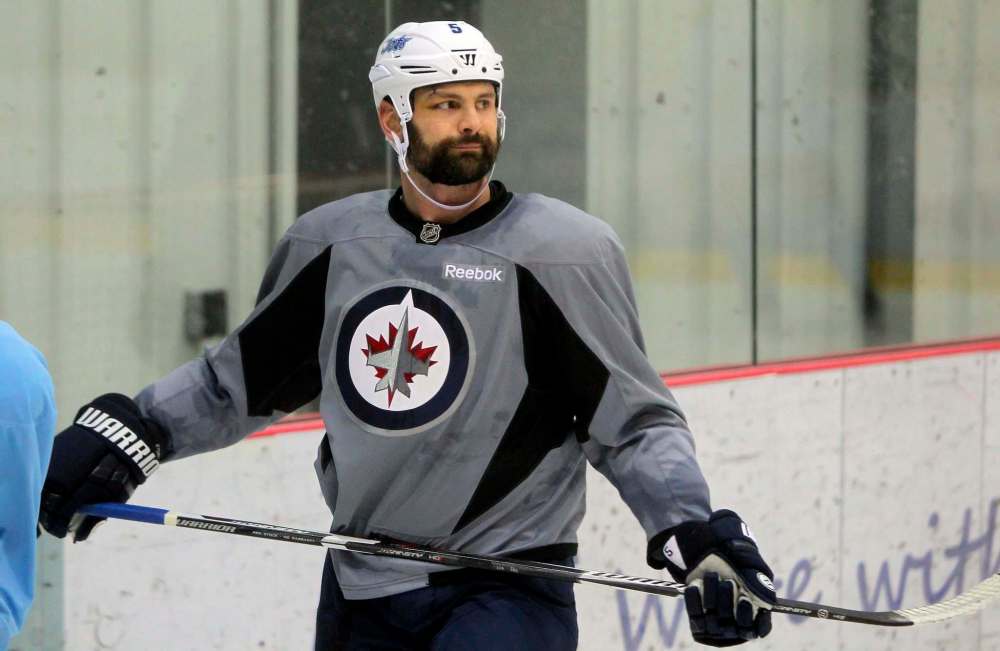

In May 2015, a Grace Hospital employee was fired for snooping into the personal health information of five Winnipeg Jets players.

The matter was dealt with quietly. The Jets — just one of whom is still on the club’s roster — were notified by letter that their electronic health files had been inappropriately accessed. The matter was not made public.

Winnipeg hospital officials had been alerted by a whistleblower some months earlier about chronic snooping by the Grace employee, an avid hockey fan who was curious about the severity of injuries suffered by Jets players, a source told the Free Press.

Human error

The Winnipeg Regional Health Authority says it conducts “regular compliance audits” of its electronic patient information systems to detect breaches of privacy.

While it provided no statistics on how often privacy breaches occur, the health authority said they are generally a result of “human error,” as opposed to actual snooping.

The Winnipeg Regional Health Authority says it conducts “regular compliance audits” of its electronic patient information systems to detect breaches of privacy.

While it provided no statistics on how often privacy breaches occur, the health authority said they are generally a result of “human error,” as opposed to actual snooping.

Most instances of snooping involve staff looking up information on family members or co-workers, the health authority says.

“It’s important to recognize that we give employees access to electronic (health information) systems based on their role and function. People who have no need to access a system with patient information in it don’t have access to it,” says Lori Lamont, the WRHA’s acting chief operating officer.

She says some employees have only limited access to patient information.

All employees within the WRHA must undergo training about their obligations under the province’s privacy laws. The health authority says it is policy that all employees report any known or suspected breach to their supervisor or privacy officer. Each hospital has privacy officers that serve as the point person for compliance under the Personal Health Information Act.

The WRHA says it conducts both routine and targeted compliance audits in known cases where high-profile individual receives care. Lamont said there was extra scrutiny on the electronic records system, for instance, when former U.S. president Jimmy Carter was treated in a Winnipeg hospital for dehydration in July 2017 while working on a local Habitat for Humanity construction site.

