Stories told, healing awaits: Release of Truth and Reconciliation report another step in journey

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/05/2015 (3824 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s hard to tell exactly when Canada began in earnest to deal with the ugly, violent legacy of the Indian residential school experience, but there is a good argument the turning point came nearly 25 years ago at a Winnipeg native youth conference.

It was October 1990 and Phil Fontaine, then head of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, admitted he had been sexually abused during his decade in the residential school system.

Fontaine’s address to the youth took place in the aftermath of a series of emotional meetings with church officials to discuss help for the survivors of residential schools in Manitoba. Perhaps as a result of confronting officials from churches responsible for so much of the abuse, Fontaine was unusually frank in his comments. “Of course (I was abused),” Fontaine told the youth conference. “We all were.”

With those words, Fontaine blew the lid off decades of silence and shame. It wasn’t as if there had been no concerns expressed about the impact of residential schools; the United, Presbyterian and Anglican churches apologized about their roles in operating the schools several years earlier. However, up until this seminal moment, Canadians had lived within a cocoon of profound misunderstanding about the schools because many of the victims had never come forward to explain what really happened. Most Canadians believed that although the policy was wrong, the intent had been honourable. The shocking admission from Fontaine, a nationally recognized aboriginal leader, showed there was untold evil that had yet to be exposed.

Within days of his comments, several churches had announced committees to further study their own role in residential school abuse. Opposition politicians called on the federal government to launch a public inquiry. More importantly, thousands of aboriginal Canadians who had never spoken of their abuse began to come forward.

That flood of personal stories, and thousands of accompanying civil claims, created momentum that allowed Fontaine, who went on to lead the Assembly of First Nations, to open up new lines of negotiation with the churches and government over a more comprehensive response to the residential schools legacy. It was not an easy road for Fontaine; he was criticized both by aboriginals and non-aboriginals for dancing with the devils that wrought the residential school system.

And yet, in large part thanks to his continued leadership, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) was reached in 2006. In addition to nearly $2 billion in compensation, the settlement also called for the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the first serious investigation of the residential schools experience. The TRC, which began its work in 2009, will release its first report next week in Ottawa.

Fontaine, now 70, said in an interview that although some will see the past 25 years as an unconscionable delay in revealing the truth about residential schools, there is a strong argument to be made that it was the right amount of time to get to this historic moment. “We never thought it would be an overnight success,” Fontaine said. “We anticipated that it would take some time. I think it’s good that it’s taken this long, because it affords us an opportunity to do everything that needed to be done.”

The TRC’s work was, in a word, exhaustive. The TRC held seven national events in cities across Canada to meet directly with survivors and their families. To date, the TRC has collected more than 7,000 statements and more than 5,000 legal and historical documents. Together, they form the first truly national archive on Canada’s residential school system.

The report to be released next week — an executive summary of findings and recommendations that will be followed by a longer report in the fall — is expected to fundamentally alter Canadians’ view of the residential school system.

“The (TRC) report will give Canadians a much clearer picture of the residential school experience,” Fontaine said. “It will be informative, it will be educational and it will, in my view… shock Canadians. But this is a story that has to be told so that Canadians will know this is their history. It’s not just a story about survivors.”

Among those details expected to shock is the estimate of the number of children who died in the system. To date, authorities believed about 4,000 children died at residential schools. That number is expected to rise significantly, along with the specific stories of atrocities, some of which bear a disturbing resemblance to events associated with confirmed genocides.

Some of these stories have been floating around for years, but others will be new to the national debate. In addition to confirming the extent of physical and sexual abuse, the stories are expected to touch on a number of areas, including: forced sterilization of aboriginal women; unreported and undocumented deaths of children buried in unmarked graves; forced child labour; inhuman living conditions and deliberate neglect that led to deadly disease outbreaks.

It is the venting of these stories, really for the first time in our history, that many believe will recast our perspective on aboriginal people and the challenges they face today. In particular, that the forced and systematic deconstruction of a culture has affected, and continues to affect, the day-to-day lives of aboriginal people.

“At every single event, we heard allegations of sexual abuse,” said Ry Moran, director of the National Research Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba, where the TRC archive will be kept. “And for many of the survivors, we were the first people to ever hear those allegations. The thing that many Canadians need to understand is that you don’t really get over childhood sexual trauma. It creates a lifelong need for healing and understanding. And right now, the amount of healing we’re asking aboriginal people to do now is extraordinary.”

The IRSSA is now nearly 10 years old and much has happened since it was reached and approved. Prime Minister Stephen Harper has officially apologized for the residential schools policy in the House of Commons. And more than $1.6 billion in compensation has been paid out to survivors. With all that in the rear-view mirror, many will be wondering what the TRC will recommend as future action?

