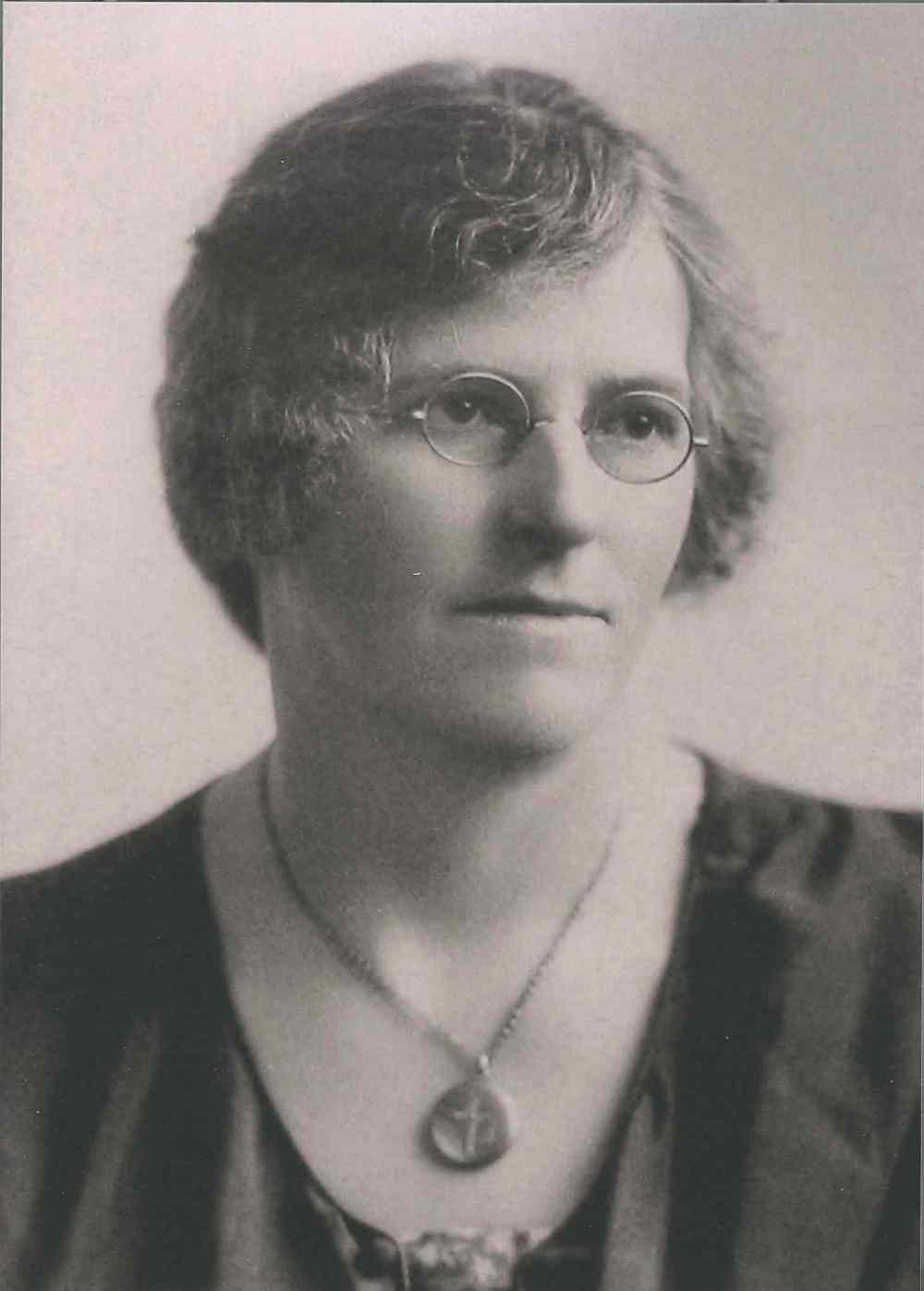

Political pioneer

Jessie Kirk was Winnipeg's first female city councillor

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/10/2014 (4154 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Women have been able to vote in Manitoba municipal elections since the mid-1890s, provided they owned property.

It wasn’t until 1916 that the rules were changed to allow women to seek civic office. The first woman to run for Winnipeg city council was Alice Holling in Elmwood in 1917, but Jessie Kirk became the first woman to win a seat in 1920.

Kirk was born in Chesterfield, England in 1877, one of 11 children. She trained as a teacher, eventually becoming principal of a school in Derbyshire. After the First World War, she came to Winnipeg with her husband, William, and daughter, Mary, and settled on Jessie Avenue. Kirk resumed her teaching career, first in Lockport, then in Winnipeg at Isaac Brock, Principal Sparling, Mulvey, Greenway and Brooklands schools.

During this time, Kirk became a prominent member of the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council. She sometimes appeared before city council and spoke at other public meetings about issues such as the need for a living minimum wage for female civic employees, better unemployment-relief schemes and for women to be citizen appointees on civic bodies such as the police commission and parks board. A matter of particular interest to Kirk was the dismal state of Winnipeg’s housing stock. She openly called on “war profiteers” to donate some of their spoils to support new housing programs.

In April 1918, Kirk was informed her teaching contract would not be renewed. A delegation from the Trades and Labour Council appeared before the school board to publicly accuse them of firing her for being so outspoken. The board denied this, saying many contract teachers had been let go. Kirk’s contract was eventually reinstated, and she was teaching at Brooklands School in September.

