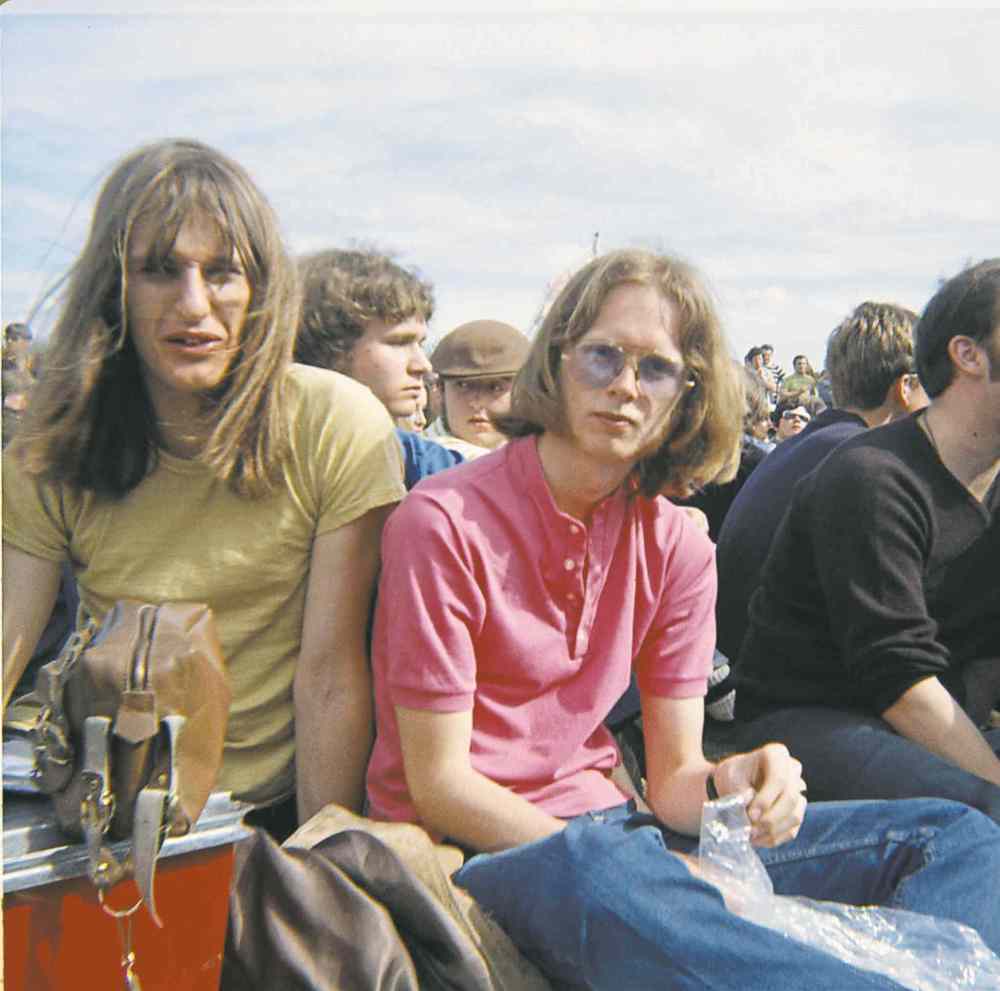

Deluge failed to dampen the fun at the 1970 Niverville Pop Festival

Rock and rain

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/05/2015 (3950 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The pastoral rural community of Niverville, some 30 kilometres south of Winnipeg, boasts a population of roughly 3,500, mostly of Mennonite descent. Many of its residents work in Winnipeg and commute back and forth, transforming the town in recent years from agricultural hub to bedroom community. The town’s lone claim to history is it was home to the first grain elevator in Western Canada.

There is, however, another significant milestone not found in the regional historical accounts, one longtime residents may be less likely to cite. On May 24, 1970, 45 years ago next week, some 10,000 young people descended on a field outside the town for the Niverville Pop Festival. What began as a sun-filled, fun-filled day of music and hippie ambiance (and all that went with it) turned into a mud bath of epic proportions, giving rise to a now-legendary experience. For Manitoba’s budding hippie community, it was their very own Woodstock.

Though the Woodstock movie, with its distinctive split-screen imagery, had yet to première in Winnipeg (it would open at the Gaiety Theatre on Portage Avenue at Colony Street on June 18), the excitement surrounding the three-day festival in upstate New York the previous summer had fired the imaginations of Winnipeg youth. It was inevitable a pop festival would happen here.