Electronic systems containing personal health information must be able to produce a record of user activity, and that record is required to be maintained for at least three years. The WRHA says it has retained this information in its systems since their creation.

“It is possible for us to review previous activity depending on the age of the system,” WRHA spokesman Paul Turenne told the Free Press in an email. “When potential PHIA breaches are reported to us, we take these seriously and initiate an appropriate investigation.”

In recent years, the WRHA has taken steps to raise awareness of the requirements of PHIA, working with professional colleges and unions to reinforce employees’ obligations under the act. Employees are required to undergo online PHIA training every three years, Turenne says.

Messages reminding staff of their obligations to maintain patient privacy are ubiquitous throughout the health system, the WRHA says. These include screen savers that stress the importance of the appropriate use of technology and the fact that employee activity is audited.

NHL hockey teams generally reveal little information when players get hurt, vaguely describing them either as “lower body” or “upper body” injuries. Far more detailed information is just a few keystrokes away for someone with access to the city’s electronic patient records system. For the former Grace employee, the temptation was just too much.

“This was an overzealous Jet fan, (a) really impassioned fan, and he wanted to know… ‘how long is this player going to be out?’ So that’s why he’d do that,” said the source, who is not being identified by the Free Press because of concerns about repercussions

The Jets fan paid a heavy price for his repeated snooping and has yet to find a job in his field since being canned. However, other employees in the roughly five dozen-member department at the Grace — as many as half of that group — were also snooping on patient records at the time, and they continued to work at the hospital, the source said.

“Staff talked about it (snooping) openly,” the source said, adding they were “much more careful” after their colleague was fired.

The targets of this illegal prying included friends and family members of staff members, colleagues and Winnipeg Blue Bombers players (none of whom is still with the club). Hospital authorities were made aware of the allegations, although there is no evidence anyone else was punished, the source said.

At about the same time hospital officials learned about the Jets breach, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority went public about a Grace pharmacist — a different employee in a different area of the hospital — who had snooped into the health records of “at least 56” patients. He was also dismissed.

Why would the WRHA disclose one incident and not the other? The reasons are varied and complex.

In the case of the pharmacist, the sheer number of accessed files forced the health authority to go public in an attempt to ensure all victims were told about the breach. In the case of the handful of high-profile Jets, they could be quietly notified.

The Free Press attempted to contact each of the targeted Jets, either through their agents or team intermediaries. Only one, former defenceman Mark Stuart, responded, confirming through a club spokesman he had received a letter from local health authorities informing him his personal hospital information had been inappropriately accessed.

•••

How often do health-care workers inappropriately access electronic health files? How many hospital employees have been fired for snooping? Is the problem getting better or worse? We don’t know. The WRHA is extremely tight-lipped on the issue, citing privacy legislation.

The health authority does not keep statistics on how often employees are caught, although individual hospitals may collect that information, acting chief operating officer Lori Lamont says.

“I become aware of some of them (instances) in my role of chief nursing officer,” she says.

Lamont won’t say how many Winnipeg hospital staffers have been fired for snooping, explaining that would contravene the region’s human resources policies.

“It’s not information we share,” she says, discounting the suggestion providing statistics is different than commenting on individual situations.

Neither will she say how many health staffers have been disciplined during the last five years for breaching the province’s Personal Health Information Act.

“We don’t have stats (on discipline cases) unless it resulted in termination,” she says. “Any other discipline isn’t recorded in the (region’s) electronic system, it’s recorded in the employee’s file.”

“If there is a privacy breach in a particular area, there may be particular attention to staff in that area or staff in that department across the system.”

Asked directly to confirm whether a hospital staff member was fired for accessing the files of several Winnipeg Jets players, Lamont says: “I can confirm that we have disciplined, including dismissal… people who have snooped on particular high-profile individuals.”

