The long journey ‘home’

Canada's private sponsorship program is heralded around the world, but immigration experts here question why it isn't used more

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/03/2017 (3256 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For the past several weeks, asylum-seekers risking life and limb crossing frozen, snow-covered fields near Emerson have made headlines around the world.

Somali-national Abdirashid Mohamud is also seeking a new life in Canada. He arrived in Winnipeg Tuesday night with no fanfare, only greeted by his uncle.

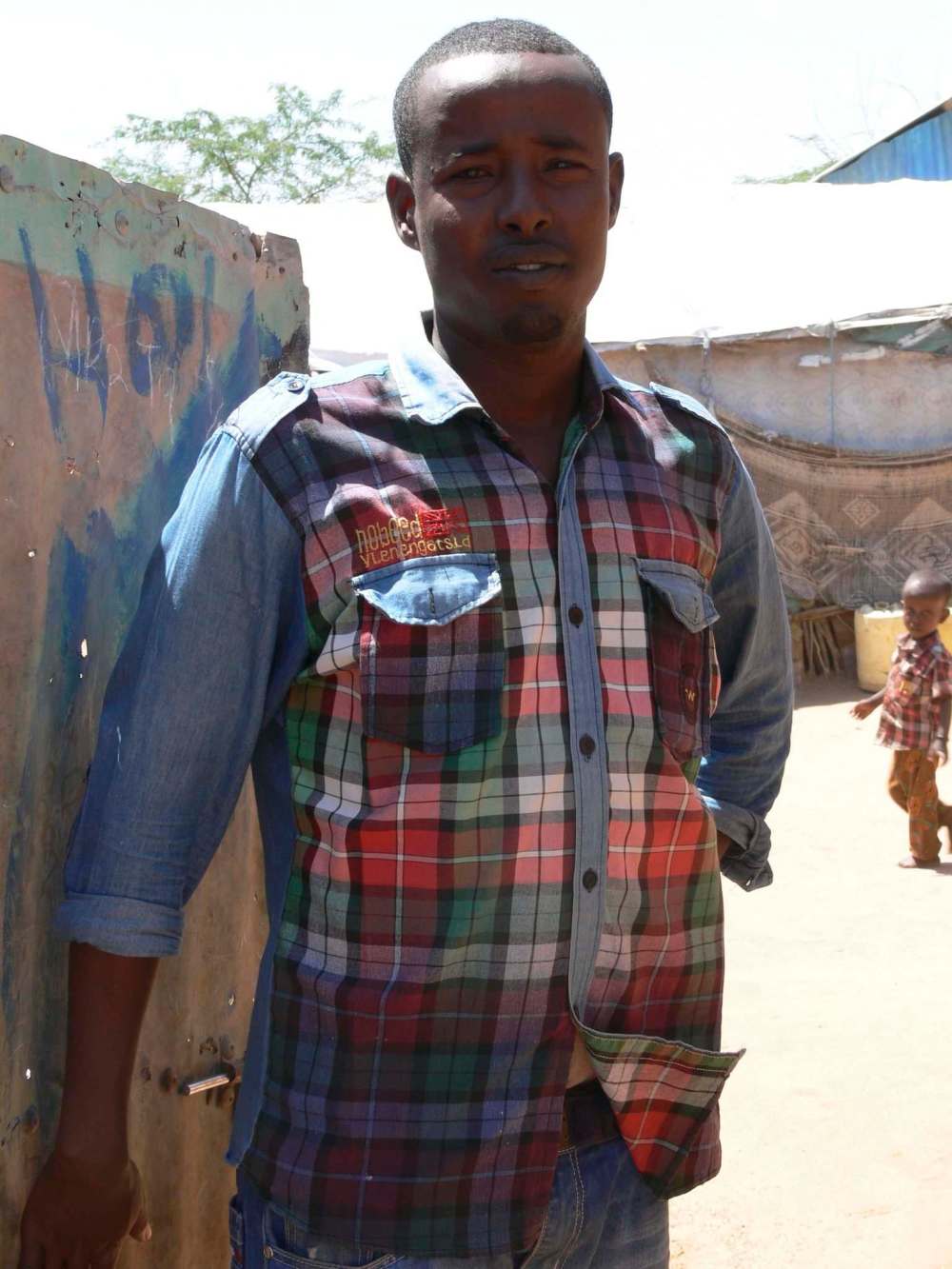

His journey, while also perilous, stands in stark contrast. The 31-year-old spent much of his life in Dadaab — the world’s largest, bleakest and mostly forgotten refugee camp. In 2014, the Free Press visited him at the barren UNHCR site set up 25 years ago for people fleeing the civil war in neighbouring Somalia that’s now “home” to more than 300,000 exiles.

Mohamud finally escaped the camp this week. There was no dangerous journey to the United States and then trudging through frozen fields under the cover of darkness. He arrived safely and in style at the Winnipeg airport Tuesday wearing a Baltimore Orioles hoodie, jeans and a big smile. He made it here safely thanks to an uncle in Winnipeg who sponsored him through our country’s privately sponsored refugee program — a uniquely Canadian program that’s marveled at around the world.

Two months ago, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau boldly tweeted Canada would welcome all those fleeing persecution, terror and war, regardless of faith. Yet, the country’s flagship immigration program is being choked off and left to die, its champions say.

“The system is eroding as the world thinks we are the greatest thing since sliced bread,” said Winnipeg’s Jim Mair, a long-time advocate for the privately sponsored refugee program.

