Race-based data a hallmark of pandemic response

Information collected shaped Manitoba’s vaccine roll out

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/06/2022 (1216 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

First-of-its-kind race-based data that was a hallmark of Manitoba’s early COVID-19 response is expected to be used more widely in its health-care system in the near future.

“COVID helped us to establish it could be done,” said Dr. Marcia Anderson, who was public health lead for the Manitoba First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Coordination Response Team and driving force behind collecting and advocating for practical applications of the data.

The data shaped Manitoba’s vaccine roll out, from age eligibility to neighbourhood distribution, and led to the establishment of isolation shelters and homeless and youth outreach.

Combined with employment data, it influenced government policies and prompted the province to give everyone paid leave to get vaccinated. It was the first time race-based data was systematically collected in Manitoba.

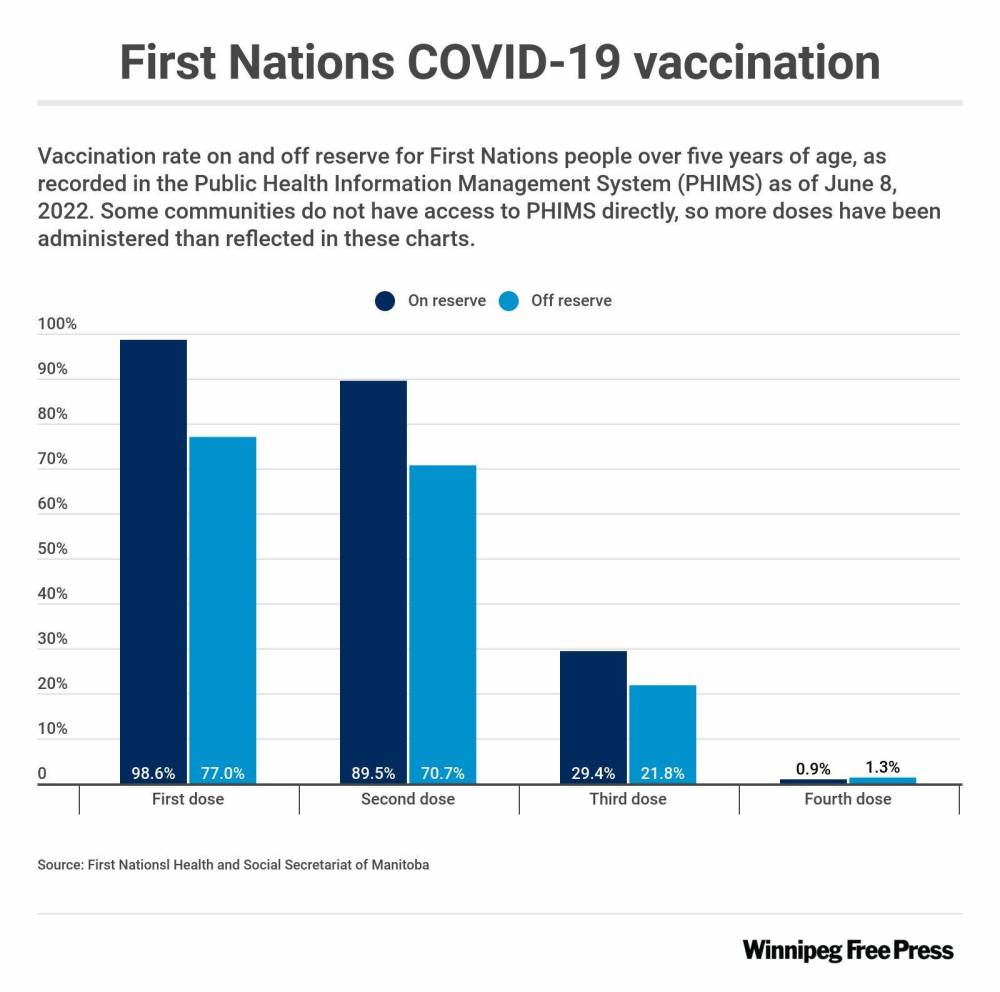

Now, Indigenous agencies are still relying on this kind of information to improve third-dose vaccine uptake and overall health.

They are starting to track positive rapid tests, and are looking forward to a future beyond COVID-19 — one where Indigenous epidemiologists help maintain the “data sovereignty” necessary to improve disproportionate rates of chronic disease among Indigenous and marginalized groups and potentially put an end to systemic racism in health care.

Getting the data in the first place was the result of decades of advocacy by First Nations.

Anderson, now vice-dean of Indigenous health, social justice and anti-racism for University of Manitoba’s faculty of health sciences, said work is ongoing to make sure the data “is available for future.”

A Shared Health spokesperson stated Friday system leaders are looking into how race-based data can inform future health planning.

Manitoba was the first province to roll out vaccine distribution with age eligibility for First Nations set 20 years younger than the general population, based on data revealing First Nations people generally became sicker at younger ages. Other provinces followed suit, after Anderson was invited to present her findings.

In countries such as the United States, Australia and England, collection of racial identifiers as part of health data is much more commonplace, Anderson said.

It’s necessary in Canada, she added, and could have a widespread impact on health. Addressing systemic racism in health care is one of the calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“That is not possible if we don’t have this type of data collection.”

Using the data to tackle lagging third-dose uptake and trying to reach youth in northern First Nations is an immediate priority for Dr. Barry Lavallee, chief medical officer of Keewatinohk Inniniw Minoayawin Inc.

He is leading a project with Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak to visit and survey northern First Nations, some of which already have high vaccine uptake, to better understand vaccine hesitancy.

“Why this project exists is because there is a differential response to sickness and death for First Nations. I think that bears across Canada, but we started keeping the stats over here early in the pandemic, so that we can understand how this evolves as a population,” he said.

Work began in the 1990s to establish info-sharing agreements that would give First Nations control over their own data and research about their communities. Agreements were negotiated between First Nations, the provincial health department, and U of M’s Manitoba Centre for Health Policy in 2017. Those efforts laid the foundation for the formation of a First Nations data working group soon after the COVID-19 pandemic struck in March 2020.

Leona Star, director of research for the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba, has been pushing for good data for the past 10 years. It could have really helped during past health crises such as H1N1, she said.

“What we’ve seen through the (COVID) pandemic is that First Nations have every capability to lead their own pandemic response, if given the proper resources and infrastructure,” Star said.

More resources are needed to continue the work, she said, adding it will be important to consider this kind of data when looking at the effects of so-called “long-haul COVID.”

The secretariat recently helped set up a hot line for First Nations to self-report positive rapid test results, which aren’t being tracked at a provincial level. It will be conducting local data collection in communities over the next three to four years, and working at a national level to set up post-secondary programs geared toward educating future Indigenous epidemiologists.

Star said “data sovereignty” is crucial and First Nations retaining ownership of their data shouldn’t be seen as a barrier to working with governments. Reliance on non-Indigenous research without consultation has historically ignored ripple effects of colonization on health care, and caused more harm, Star said.

“We need data analysts and epidemiologists within every single community. We need our own people trained to be able to do that work.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.