Were they Winnipeg Jets?

A WRHA communications staffer cuts in, saying answering the question could identify the affected individuals or staff involved.

Lamont says any patients whose records were discovered to be inappropriately accessed are informed about the privacy breach.

“If it was a large group of people… we would go out publicly to ensure that people are aware,” she says.

“Where it is a small group of people who would be easily identified — unless there is a reason that that individual or small group of individuals want us to be speaking about it publicly, we would not.”

A statement issued by the WRHA says several factors, including an employee’s work record, are considered when determining appropriate disciple in such cases.

•••

The whistleblower in the breach of Jets information is no longer employed by Grace Hospital or the WRHA; the employee says he became the subject of bullying and harassment within the department after his co-worker was fired.

While the worker didn’t volunteer having been the one to tell officials about their colleague, others in the department had no doubt based on that individual’s clear opposition to the behaviour.

The whistleblower was initially offered employment in another part of the hospital but feared administrators could not offer protection from continued harassment. A job at another hospital was offered, but it involved a pay cut and other undesirable conditions. The former employee’s union has filed three grievances that have yet to be resolved.

Health privacy breaches in the news:

2011: The provincial ombudsman investigates a privacy breach at CancerCare Manitoba. The probe results in a recommendation that snooping on patient files be made explicitly illegal.

December 2013: The law is changed, making it an offence to access patient files without authorization. The maximum fine is set at $50,000.

2011: The provincial ombudsman investigates a privacy breach at CancerCare Manitoba. The probe results in a recommendation that snooping on patient files be made explicitly illegal.

December 2013: The law is changed, making it an offence to access patient files without authorization. The maximum fine is set at $50,000.

September 2014: The public is informed that a doctor’s laptop, containing the personal health information of 322 patients, was stolen from a Winnipeg office. The laptop was not password-protected, and the MD violated protocol for storing the information on the device. There is no word on whether the physician was disciplined.

November 2014: Manitoba’s ombudsman investigates a breach of protocol that saw a provincial health employee access the personal health information of at least 13 people. The employee was later fined.

March 2015: The Winnipeg Regional Health Authority informs the public it has parted company with a pharmacist at Grace Hospital after discovering he inappropriately accessed the medical records of 56 patients. Health officials say they discovered the breach during a routine audit of the electronic health records system.

November 2016: The public learns that a file containing the personal health information of about 1,000 patients was stolen from a locked office at Health Sciences Centre.

November 2016: A former longtime Manitoba Health Department worker inappropriately accessed health records to find addresses to send out birthday cards, the public is told. Close to 200 records were inappropriately accessed. The department says the employee has “moved on” from her job.

May 2017: A nurse is fined $1,000 by the College of Registered Nurses for providing a volunteer with unauthorized access to medical records. Four nurses were censured by the college for similar breaches a year earlier.

May 2018: It’s learned that a nurse scrolled through the private records of about 1,600 patients of the Grace Hospital emergency department. The WRHA says the individual accessed the files out of a desire to learn. Health officials were tipped off to the nurse’s actions a couple of months earlier. The nurse no longer works for the WRHA.

Although the hospital made an example of the employee who accessed the Jets information, it does not appear to have pursued disciplinary actions against others in the same unit who are also alleged to have inappropriately accessed patient files, the source said.

The Free Press has viewed copies of emails sent by the whistleblower to Conne Newman, the executive director of human resources at Grace, referring to past efforts to sound the alarm about widespread snooping.

In one email, dated May 1 of this year, the whistleblower wrote, “I tried to provide the (WRHA) privacy office with the information I had. They stopped me from providing names and told me that they’d get back to me…. That never happened. I was never provided with an explanation for why they weren’t interested in the information I had.”

Hospital authorities were interested in getting to the bottom of the Jets breach, the source said. They appeared particularly concerned the employee who snooped might have been selling the information or using it for gambling purposes. They were told the employee was simply trying to satisfy his own curiosity about the players’ injuries.