Unlike its inspiration, which was initially organized as a for-profit concert event, the Niverville Pop Festival had a philanthropic purpose. The year before, teenager Lynne Derksen fell during a hayride. Her hospital treatment required the use of an oxygenator — a medical device capable of exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood during surgical procedures that may require the interruption or cessation of blood flow in the body. One was flown in from a San Francisco medical facility.

Derksen died from her injuries, but students and staff at the Canadian Mennonite Bible College on Shaftesbury Boulevard established the Lynne Derksen Oxygenator Fund in October 1969 in tribute to her. The goal was to raise $30,000 to purchase an oxygenator for the Winnipeg General Hospital.

“We figured we could make some real money for her by putting on a pop festival,” says Bill Wallace, then of the band Brother.

“So Kurt Winter, Vance Masters and I organized it with another guy, Harold Wiebe. He was from Niverville and got us the land donated for the festival.”

Harold was well-known to the trio for selling 22-kilogram bags of sunflower seeds in local pubs. “We called him ‘Harold the Seed Man.’ “

“Bill was not in favour of organizing a festival to make a profit,” says Wiebe. “It should be for charity. So I told him and Kurt about the Oxygenator Fund. We planned it in my parents’ backyard and initially thought we might do it there, with maybe a few hundred people, but once radio stations started promoting it we knew we needed a big area.”

Wallace recruited the performers, while Wiebe and Brian Toews handled the logistics. Niverville farmer Joe Chipilski donated his uncultivated field 10 kilometres from town, and parking was arranged on a property across the road. Local merchant Wm. Dyck & Sons provided a flatbed trailer for the stage.

The organizers didn’t bother seeking permission from the Niverville community since the festival was being held outside the town. Nonetheless, some of the churches in the area took a dim view of a throng of hippies descending on their community. Local historian Steven Neufeld feels if some members of the community had been aware of the fundraising purpose of the event, they might have had a more welcoming attitude.

“I think that their focus, especially coming on the heels of Woodstock… was the apparent presence of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.” Their perception was not erroneous.

Dozens of local bands, including Sugar & Spice, Justin Tyme, Chopping Block, Dianne Heatherington & the Merry-Go-Round and the Fifth offered their time. The eclectic roster also boasted the Chicken Flat Mountain Boys, Billy Graham’s Jazz Group and folksinger Jim Donahue. My group, the Pig Iron Blues Band, was also on the bill. CFRW DJs Bobby ‘Boom Boom’ Branigan, Charles P. Rodney Chandler and Darryl Provost were lined up to host. Espousing the hippie ethic of the times, everybody pitched in for free.

“We got everything for nothing,” says Wallace. “The only expense was $34 to run the power line in. Garnet Amplifiers supplied the PA.”

Tickets were a bargain at $1, and the show was set to commence at 3 p.m. Sunday.

Organizers anticipated 5,000 attending. By 2 p.m., more than twice that number had taken over the field, spilling onto adjacent fields and clogging the roads in and out. Like at Woodstock, many abandoned their cars by the roadside and walked the remainder of the way. Wiebe and his crew attempted to collect $1 from those who simply wandered in, but it was futile.

“It wasn’t that they didn’t want to pay the $1,” he says, “it’s just that there were too many people coming through the fields.”

“Our whole band, the Weed, minus one, decided to go,” Alex Moskalewski recalls. “We waited for hours on the highway, then longer down some side roads, finally parking in the middle of a field along with a few thousand others.”

Joey Gregorash kicked things off fittingly with the notorious Fish cheer from Woodstock (“Give me an F”). Brother made what would be their last public appearance, as guitarist Kurt Winter had been invited to join the Guess Who the previous week, replacing Randy Bachman (along with another local guitarist, Greg Leskiw). Their set featured several songs later recorded by the Guess Who, including Hand Me Down World and Bus Rider. By the time blues-rockers Chopping Block prepared to take the stage around 5:30 p.m., the sun had been replaced by clouds. What began as a light sprinkle quickly became a torrent of rain and hail. Like Woodstock, the Niverville Pop Festival quickly turned into a mud-fest, as more than five centimetres of rain fell on the site.

“All I can remember,” the late Mongrels guitarist Duncan Wilson was quoted as saying, “was hail a bit bigger than golf balls and lots of mud.”

The rain failed to dampen the communal euphoria.

“I remember everyone really having a lot of fun before the rain,” says Ron Siwicki. “And even when everyone was sitting in their cars in the rain, they were still partying and having fun. It was pretty bizarre, like the spirit of Woodstock transported to Manitoba.”

