The true value of valour doesn’t have a price

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/11/2011 (5135 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Ernest Hemingway was working as a reporter for the Toronto Star just four years after the end of the First World War when he struck upon an offbeat idea for a story.

He would visit the city’s second-hand stores and pawnshops in search of the market price of valour.

In one window in his journey along Adelaide and Queen streets, he spotted a sign that looked as if it might offer the answer.

“We Buy and Sell Everything.”

“What’ll you give me for an MC?” Hemingway asked the female proprietor.

“What’s that?” she responded.

“It’s a medal,” Hemingway explained. “It’s a silver cross.”

“Real silver? If it’s real silver maybe I’ll make you a nice offer,” she said, smiling now.

“Say,” she said, her mood abruptly shifting, “it ain’t one of them war medals, is it?”

“Sort of,” Hemingway said.

“Don’t bother with it, then,” the woman advised. “Them things are no good.”

And so it went.

And, so it goes in a different, more personal way, nearly 90 years later.

As evidenced when my office phone rang last month.

A former Winnipegger named Donna Wallace was calling long distance from Gibsons, B.C., looking for another answer about another Military Cross.

A decade ago, her aunt, Eleanor Strain, died in Winnipeg and willed her the MC her first husband, Jack McNeill Galbraith, had been presented for an act of Second World War bravery that reads like a scene out of a Hollywood war epic.

On a moonless Italian winter night in 1943 — at the outset of an epic battle where more than 1,300 Canadians would die — the young Winnipeg officer and two soldiers under his command lugged telephone cable for three kilometres across a minefield to lay a vital communications line in the battle of Ortona. And, all the while under constant shelling. On the way back, Capt. Galbraith and the others would come across the body of a fellow soldier who stepped on a mine.

But Galbraith’s luck wouldn’t last.

Shortly after, he was sent back to Canada to receive his medal, having also received a diagnosis of cancer.

He died in Deer Lodge Veterans Hospital in 1947 and was buried in Brookside Cemetery.

Three years later, his widow, Eleanor, married Galbraith’s best friend, Robert Strain. But Eleanor kept the medal, and a scrapbook on her first husband’s gallantry, until she died a widow in 2001 in Winnipeg.

Which is how Donna Wallace came to have the medal and the scrapbook.

But a decade later, as Remembrance Day approached, Donna began to feel it was the Galbraith side of the family that really should have the medal.

If they wanted it.

And if she could find them.

Which is how she came to call me and later send a hand-written letter with a photo of the medal and some clippings from the scrapbook.

“We were wondering if you could write a small article asking if anyone in his family would like to have them, would they get in touch with you at the Free Press?”

Donna suspects there are still relatives here in Winnipeg.

And I suspect that, unlike the pawnshop and second-hand store owners from the Toronto of Hemingway’s day, Jack Galbraith’s family would be proud to have a symbol of his heroism in their possession.

I say that, in part, because of something else someone sent me last month.

George Sinclair is no relation to me, but he is to Doug Sinclair. It was the death of Doug’s uncle, George, that uncovered another family treasure, this one dating back to the First World War and a trunk in the basement.

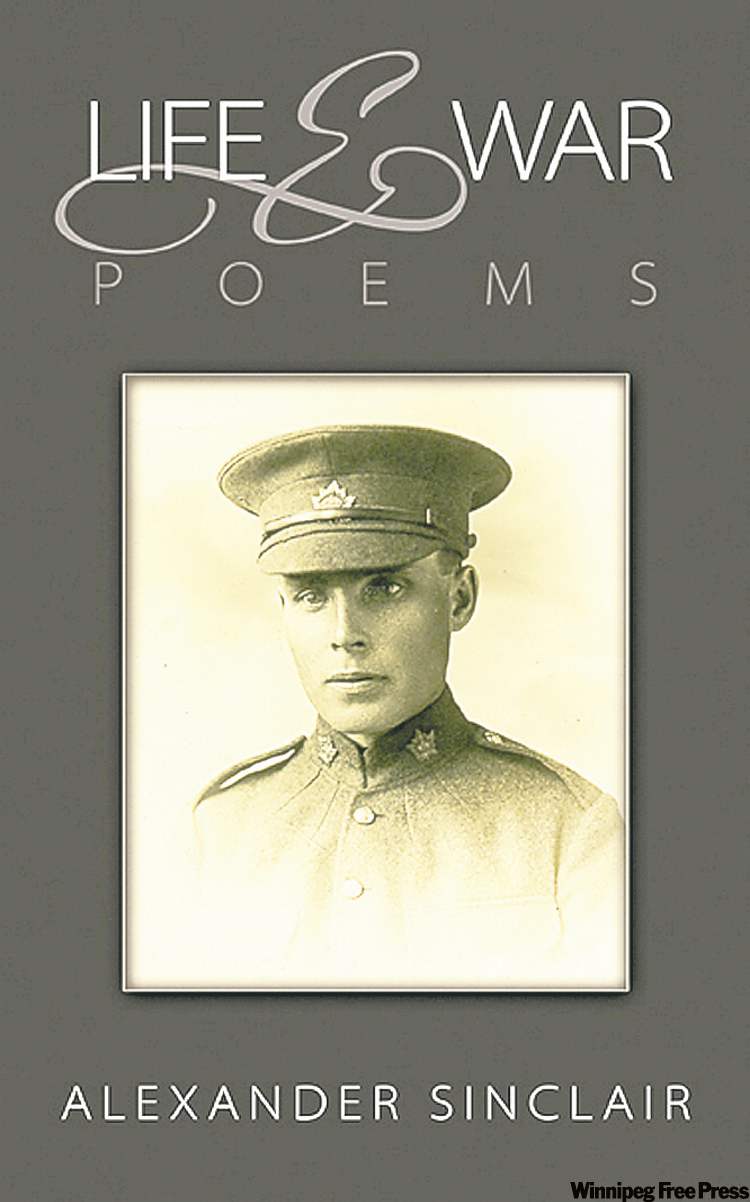

At the front, George’s father, Alexander Sinclair, was an ammunition driver at Passchendaele and Vimy.

But later, he would express what he saw in poetry he would later transcribe into a leather-bound ledger-style book.

A book whose contents so impressed Doug Sinclair he and his artist/illustrator friend, Garth Palanuk, have put 40 of the poems in a self-published book, complete with historical footnotes.

I don’t know if anyone else will find value in Life War & Poems, but obviously Alexander Sinclair’s nephew does.

Just as Jack Galbraith’s niece did with his MC and scrapbook.

Hemingway, it would seem, was simply asking the wrong people and the wrong question.

It’s family that best knows the true value of valour.

And the true cost of war.

gordon.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca