What went around came around

The Forks: from meeting place to lawless shanty town to rail yards to meeting place again

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/04/2020 (2109 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The idea that everything comes full circle and eventually returns to its origins is certainly true about the heart of our city.

Though the space is eerily empty now — closed until further notice due to the COVID-19 pandemic — The Forks is Winnipeg’s meeting place par excellence.

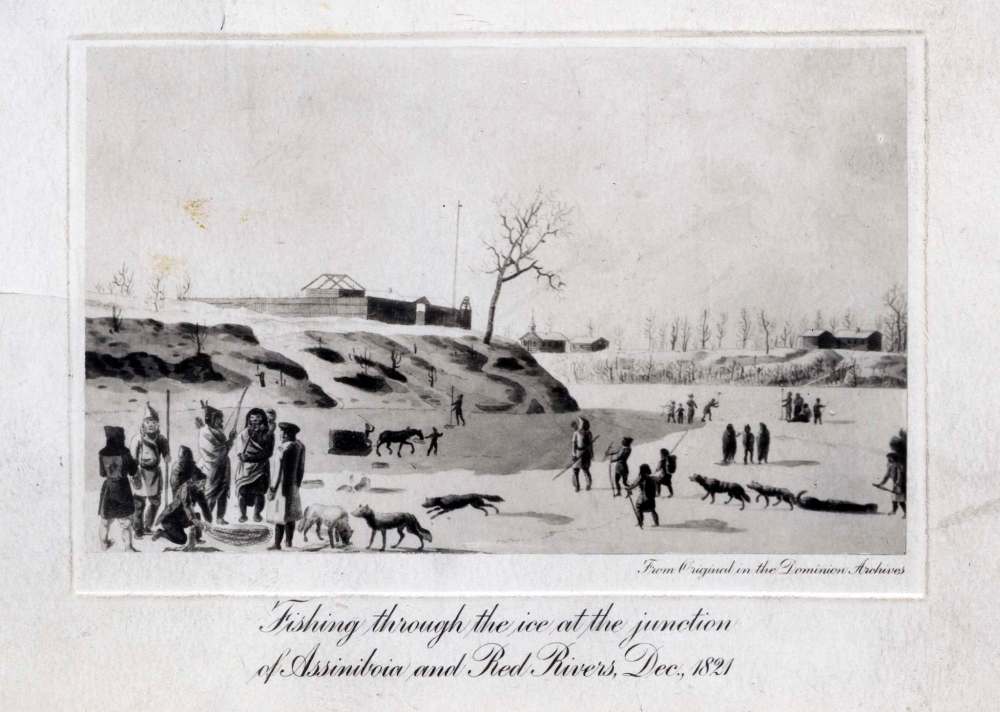

It was such even thousands of years ago. The confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers was a hub for commerce, trade, and meetings between Indigenous groups including Assiniboine, Cree, Dakota, Oji-Cree and Ojibwa. The space has been occupied for nearly 6,000 years, The Canadian Encyclopedia says.

Late last year, as Free Press columnist Niigaan Sinclair reported, archeologists uncovered evidence supporting long-told Indigenous oral stories of a massive meeting at Nistawayak — Three Points, the original Cree name for The Forks — in or around the year 1285. The oral stories told of a gathering of 10,000 people where, after weeks of meetings, a peace treaty covering vast areas of what are now the Dakotas, Manitoba, Minnesota, Ontario, Michigan and Wisconsin.

The Forks was also a landing place for fur-trading settlers and the core of a valuable water route. Explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye arrived in 1734 and established the Fort Rouge trading post; the Hudson’s Bay Co. established Upper Fort Garry in 1835 and the Red River Colony burgeoned.

Later that century, The Forks was a site of conflict, a key location in the Red River Rebellion. Louis Riel and his Métis supporters seized Upper Fort Garry in November 1869, and established the Convention of Forty, which demanded that the federal government — which wanted to annex the territory for Canada — negotiate with the Red River Colony and grant settlers property rights, the right to an elected council and a railroad to the east, among others.

The railroad indeed came. Ironically, unprecedented railway development pushed people out and caused The Forks to lose its identity as a meeting place.

By the time Sir John A. MacDonald’s transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway reached Winnipeg in 1881, the area surrounding The Forks had turned into a lawless shanty town called the Flats, occupied mostly by new immigrants and refugees. It was, as Winnipeg historian Randy Rostecki described in a piece for the Manitoba Historical Society, “a zone of urban poverty and vice… isolated in a social as well as physical sense at that time.”