Vehicles became mired in acres of thick, wet, sticky mud. As local promoter Bruce Rathbone noted, “It took four hours to get four miles through the mud to the highway.”

A Winnipeg transit bus had to be towed out of the mud by a farmer’s tractor. Michael Gillespie remembers, “I had parked my CKY-marked Montego station wagon in a field and got out onto a road only to slide sideways and tip into a ditch. The car was on its side. About 10 people lifted the car out of the ditch back onto the road. Unbelievable!”

Still others simply abandoned their vehicles.

“Roger Kolt went back two days later to get his car and someone had stolen the battery,” says Wallace.

“I wore a brand-new pair of very expensive Italian shoes, which I had just purchased from Holt Renfrew,” Barb Allen remembers. “My feet were so mud-covered I could hardly lift them. The shoes were a writeoff.”

Neufeld witnessed the chaos.

‘I’ll never forget the farmers with their tractors coming to many, many people’s rescue and pulling cars out of the muddy fields’

— Richard Denesiuk

“As a nine-year-old kid, I remember driving past the deluge with my parents and witnessing first-hand cars in the ditch with water up to their windshields,” he recalls. “I remember being shaken by what I saw.”

“There was a certain element of the church population that felt vindicated that the deluge occurred and washed out the event,” notes Neufeld. “The police had been to many of those same homes earlier, warning people about the event, and that for their own safety they should keep their doors locked and closed.”

Despite a general feeling of unease about the festival, the community came together to help out stranded youngsters.

Susan Friesen recalls, “We owned a small hamburger stand with friends of ours called Snoopy’s in Niverville. After the rain, we started getting people coming to Snoopy’s. They were all tired, wet, cold and hungry. We cooked hamburgers, hotdogs and fries. We ran out of everything and borrowed supplies from another restaurant in town called the Pines. We used up all of their fast-food supplies, then called the local grocery store to get more. They were nice enough to open for us. We fed a couple hundred people. We stayed open later than usual, until we ran out of food.”

Others manned trucks and tractors to extricate vehicles trapped in the mud.

“Mr. William Dyck from Wm. Dyck & Sons took his cube van and went to the festival to bring people to Niverville,” Friesen remembers.

Wiebe’s brother commandeered his dad’s tractor and pulled out cars until 2 a.m.

“I’ll never forget the farmers with their tractors coming to many, many people’s rescue and pulling cars out of the muddy fields,” says Richard Denesiuk.

Neufeld relates the story of a local pastor who had expressed his opposition to the festival.

“This particular pastor knew what the right thing to do was in spite of how he felt. He recognized that people were in trouble as a result of the storm. He had access to a large farm truck with a covered box and went and got as close to the site as possible, loaded up his truck with people who were stranded, and took them all back to his tiny home in Niverville,” he said.

“There, he and his wife fed them, helped dry their clothes or got them a change of clothing, tended to their needs and arranged rides for each one back to their homes in Winnipeg and beyond, without accepting any remuneration.”

It was a shining moment for the community.

The event made the front page of the Winnipeg Free Press and the Winnipeg Tribune the following day. It was even the subject of discussion at the provincial legislature, when NDP MLA Russ Doern, who claimed to have been at the festival the day before, announced, “There was a sizeable crowd of young people there who, first of all, participated in the best manner, they were well-behaved, they thoroughly enjoyed themselves, and I think they made this a great success.”

He went on to laud the charitable goal of the event and praised townspeople and local farmers for pitching in when the rain hit. Premier Ed Schreyer suggested perhaps the festival ought to be called a “Tractor Rock Festival.”

Pig Iron never got to play. Instead, I spent several hours pushing my girlfriend’s little blue Ford through the mud, wearing her pink raincoat. With my long hair and pink raincoat, three strapping young lads in the car behind jumped out and exclaimed, “We’ll help you, miss.” They were rather embarrassed to discover the miss was a mister, but nonetheless pushed the car until it was able to get a grip in the mud. I left a pair of shoes stuck in that field. I arrived home late in the evening and went straight into a hot bath.

And what of the money for the oxygenator? “A few days later I delivered $8,000 to the head of the Canadian Mennonite Bible College,” says Wiebe.

Three years later, some $20,000 was donated in Derksen’s name to the Winnipeg General Hospital for the purchase of the machine.

“I barely got to see the bands,” laments Wiebe.

“I was too busy working. It was a lot of fun, although it would have been better had Mother Nature held off for 24 hours.”

Sign up for John Einarson’s Magical Musical History Tours at heartlandtravel.ca.