In April 1920, Kirk won the nomination of the Dominion Labour Party to run for a seat in the Manitoba legislature. Two weeks later, however, the party’s executive annulled all nominations in order to put the names of the Winnipeg General Strike leaders, being held at the Stony Mountain prison on sedition charges, on the ballot. Kirk said, “As much as I would like to see a labour woman in the provincial house, if labour’s cause would be better served by running the men incarcerated, I am perfectly willing to withdraw as a candidate.”

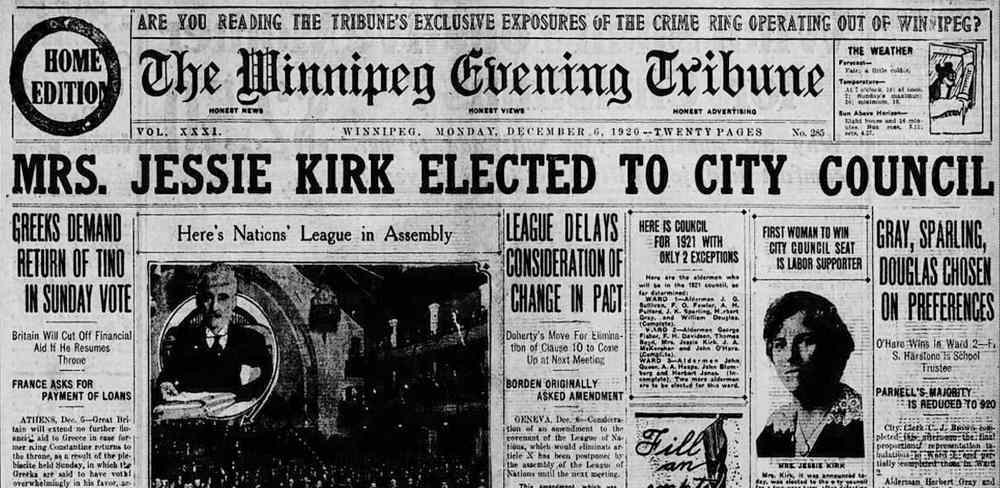

Kirk’s next chance to run for office came later that year, with the Dec. 3 election for city council. She ran as an Independent Labour candidate in Ward 2, which stretched from the Assiniboine River south to the city limits. (At the time, the city had three wards, each electing six members under a weighted ballot system.) She was the only woman to run for council and defeated an incumbent on the sixth ballot, earning herself a two-year term.

At the inaugural meeting of council on Jan. 4, 1921, Kirk was appointed to a number of civic committees, including “improvements” (infrastructure) and public utilities (which oversaw the city’s hydro and waterworks departments.) She was also appointed to the parks board, the public health board and as a city representative on the General Hospital board.

Kirk wasted little time making her presence felt. One of her first orders of business was to open the meetings of the boards and committees she sat on to the public and the media. This included those involving the quasi-corporate public utilities and the private street-railway company, which were sometimes held in camera.

c_

Improving the city’s public transportation was also in her sights. She pushed for improvements, such as a new fare scheme that allowed workers to purchase reduced-fare tickets that could be used at rush hour. She also convinced the street-railway company to provide bus service that would take employees and visitors from the Osborne Street streetcar line to Municipal Hospital (now Riverview Health Centre).

Kirk sometimes found herself on the opposite side of her labour colleagues. In 1921, in front of a packed gallery there to show support for an unemployment-relief delegation, she voted in favour of a grant to assist with the construction of the Soldier’s Relatives’ Memorial on the grounds of the legislature. The boos and catcalls from the pacifists in the crowd were so loud the mayor stopped proceedings and threatened to clear the gallery.

In 1922, Kirk was a member of the finance committee when a controversial $7 wage cut for city employees was being considered. The city was deep in debt from years of recession and, many councillors argued, salaries that had been increased to make up for soaring wartime inflation were never reduced when the cost of living dropped. Kirk reluctantly supported the cut on the condition it apply to everyone on the city payroll, including management, the police department and the mayor’s office, all of which were exempt.

After a number of meetings, many of them quite heated, Kirk was able to get her amendments passed. For her, it was a victory, but not in the eyes of those facing a pay cut.

Kirk ran for another term in the December 1922 civic election, this time as an Independent, with the endorsement of the Winnipeg Taxpayer’s Association. She was defeated by a Labour candidate. It wasn’t until 1934 Winnipeg had another female councillor, author Margaret McWilliams.

Despite the defeat, Kirk remained a political force. She continued to appear before city council, the Public Utilities Board, the police commission and at other meetings to offer her opinion on public policy. In 1923, she entered the temperance debate, touring the province as a leader of the Moderation League, which felt prohibition was an ill-conceived and paternalistic policy.

By the late 1920s, she had teamed up with the Conservatives, and by 1930 was an executive member of the Conservative Women’s League.

Kirk ran for re-election in 1923, 1926 and 1934 but lost each time. Her most interesting campaign was her last one, as her platform, similar to one touted by labour candidates at the time of the general strike, would not seem out of place in 2014.

Under the slogan Home Rule for Winnipeg, she insisted the city had to step back from its heavy reliance on property taxes to pay their bills. Where should the additional money come from? The province.

“I have never been afraid of a fight in all my life, and I am not afraid of a fight with the provincial government to get a share of the taxes, which I consider rightly belonging to Winnipeg,” she said at one meeting.

Though she did not run for city council again, Kirk continued her campaign for “home rule” through the 1930s, presenting the idea before city council committees, the Real Estate Board and the Board of Trade. She also appeared at political forums in subsequent elections to try to get her platform on the public agenda.

Jessie Kirk died in December 1965 and is buried in Brookside Cemetery.

Christian Cassidy writes about local history on his blog, West End Dumplings.