It was perhaps for that reason any economic development of the Flats was seen as a positive. As Rostecki noted: “emptiness was a waste to minds used to projecting monetary value onto a commodity such as land.” No fewer than four railroads occupied the space at some point in the near-century that followed.

In 1889, the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway erected workshops, a station and engine and freight sheds between the Assiniboine River and Water Avenue (modern-day William Stephenson Way.) The NPR even built a palatial hotel, the Manitoba.

However, the Manitoba burned down in February 1899 and the Canadian Northern Railway entered the picture shortly after.

“Throughout 1903, it was obvious that the CNR was planning something, although (railway baron) Donald Mann only allowed delectable tidbits to leak out,” Rostecki wrote. “In November of that year, the Manitoba Free Press published a map showing the Flats entirely in the hands of the CNR as a rail yard, with all the streets cancelled and Fort Garry Park passing into oblivion.”

CN, along with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, completely redesigned the area and cut it off to the public. By November 1912, the East Yards, as it was known, was virtually complete as more freight sheds were erected and Union Station built a year prior.

The 93 acres now occupied by The Forks Market, The Johnston Terminal, Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and Shaw Park remained industrial for more than 60 years thereafter. After CN built the Symington Yards in 1962, the East Yards waned in importance and became used mostly for freight and passenger car storage. It was, “once again a sleepy backwater similar to its forebear, the Flats,” Rostecki wrote.

CN began actively looking to sell the East Yards in 1973, as by then it was only being used at 25 per cent capacity, Free Press urban reporter Frances Bidewell wrote that year. CP was also willing to relocate their tracks, contingent on a cost-sharing agreement. In 1974, the federal government designated land on the banks of the Assiniboine and the Red as The Forks National Historic Site.

However, it would be 15 years before The Forks as a destination was realized. In 1975, a city task force recommended the land be used as a combination of housing and public recreation space, but was criticized by then-councillor Bill Norrie as being “very negative.”

Nonetheless, the report planted a seed in proposing something unique. “It is necessary to restrict the development of the East Yards to uses or configurations which would not normally be expected to locate in the existing downtown,” the report read. That meant no office, retail, or hotel components that would “compete with existing and prospective downtown establishments.”

In 1978, the federal and provincial governments came to an Agreement for Recreation and Conservation, “a $13-million pact to preserve the natural, recreational, and heritage resources of the Red River Corridor… (including) $2.8 million for acquisition of land for a visitor or interpretive centre at The Forks.”

Interestingly, one such idea floated the same year of the ARC was to build a new 20,000 seat arena for the WHA’s Winnipeg Jets, who would enter the NHL the year after. This idea received a “frigid first hearing” from city officials, with councillors calling it “premature, iffy, and too conditional.”

By 1984, nothing had been done. The redevelopment project was snarled in bureaucratic red tape.

That year, Free Press writer Val Werier advocated the feds “bequeath this historic land to Winnipeg” and wrote it was “time the city or province (acted) with some vision and leadership to acquire the land from CN at no cost.” By April, CN was prepared to give eight to 10 acres so Parks Canada could begin to build the interpretive centre “on the condition it participates in any future development agreement.”

That idea was rejected by Norrie, then mayor, who explained if the city was unable to acquire the land for themselves, they’d have to be involved in development with CN. “We don’t want a partner in the form of a railway,” he said.

Werier called for something “creative and dramatic.”

“The land should be utilized as an urban space for recreation and social intercourse the year round,” he wrote. “The possibilities are tremendous on this land, only a few minutes’ walk from Portage and Main, but now obscured and unknown to most people who frequent downtown.”

In 1987, the land ownership and the dizzying array of issues of who had to buy what from whom were finally sorted out. The Winnipeg Core Area Initiative obtained 58 acres from CN in a tri-level agreement.

The WCA’s offshoot, The Forks Renewal Corp. — which merged with the North Portage Development Corp. in 1994 to form The Forks North Portage Partnership, which owns and manages The Forks to this day — was formed to revive the site.

The community-based Forks Renewal Corp. was given $20 million to transform the site, starting at the rivers’ junction. They conducted archeological digs, constructed roads, and revamped historic railway buildings — all while thinking what type of recreation, housing, and commercial facilities they could build as they moved north. They even ran ads in the Free Press, asking citizens for their input.