“The number of refugees we can sponsor each year — the number of new ones — is going down,” said Mair, a member of the North End Sponsorship Team, a group of volunteers who’ve been financially and emotionally supporting and resettling sponsored refugees for decades.

Last year, not counting Syrians, there were 10,500 new refugee sponsorship applications allowed for Canada, not including Quebec, Mair said. “That’s dropped to 7,500 this year but the need in Winnipeg alone is probably like 30,000.”

While touting Canada’s 2017 target of 16,000 privately sponsored refugees, Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen, himself a privately sponsored Somali refugee, doesn’t mention that close to half are for Quebec alone, Mair said.

For generations, Winnipeg has been a safe haven for refugees. Once established, they typically send financial support to those left behind until they too can come to Canada. Now the world is seeing the largest migrant crisis since the Second World War along with the rise of anti-immigrant rhetoric with the election U.S. President Donald Trump and similar right-wing populist movements in Europe. So far this year, close to 200 asylum-seekers in the U.S. have risked freezing to death by walking over the border near Emerson to make a refugee claim in Canada.

Mohamud understands their panic. Since arriving in Canada Tuesday night, he’s received a flood of emails from refugees in Dadaab asking for help coming to Canada. Some of them were on track to be resettled in the U.S. until Trump was elected and their dreams derailed.

“Trump refused the refugees,” Mohamud said, who had neither the opportunity nor the money to flee Dadaab earlier on his own.

With a long-term drought, instability, and now famine looming in that part of east Africa, the situation in Dadaab is getting worse, Mohamud said.

He looks about 10 years older and 10 kilograms lighter than he did three years ago when this Free Press reporter interviewed him at his hut in the sprawling, windy refugee camp in northeastern Kenya. He fled to Dadaab after his dad was killed by militia in Somalia, his brother went missing and he became separated from his mom.

Food is even more scarce there today and hope is in short supply, he said Thursday, sampling Timbits and sipping a double-double at a coffee shop on St. James Street.

“The people are very poor and they don’t have much to live for,” Mohamud said, with help from his younger cousin Guled Bashir, 22. Bashir, a Kelvin High School grad, has taken his cousin under his wing and acts as his interpreter.

“He’s overwhelmed right now,” said Bashir, of his cousin dealing with jet lag and culture shock far from the bare, orange desert sand of Dadaab and its dangers. “He came from a different place.”

That place has been under attack from Al Shabaab terrorists on one side and hostile Kenyan government forces who want the refugees gone on the other. The occupants are not allowed to erect permanent homes in the camp. Nor can they leave for jobs elsewhere in Kenya. Mohamud worked for an uncle who ran a makeshift electrical shop in the oldest section of the refugee camp, learning the hard way and getting a few shocks.

Mohamud still wants to be an electrician, but he says he will spend his first few months improving his English.

Returning to Somalia is not an option for people in Dadaab, said Mohamud’s uncle and sponsor, Abdi Ismail. Somalia is overrun with criminal gangs, and there’s no stable government, security or civil society.

“Some people tried to go back but they couldn’t take it,” said Ismail, who arrived in Canada more than a decade ago as a government-assisted refugee from Dadaab. In 2010, he applied through Hospitality House to sponsor his nephew in Dadaab.

Mohamud heard nothing from the Canadian government for six years until last April. He was told to board a special International Organization for Migration bus that travelled from the camp to Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi for an interview with a Canadian visa officer. The day — April 19, 2016 — is one he will never forget.

“She was very nice,” he recalled of the women who held his fate in her hands.

After questioning him at length and reviewing his documents, she told him he was approved to go to Canada. He was stunned. “I stood up — I’m very happy and excited.” He thanked her and returned to Dadaab to await further instructions.

That wait lasted almost a year. When the travel arrangements were made and he was finally leaving Dadaab, Mohamud said he wasn’t sad to go. Flying to Canada where family would welcome him felt like winning the lottery.

“I’m happy to go!” he said in English with a huge smile, waving and laughing while replaying his Dadaab departure: “‘Goodbye! Goodbye!’”

Mohamud was one of the world’s 65.3 million refugees in need of a safe place to call home and set down roots. Many countries that want to help them are looking at the success of Canada’s private sponsorship program that brought Mohamud here.

In December, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the federal government held a conference in Ottawa with representatives from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the U.S. to talk about Canada’s private sponsorship model and how it could be adapted and supported in other countries.

“Canada boasts about its PSR (privately-sponsored refugee) program but it’s merely a fig leaf covering the reality that we’re hardly doing anything,” said Hospitality House Refugee Ministry’s executive director Tom Denton.

The federal government isn’t tapping into the program’s enormous potential for boosting Canada’s economic growth and reuniting families separated by war, famine and disaster, he said.

Last year, the faith-based charity responsible for the most private refugee sponsorships in Canada prepared a waiting list to see how many refugees Winnipeggers wanted to sponsor. In just a few weeks, the Hospitality House list had 30,000 names on it.

The federal government, however, has been cutting the number of new applications for private sponsorship while Canadians who want to support the program — and the global prestige of having it — grows, said Mair with Winnipeg’s North End Sponsorship Team.

“Across the country, it’s huge — probably 100,000,” said Mair. “They’re never going to give us that.”

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

Carol Sanders

Legislature reporter

Carol Sanders is a reporter at the Free Press legislature bureau. The former general assignment reporter and copy editor joined the paper in 1997. Read more about Carol.

Every piece of reporting Carol produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.