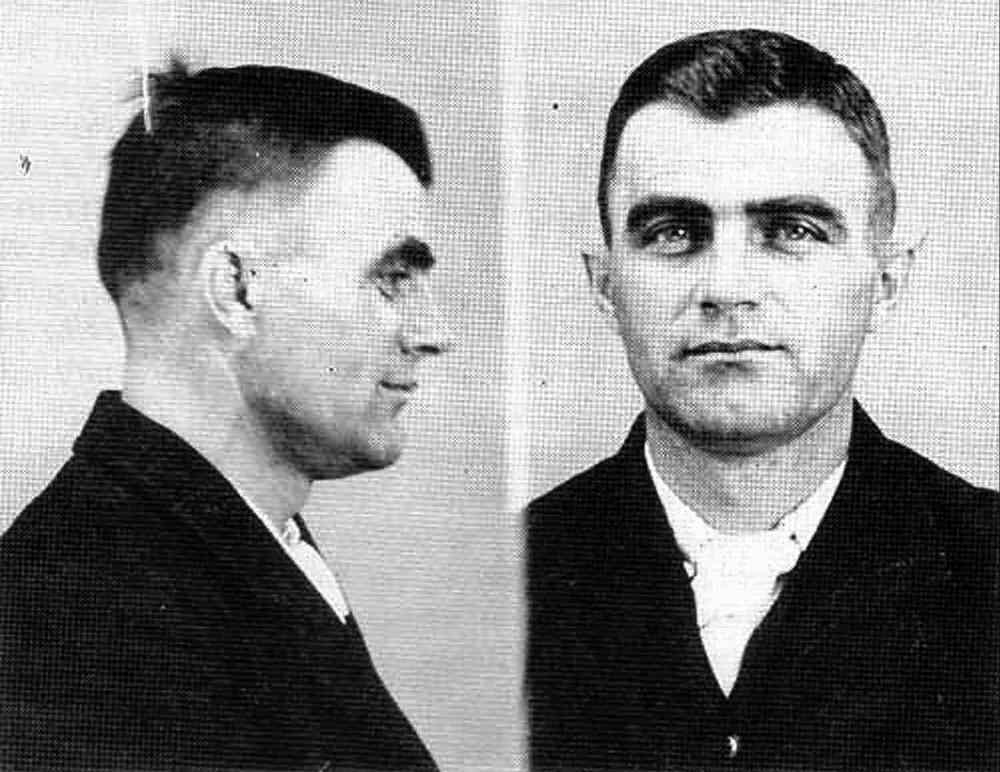

Manitoba’s ‘bloody’ desperado

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/01/2014 (4446 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

According to local legend, he was as charming as he was ruthless. The Free Press rightly called him a “notorious desperado.” One hundred years ago, “Bloody” Jack Krafchenko captured the imagination of Winnipeggers young and old in a crime of murder and robbery and a sensational escape from the city’s police station on Jan. 10, 1914 that ensnared a rising young lawyer and a police constable. The two had been lured into aiding Krafchenko with promises of a big payoff.

The saga of “Bloody” Jack is recounted in the pages of the Free Press, by Ontario author Edward Butts in his 2008 book Running With Dillinger and by local writer Martin Zeilig in a 1998 Manitoba History article.

Of Ukrainian heritage, Krafchenko was born in Romania in 1881 and immigrated to Manitoba as a young boy. He settled in Plum Coulee, 118 kilometres south of Winnipeg, close to Winkler and Morden. His father was the town’s blacksmith.

By all accounts, young Jack was clever and could speak several languages. But he also had a nasty temper and could not stay out of trouble. By the time he was 15, he had been caught stealing, more than once. At some point, he left Canada and may have gone to Australia where, so the story goes, he learned the art of boxing. He returned to Manitoba in 1902 and was soon arrested in Saskatchewan for passing fraudulent cheques, a crime for which he received a sentence of 18 months in the penitentiary in Prince Albert.

Within a short time, he added to his legend by easily escaping (after having been assigned work outside the prison) and then began his criminal career as a bank robber in earnest. He started with banks back in Plum Coulee and Winkler, before moving on to New York and then England, Germany and Italy.

He wound up in Russia in 1905. There, he married a woman named Fanica and they had a son. A year later, he brought his family back with him to Plum Coulee. He got a job as a blacksmith, though he returned to his old ways when he robbed a bank in a nearby town. For that crime, he got a three-year sentence at Stony Mountain Penitentiary.

