RCMP ‘mismanaged’ Pickton case: report

Says lives could have been spared

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/08/2010 (5516 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

VICTORIA — A draft copy of the Vancouver Police Department’s internal report on the investigation of Robert Pickton confirms that police had compelling evidence pointing at the serial killer by August 1999 — more than two years before his arrest.

But because of jurisdictional battles, bad management, and shoddy analysis of the information, police turned their backs on Pickton, while he continued to take women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and murder them on his Port Coquitlam, B.C., farm.

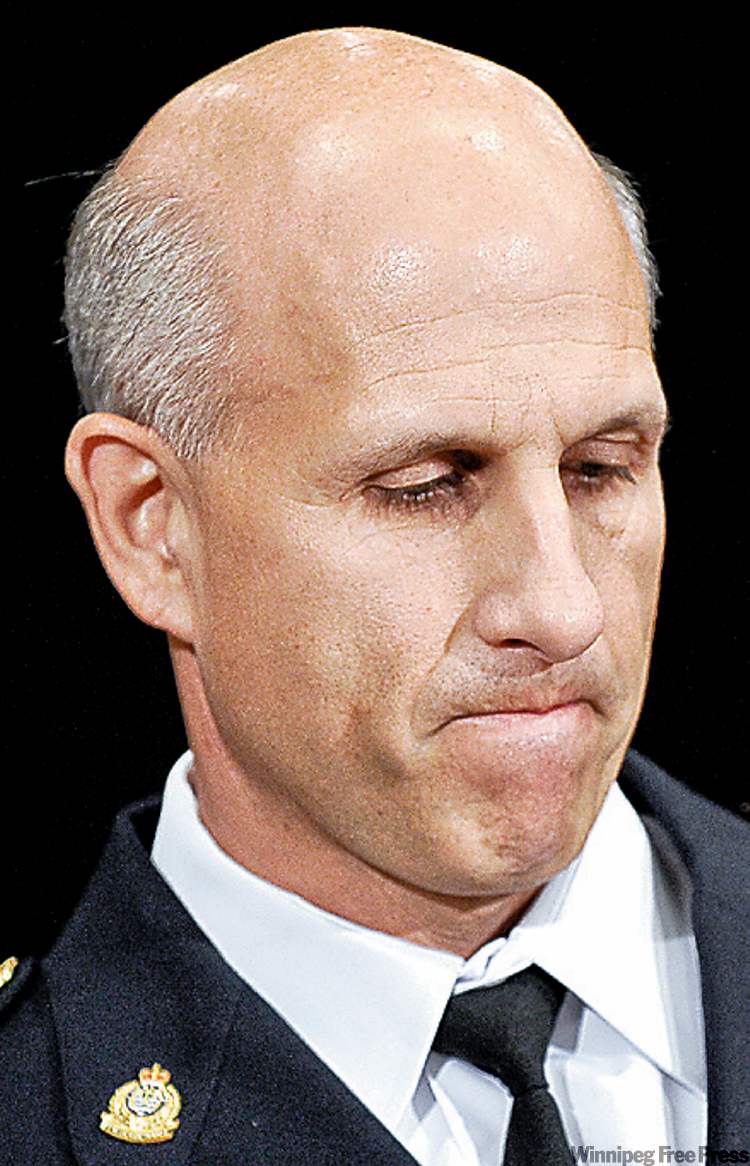

The botched investigation took a heavy emotional toll on the Vancouver police officers who worked on the file and believed that Pickton was a viable suspect, the report by Vancouver deputy chief Doug LePard says.

"But the impact on the investigators and the VPD pales in comparison to the tragedy that could potentially have been averted," LePard says. "After August 1999, 13 more sex-trade workers went missing, and DNA and other evidence connects 11 of these women to the Pickton property."

LePard pulls no punches against his own department — particularly senior managers of the day — for failing to recognize sooner that a serial killer was preying on sex-trade workers. The reluctance to commit to the theory meant that front-line investigators and managers never got the resources they needed to handle such a difficult case, LePard concludes in the report.

The draft copy, obtained by the Victoria Times Colonist Thursday, is labelled "privileged — confidential draft prepared in contemplation of civil litigation."

The members of Vancouver’s Missing Women Review Team "performed in what could fairly be described as a heroic manner in the face of great adversity," LePard writes. But it’s clear from the report they were often working with one hand tied behind their back. Still, LePard lays most of the blame for the failure to capture Pickton sooner at the feet of the RCMP, which took the lead because Pickton lived in their jurisdiction, where the murders were suspected of happening.

"Ironically, even had the VPD’s Missing Women Review Team been a model of investigative excellence, it would likely have made no difference because the investigation into the information about Pickton was the responsibility of the RCMP in Coquitlam," he says. "That investigation failed because it was mismanaged by the RCMP, who controlled it."

LePard notes that by August 1999, police already had:

— knowledge that Pickton had been charged with trying to kill a prostitute at his farm in 1997, although the charges were later stayed;

— a male source telling them of a woman who had seen bags of bloody clothing and women’s identification in Pickton’s trailer;

— three sources telling them, independently of one another, about a woman who claimed to have seen Pickton with a butchered woman hanging in his barn;

— the woman’s denials which, LePard says, were "utterly lacking in credibility;"

— one source telling them he had seen handcuffs in Pickton’s bed, that Pickton had a "special" freezer in his barn, and that he served strange meat that the source came to believe was human.

"Taken together, the investigators clearly had sufficient information to justify an aggressive investigation into Pickton," LePard concludes.

Instead, the provincial Unsolved Homicide Unit got involved and decided that the information of one of the key informants was not credible.

Little was done on the file again until the RCMP conducted an interview with Pickton in January 2000 — an interview, which LePard says "was not well done."

Pickton was allowed to have a friend present, the interview wasn’t properly planned or executed, and police failed to follow up on Pickton’s consent to let them search his property.

Pickton wasn’t caught until a rookie RCMP constable, unconnected to the missing women investigation, got a tip about weapons on the farm and got a search warrant in February 2002. It was during that search that police stumbled upon identification and a prescription inhaler linked to two of the missing women. Pickton was subsequently charged with the murders of 27 women, and convicted on six of those.

— Postmedia News