The Jets received little, if any, treatment at Grace Hospital; most, it appeared, took place at St. Boniface Hospital, which is where the whistleblower first raised the allegations — anonymously by telephone in early 2015 — informing officials snooping was rampant in his department at a community hospital in the city.

The price for doing the right thing in this case was a secure job the individual had held for decades, in addition to the bullying and harassment.

“I’ve lost about $10,000 in the process in lost wages,” the ex-employee said in a May 10 email to Newman. “There’s been a heavy toll on my health.”

The individual has since found other work.

Meanwhile, in a response to a Free Press freedom of information request during the summer, the WRHA reported there were two investigations for employee snooping at Grace in 2015. The health authority provided no additional details. Presumably, the investigations related to the pharmacist who was fired and the inappropriate accessing of Jets medical records.

•••

Hospitals are required by law to record such breaches, but neither they nor the WRHA are obliged to keep statistics on such matters, says Manitoba’s acting ombudsman, Marc Cormier.

Neither are trustees of health information obliged to report privacy breaches to the ombudsman’s office, although Cormier, who is also the province’s acting chief privacy officer, says he would like to see that changed.

“We made recommendations for a change to the legislation to require that serious breaches that have a particular risk to that person — to the individual breached — that those be reported to our office,” he says.

The province is reviewing both the Personal Health Information Act and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

“It’s fully voluntary (to disclose privacy breaches to the ombudsman) and we do encourage all the trustees to report to us when there’s snooping or any other kind of breach,” Cormier says.

“The reason we want that information is that there could very well be an investigation that follows, so we may be getting a ton of complaints about that breach.”

If the ombudsman’s office were informed of privacy breaches, it could provide guidance to trustees and examine how they are fixing the problem, he adds.

Nancy Love, deputy ombudsman responsible for access and privacy, says any “intentional breach” of a patient’s health information is considered a risk to that person and should be reported to the ombudsman. The victim does not need to be a public figure, she says.

“It could be somebody snooping on their neighbour, their former spouse… (or) somebody they just associate with in the community or at work. Those are all serious breaches… that we’d want to know about,” Love says.

Beginning in March, Ontario is requiring custodians of health information to provide annual statistics about privacy breaches.

Cormier says if the law changed to allow that here, it would be relatively easy for his office to track any patterns in privacy breaches and help facilities deal with any shortcomings.

Last year, the ombudsman’s office received 26 written reports of privacy breaches from trustees — which can include hospitals, clinics, personal-care homes, laboratories, doctors, nurses, among others — but not all involved cases of snooping.

Cormier won’t reveal the sources of the breaches while the reporting system is still voluntary, because that might discourage individuals and facilities from reporting.

“Right now, the trustees are telling us stuff out of the goodness of their hearts, I suppose,” he says.

There have been only three criminal prosecutions under the Manitoba Personal Health Information Act since its inception in 1997, and only one case involved snooping.

In one case, an optometrist was charged with selling personal health information to a lens manufacturer. In another, a doctor did not properly dispose of patient records after going out of practice, leaving them unattended in a building.

The lone prosecution for snooping occurred in 2017. A former provincial government employee was fined $7,500 for looking into the health records of his estranged daughter. Public prosecutions are rare, in part, because the victim must agree to have the case proceed to court.

Self-regulated health professions, such as those presiding over pharmacists and doctors, are able to discipline members for breaches. The results of discipline cases are made public under those organizations’ governing legislation.

However, health information trustees would be breaking privacy laws if they identify anyone accused of snooping into patient information or if they divulge what, if any, penalties are assessed.

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Tuesday, January 1, 2019 6:58 PM CST: Updates headline

Updated on Tuesday, January 1, 2019 7:06 PM CST: Fixes tile headline

Updated on Wednesday, January 2, 2019 12:49 AM CST: Removes thumbnail photo

Updated on Wednesday, January 2, 2019 8:34 AM CST: Replaces photo