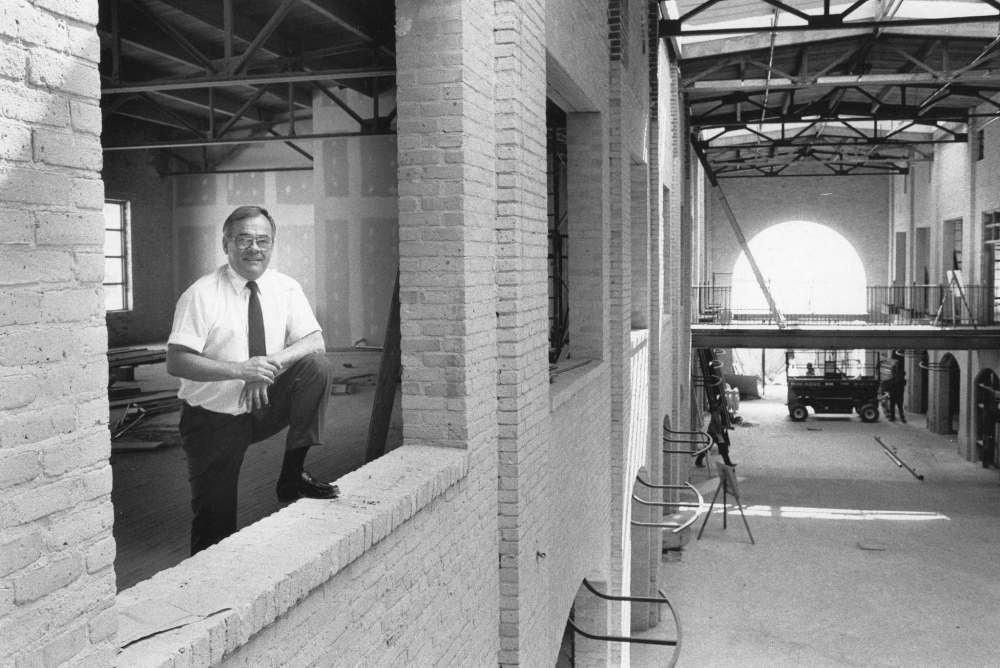

Bringing “decaying buildings up to par,” while retaining as many of their original elements as possible, began in June 1988 and was quite the task. Project co-ordinator Kraft Construction even took down all the bricks from the 81-year-old former CN horse stables — which now houses The Forks Market — and cleaned them all by hand.

The Market was inspired by Vancouver’s Granville Island Market, Free Press writer Randal McIlroy wrote in June 1989. Amenities on opening day included produce shops, delis, bakeries, cheese mongers, espresso bars and sushi restaurants. Most vendors were “mom-and-pop” efforts.

“It’s more than just a market,” Forks Renewal Corp. president Nick Diakiw was quoted as saying a few months prior to its opening. “It’s got to be a total experience. There’s going to be programming… so that you can come to the market not only to shop but to be entertained, to be part of an activity that’s happening.”

“In addition to the potential afforded by such an expanse of riverfront property, there was a sense of reclamation,” McIlroy wrote. “The epicentre of this city’s initial growth, and a meeting place for many years before that, the river junction was an invaluable historic site, made inaccessible by industrial development.”

The Market opened on Oct. 5, 1989, with general manager Randy Cameron estimating at least 10,000 people would pop by.

“I could have had all kinds of fashion tenants or beauty salons or dry cleaners…” he said on the eve of opening. “To do that would be to make it a shopping centre. But we don’t need that. There’s enough shopping centres in town.”

Aldo Santin wrote the next day “rain drove the opening ceremonies indoors but it didn’t dampen the enthusiasm” of the elbow to elbow crowd, who enjoyed powwow singing and dancing, French fiddlers, jugglers, food, drinks and artisan stalls.

It’s safe to say Diakiw and Cameron’s visions were realized. The historic site continued to evolve; The Johnston Terminal, Manitoba Children’s Museum, Oodena Circle, The Plaza Skateboard Park, the CN Stage and Field, and CMHR were all added in the years that followed. The Forks attracts more than four million visitors per year — Winnipeggers and people from around the globe alike.

Although The Market is decidedly more chic and urbane since the large-scale renovation that began in 2015, The Forks has not lost its raison d’être. It’s a vibrant place that connects people of all ages, ethnicities, and walks of life.

It’s a place that will, in the future, bustle again. The din of good craic and conversation, had over delicious food from local vendors — Nuburger, Red Ember, Tall Grass Prairie — and drinks from The Common, will eventually return. People will stand, necks craned upward, to see fireworks displays light up the sky. Bands will rock out on the CN Stage in front of throngs on the field.

Those will be glorious days, a future possible because enterprising people saw an unprecedented opportunity in the form of a tract of land and took it.