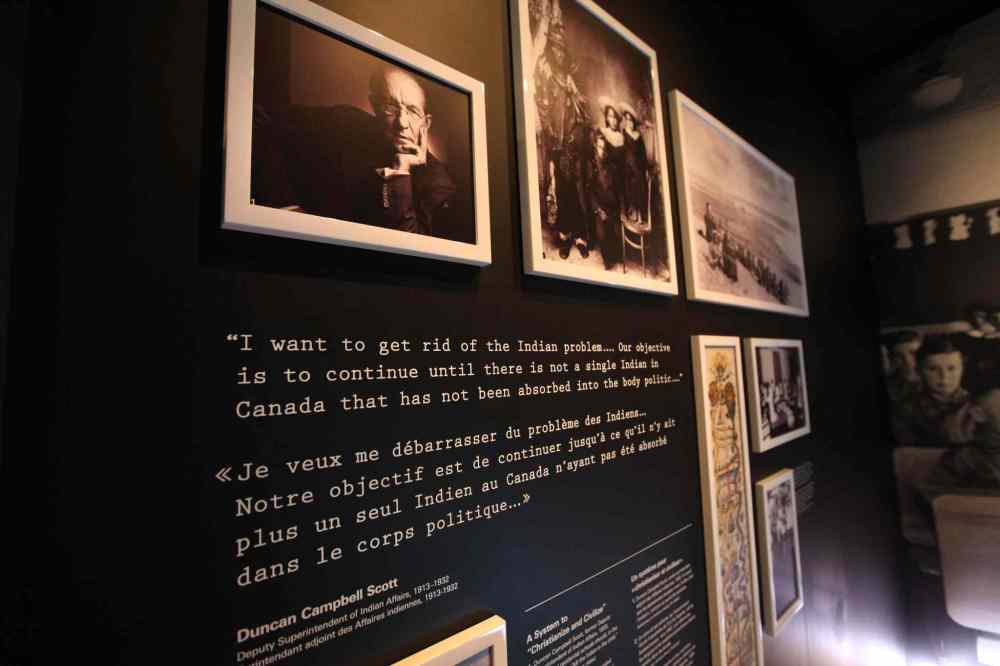

Somehow, the TRC will have to deal with the issue of potential criminal actions. The commission is expressly forbidden from making findings of guilt or liability. However, Justice Murray Sinclair of the Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench, the TRC chairman, has already piqued the interest of many by declaring that the residential school system was an act of genocide.

Typically, a court or other legal body is needed to attach the word to an event or period of history. In those countries where a genocide has been confirmed, there are usually efforts made to prosecute those responsible. It is unclear now whether the TRC will even recommend further investigation or prosecution. That will not stop many observers from moving closer to the use of the word genocide in any reference to the residential schools system.

“When we talk about exposing this experience, we can’t pussyfoot around these issues,” said Fontaine. “But academics and politicians have talked about this experience as a genocide. Justice Sinclair has made the point that he thinks it is a genocide. People will argue Canada is not like Nazi Germany, and that’s absolutely true. But we have our own warts and we’re going to need a fair and honest debate about those.”

Of all possible impacts the TRC report could have, none may be as important as changing the way Canadians learn about aboriginal people. Moran said it is widely expected the TRC will recommend its report and archives be used to redraft curricula across Canada.

Right now, Moran said he is in discussion with educators across the country about how to include the research centre’s archives in the development of new history and social studies curricula. The research centre itself will be open to both the public and to researchers looking to further their understanding of the impact of residential schools.

“In terms of understanding the harms that were done, Canadians on the whole have a profound blind spot,” said Moran. “The facts have been, to this point, really suppressed. It will take some time before all this is fully understood.”

That realization — the nation is in many ways just starting to learn about the impacts of residential schools — speaks to another reality: that Canada is also just beginning the process of developing programs and mechanisms for restoring aboriginal culture and breaking the legacy of residential schools.

Although there have been attempts at mental and physical therapy, and financial compensation, there are many who believe comprehensive efforts to heal the victims and their families can only begin with a greater understanding of what happened.

On that note, Fontaine believes the last 25 years are only the beginning of the process.

“It’s one more story, one more process, one more report. This is not the final story.”

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Dan Lett is a columnist for the Free Press, providing opinion and commentary on politics in Winnipeg and beyond. Born and raised in Toronto, Dan joined the Free Press in 1986. Read more about Dan.

Dan’s columns are built on facts and reactions, but offer his personal views through arguments and analysis. The Free Press’ editing team reviews Dan’s columns before they are posted online or published in print — part of the our tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, May 30, 2015 1:44 PM CDT: Corrects misspelling of Ry Moran.