Human rights and learning to read

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

It’s a human rights issue, plain and simple.

A report released late last month by the Manitoba Human Rights Commission makes clear the province is failing young students and their families by not providing adequate assessment and supports related to basic reading skills.

And reading, the report declares, is as fundamental as education gets.

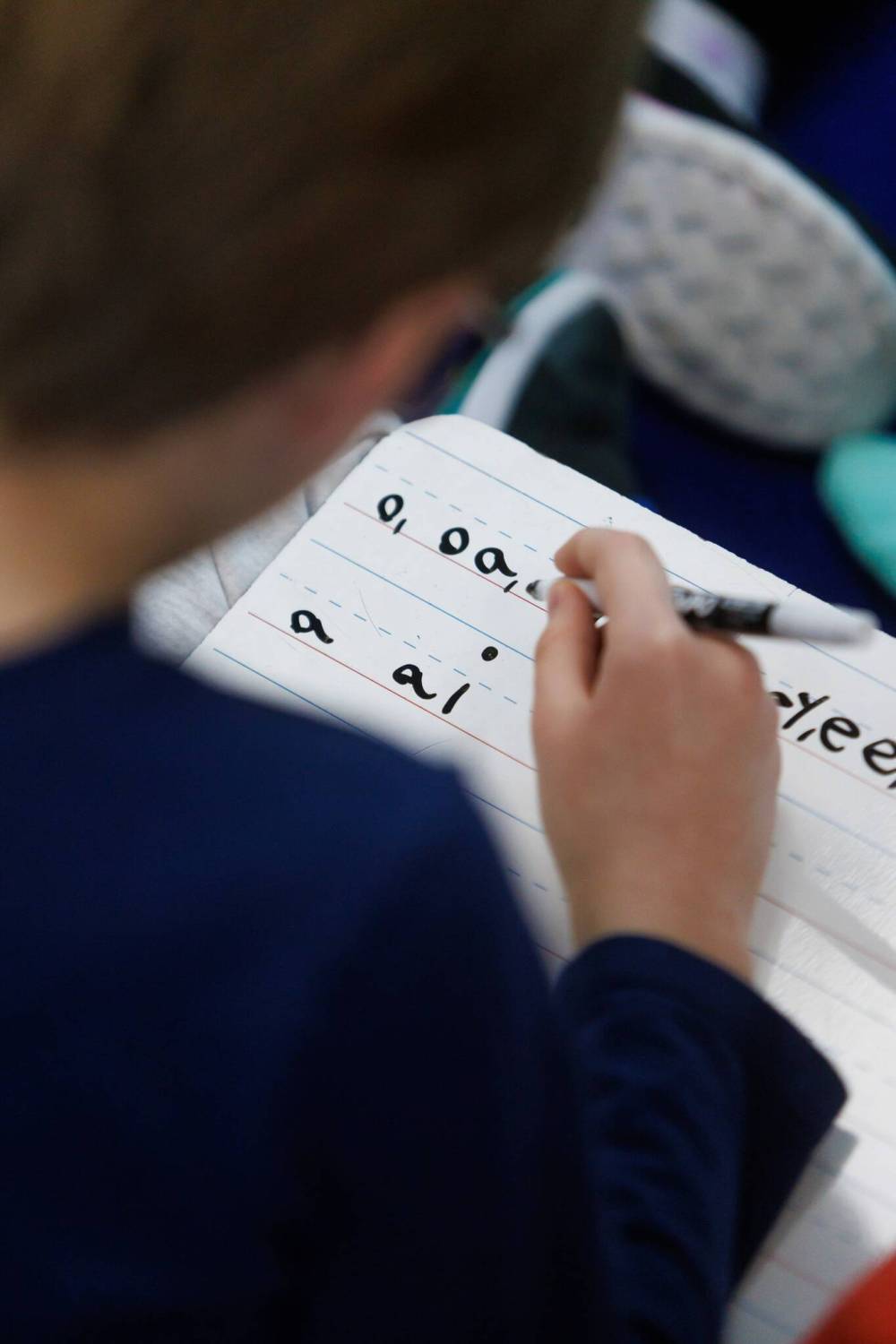

MIKE DEAL / FREE Press files

Basic reading skills are fundamental.

“Reading is the foundation of learning and a fundamental skill that shapes every aspect of life,” the document’s executive summary states. “Students who cannot read well are more likely to face challenges in school, work and everyday life. When students cannot access reading instruction, it affects their confidence, mental health and long-term opportunities.”

The problem, it seems, is that many Manitoba schools long ago abandoned the evidence-based methods for teaching that were, for decades, the baseline technique for reading education. Rather than relying on “structured literacy,” which focuses on phonics and relating sounds to specific letters and letter combination, many schools had opted for a more “modern” style of teaching that emphasizes exposure to a variety of texts featuring different topics and increasing levels of complexity/difficulty.

Without a grounding in the phonics-related connection between letters and sounds, however, many students have fallen behind. And the schools that were supposed to be teaching them how to read have failed to adequately recognize when they couldn’t, and therefore were unable to determine why and provide opportunities to catch up.

The risks are not evenly distributed across the education system. Owing to a number of factors, both individual and more broadly socio-economic, some groups are at greater risk of falling behind than others: students with reading disabilities, including dyslexia and other related challenges; students living in poverty; BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of colour) students; and, students learning English as a second language while also contending with the rest of the curriculum are at greater risk of not meeting basic reading standards.

“I didn’t get taught the right way and it made my reading worse,” said one nine-year-old student interviewed by the Free Press for a feature story examining the commission report’s findings.

“It was really hard because I felt really sad. Sometimes, after school, I came home and cried in my bed because I was so sad because I didn’t know what to do.”

Her story is, lamentably, not uncommon, nor are the revelations of numerous parents who described hundreds of hours and many thousands of dollars spent on private tutoring aimed at getting their kids’ reading level up to the grade-appropriate standard they wrongly assumed in-school teaching would achieve.

The report, titled ‘Supporting the Right to Read in Manitoba: The ABCs of a Rights-Based Approach to Teaching Reading,’ represents the first phase of a two-part analysis of literacy education in this province. Its eight recommendations should be quickly considered and adopted by the provincial government and throughout the education system it oversees.

This isn’t a philosophical debate over which of the currently available reading-education techniques is best, seeking a compromise that satisfies the inclinations of various schools of thought. It’s about ensuring young Manitobans are given the best chance of acquiring the reading skills that will allow them to succeed as adults in an ever-more-challenging world.

The commission has laid the groundwork, but the report’s authors have clearly stated they are human-rights professionals, not educators. Whether this report and its expected followup will have the desired impact will be determined in the province’s classrooms.

As the report implores, “Ensuring that all children are given a fair and equal opportunity to learn to read is a matter of human rights, dignity and equality.”