Released from prison, he moved with his family to northern Ontario and worked in the railway shops. In 1913, he was back in Winnipeg drinking and gambling. Ironically, then-police chief Donald McPherson briefly hired Krafchenko as an informer to help the force nab a group of thieves. Krafchenko took the city’s money, yet he did not supply the chief with any reliable information.

For a bright crook, Krafchenko’s next heist was downright foolish. As Butts has noted, the population of Plum Coulee in 1913 was approximately 150, “and they all knew Jack Krafchenko.” Nevertheless in late November, along with two accomplices, he targeted the town’s Bank of Montreal. Bad winter weather prevented the men from robbing the bank on the day they had intended and his partners returned to Winnipeg

Krafchenko waited a few more days and carried out the robbery by himself. Disguised with a fake beard, he held up Henry Medley Arnold, the bank manager, at gunpoint and took $4,200 (with about the equivalent purchasing power today of $98,000).

As Krafchenko fled to a waiting car — the driver was William Dyck, a resident of Plum Coulee, who he had allegedly threatened — Arnold chased after him with a revolver the manager kept in the bank. Krafchenko shot Arnold dead. He then ordered Dyck to drive him out of town. After travelling 40 kilometres, Krafchenko had Dyck stop the car and he fled on foot.

Questioned by the authorities, Dyck told his version of the crime. Other witnesses in Plum Coulee had also seen the shooting.

Again, Krafchenko, either brazen or stupid, made his way to Winnipeg where he posed as a doctor at a boarding house on William Avenue and then as a St. John’s College professor at another boarding house on College Avenue. He was on the run for about a week.

He bragged to some of his cronies about the money he had stolen and hatched a plan to leave the city dressed as a woman. More than likely, one of crooked characters he encountered, Bert Bell, told the police where Krafchenko was hiding. He was also seen by William Stephenson, the future spy who in 1913, as a teenager living in Winnipeg, worked as a telegram messenger. Stephenson reported the sighting to the police.

On the morning of Dec. 10, the police swarmed the College Avenue boarding house and captured Krafchenko, who had been sleeping. Detectives found a loaded gun under his pillow. They located a roll of about $800 of the robbery money hidden near the house and recovered another $740 in the southwest part of the city, probably cash Krafchenko had given to Bell to help him flee.

“The arrest was made as the result of clever police strategy,” the Free Press reported the following day, “and entailed much surveillance of private dwellings and the use of ‘stool pigeons.’ “

By early January, Krafchenko had been charged with murder and robbery and was incarcerated at the jail in the main Winnipeg Police Station, then on Rupert Avenue. For some reason, the police locked him in a guarded room, rather than a cell.

Unknown to the police, Krafchenko was plotting his escape. His lawyer, Percy Hagel, the 30-year-old son of N.F. Hagel, a highly respected Winnipeg criminal lawyer, and Const. Robert Reid, one of his guards, had been wooed by Krafchenko’s stories of possessing a treasure of loot. Together with two other men Hagel had recruited, John Westlake and John Buxton, they conspired with Krafchenko to engineer his escape by providing him with a gun and a clothesline rope. Reid secretly gave him the items on Jan. 8.

Two nights later, at 2:30 a.m., Krafchenko made his move. He used the gun on his guards. Reid, who played his part well, and another constable were locked in a closet. Krafchenko took Reid’s keys to enter another nearby room, crawled out the window and with the rope tried to climb down to the ground, a drop of about 10 metres.

As Krafchenko later testified, as he was descending, the rope broke and he fell hard on the icy sidewalk below, badly injuring himself. He claimed while hobbling down William Avenue, an unsuspecting driver (or it might have been Hagel) stopped to offer him a ride to Westlake’s apartment on Toronto Street.

It took another week for the police to recapture Krafchenko. In the interim, as the largest man-hunt in Winnipeg history was proceeding, Reid, under intensive questioning, revealed all about the scheme.

Reid was arrested and was sentenced to seven years at Stony Mountain, where he soon died in an accident. Likewise, John Westlake received a two-year sentence and Percy Hagel, three years. Hagel was disbarred, though after he was released was reinstated by the Manitoba Bar and practised law in Winnipeg until he died in 1944. The other participant in this intrigue, John Buxton, who had testified for the Crown, was given immunity and a new life in the U.S.

“Bloody” Jack Krafchenko stood trial in Morden, was found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang. The execution took place at Winnipeg’s Vaughan Street jail on July 9, 1914. A crowd of 2,000 people stood outside on the street in awe of Krafchenko’s criminal celebrity, but undoubtedly relieved that justice by 1914 standards had been done.

Now & Then is a column in which historian Allan Levine puts the events of today in a historical context.