It’s the kind of face many fear

Ex-NHL player knows what First Nations people endure

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/10/2011 (5093 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

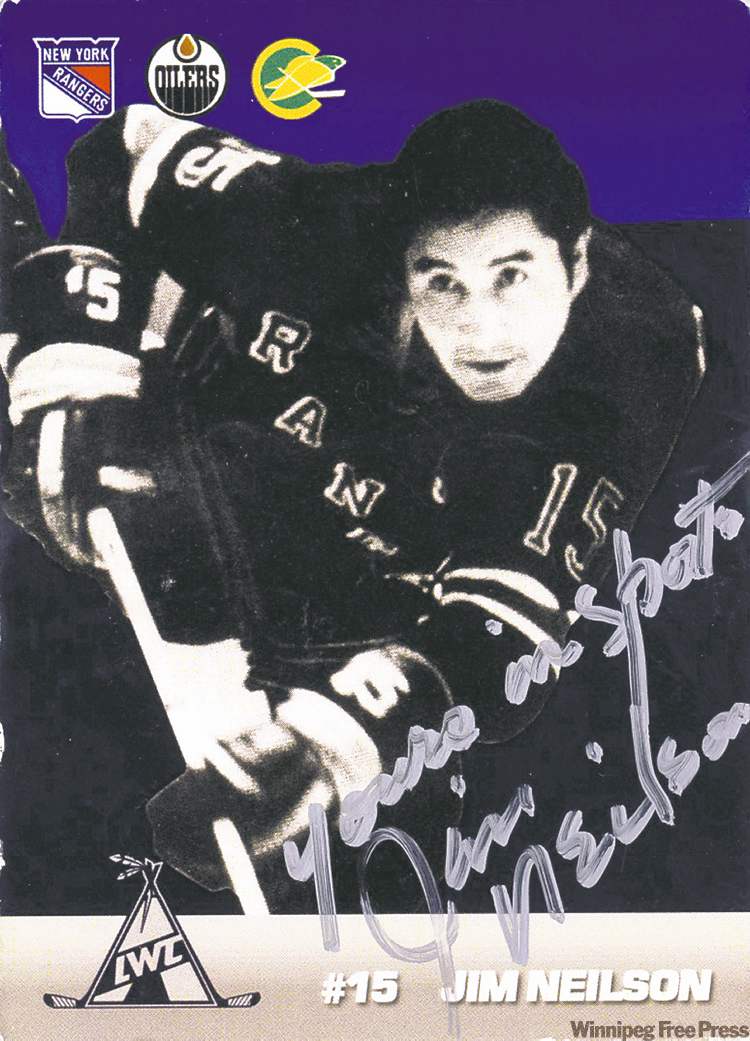

Jim Neilson has the sort of face that seems to frighten so many Winnipeggers.

Kind, gentle and, in his case, still handsome, even with a bent nose, even as he nears his 70th birthday. It’s the sort of classic, strong-featured First Nations face that’s similar to the faceless “1,000 people” Air Canada executives in Montreal recently decreed were too frightening for their overnighting flight crews to deal with in downtown Winnipeg — even at a hotel that’s a slapshot away from where the new Winnipeg Jets will make their regular-season return to the National Hockey League on Sunday.

In fact, in Jim Neilson’s case, the only people who ever deserved to be afraid of him were the NHL forwards the 6-2, 210-pound defenceman used to level during 17 years as a pro hockey player, a dozen of them with the New York Rangers.

He played his first game against Gordie Howe and his last game as a teammate of Wayne Gretzky with the WHA Edmonton Oilers. But you can look all that up.

The story I want to tell is about how Jim Neilson got from Big River, Sask., to the Big Apple, New York. And how he has since come to walk the streets of downtown Winnipeg, usually by himself and virtually unrecognized. Like an old Lone Ranger who doesn’t need a mask, but wears one anyway.

— — —

It’s Thursday afternoon in his downtown apartment and we’re talking about his recent diagnosis of prostate cancer, the Jets’ return and how he’s happy for the city. Although he doesn’t watch hockey much anymore.

“Sometimes if I’m having a beer and there’s a game on at the bar, I’ll watch.”

With that, Jim offers me a 7Up and grabs an ice-chilled Blue for himself. Curiously, that’s how we originally met in the early ’80s — over dressing-room beers during our weekly, no-raise, no-contact shinny games at the River Heights Arena.

Back then, he seemed happy to play a casual version of a game he hadn’t experienced since he was a kid in a Catholic-run orphanage in Prince Albert, Sask. That’s where his Danish-born father placed him and his two younger sisters when their Cree mother left the family.

“He figured the best place for me to go was the orphanage.”

His father was a trapper who lived in the bush. What else could he do with three motherless children under six?

Jim says he never really knew his mother. He never really got to know his father, either.

His dad visited once a year, and as far as Jim knows, never saw him play hockey at any level.

“Eventually it was awkward, because the orphanage was my life,” he remembers of the visits. “It was good to see him, but this was my family now. You had all the other kids to play with.”

Most of them were white.

Now that he knows more about how First Nations children were treated in Indian residential schools, Jim reasons that he was fortunate to be left at the orphanage instead of the Indian residential school next door.

Fortunate to have a refuge like the outdoor hockey rink and all that time to develop his natural gifts playing “hog the puck,” even if he never felt like he had enough to eat.

Fortunate that a nun named Sister Ignatius would sometimes sneak him sandwiches and take an interest in his hockey.

“I do have an understanding of what could have been if I hadn’t gone to a white school.”

He feels fortunate, too, that when he was languishing unnoticed on the bench as a junior, injuries to other players forced the coach to put him on defence. Suddenly he was in his natural position, and a Ranger scout named Johnny Walker took notice.

Still, there’s been a personal price to pay for all the good fortune, in particular all the years at the orphanage.

“I didn’t know what I was, to tell the truth. I was just there.”

He says he’s never seriously delved into his native background, even after Phil Fontaine hired him to be part of a short-lived aboriginal economic development program and he moved to Winnipeg in 1984.

So back at the orphanage, he cheered the cavalry instead of the Indians, shrugging off the “wagonburner” comments the way he would learn to shrug off crushing bodychecks — as if they didn’t hurt. And later, starting in junior hockey, he would be given the supposedly benign label of “The Chief” that he would wear for the rest of his life.

And now?

He says he feels guilty about not doing enough for aboriginal kids who might have the kind of natural athletic gifts he had, but no structure in their lives and no one to care for them the way Sister Ignatius did.

Then he alludes to a man he sees downtown near the MTS Centre, a panhandler who has only one hand.

“I’m always trying to give him a couple of bucks.”

I sense that Jim feels guilty about the panhandler, too. And all the other faces like his own that people don’t want to look at. So I ask if he ever notices people looking at him as if they’d rather not see him.

“No,” he says.

But then he mentions how he can see the reaction of people toward the panhandlers and how he reacts.

“I just walk down the street. Strut down. I know where I’m going. I know what I’m going to do.”

Where he’s going the next day is to Oakville, Ont., to spend Thankgiving with Darcy, one of his two daughters. And perhaps later next spring, after he and his doctor sort out his prostate cancer treatment, he’s planning to move to Saskatoon, where his son David lives. “It’s a nice, smaller city.”

Then, as if to say he really does know where he’s going, Jim adds this:

“They have their own city problems, too.”

— — —

I remember a story Jim told years ago when we were sitting over a beer in the River Heights dressing room.

It was about the time Elmer “Moose” Vasko, the big Chicago defenceman, pasted him into the boards so hard that when Jim looked up, his face was imprinted on the front of Vasko’s Black Hawks sweater. I remember laughing at the joke. But in a way, now I know the rest of his story. It’s not quite as funny.

Because I know that humour is one of the masks the old Lone Ranger wears. The one that helps cover the pain on his and so many other First Nations faces. Those same kind and gentle faces that frighten so many Winnipeggers.

gordon.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca