Economic inequality at root of Winnipeg General Strike

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/06/2012 (4855 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

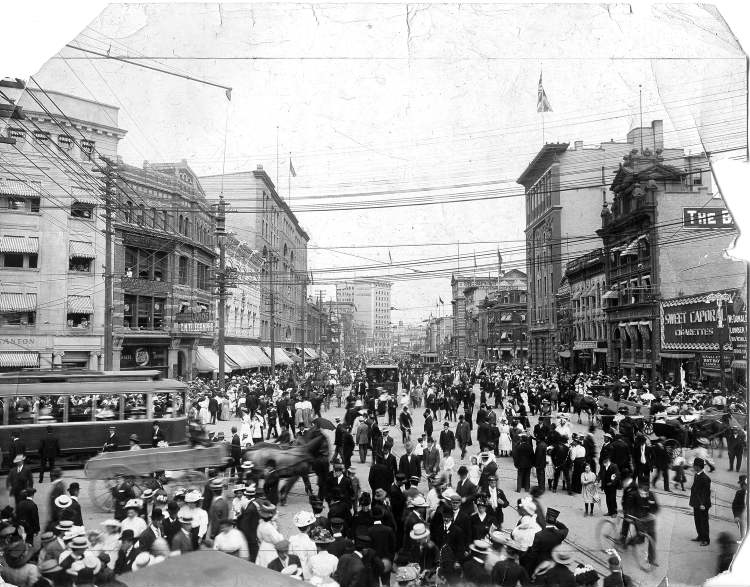

When the workers of Winnipeg went on strike, the newspapers went on the offensive: “Bolshevism invades Canada,” screamed the New York Times.

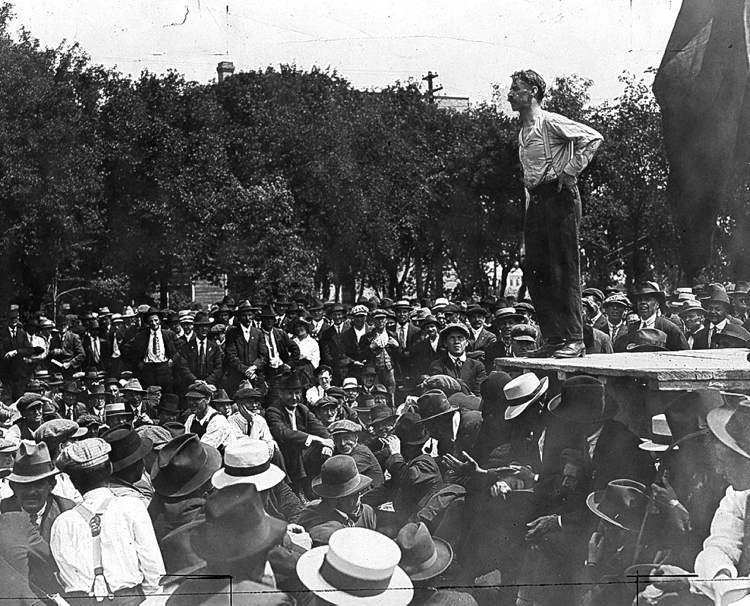

But for most of the men and women who streamed out of the warehouses and onto the streets, the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike was not an exercise in ideology. Instead, its roots grew from a yawning chasm of economic inequality that had become too impossible to ignore.

When spring came that year and the snow melted into the mucky streets of the North End, the city was restless. The world was gasping for breath in the wake of the Great War.

Soldiers returned home from the trenches looking for work, but there was little to be had. Those who could find work gathered in fraternal halls to cry out in frustration at wages that limped behind a soaring cost of living.

In his testimony before the 1919 Royal Commission on the roots of the strike, Trades and Labour Council president James Winning spoke of a provincial report that found a single woman needed $12 a week to maintain a decent life. In the slums of Winnipeg, working men tried to feed families of five on as little as $18.

Meanwhile, postcards from the time show sleek black automobiles cruising down a groomed Wellington Crescent, the shapes of mansions looming from beyond neatly trimmed trees. For the poor of the time, whose bodies ached from the labour of 14-hour days, a growing awareness of how their employers lived festered like an open wound.

“Winnipeg unfortunately presents a prominent example of these extremes,” Hugh Amos Robson wrote in his 1919 Royal Commission report on the causes of the strike.

“There has been… an increasing display of carefree, idle luxury and extravagance on one hand, while on the other is intensified deprivation.”

When the tension finally snapped, what exploded forth was a historic labour protest and one of the biggest social resistance movements Canada has ever seen. On May 1, construction and metalworkers walked off the job, demanding higher wages; on May 15, after employers refused to negotiate with two umbrella unions, the women who worked the city’s telephones walked off their shift; nobody came to replace them. Within hours, almost 30,000 workers had joined the strike. It was almost the entire workforce of the city.

For weeks, everything stopped — except for protests, arrests and a fractious war of words waged by newspapers. When all was said and done, the strikers held out for 40 days.

Most of those days were peaceful, but that was shattered on June 21, 1919, when 25,000 workers flooded downtown for a planned march. It would become a powder keg. A streetcar wound through the crowd, which flipped it into the street; Winnipeg Mayor Charles Gray read the riot act. There was a gunshot, a warning shot from the Royal Northwest Mounted Police. Then, there was panic, a stampede of people, the blur of police truncheons.

By the time Bloody Saturday was over, one man — Mike Sokolowski — was dead of a gunshot wound. Another died in hospital a few days later.

On June 26, strike leaders called it off. The Winnipeg Telegram smugly declared the strike’s “dastardly attack” had been “a miserable failure.”

But its legacy endured: both as a watershed, and as a warning. In his commission report, Robson recommended the government explore ways to open education to the poor, to introduce better wages and working conditions for labourers and to improve access to medical treatment. He called for taxes on the wealthy to help pay for initiatives to improve the lot of the poor.

“It is necessary that steady labour should see that it has the consideration from the government and other elements of the population, and that such consideration takes practical form,” Robson wrote.

“Otherwise, it is not likely to remain silent.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.