Christmas on the Prairies

Family, friends and frozen toes — things weren’t so different 135 years ago

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/12/2015 (3722 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Christmas is coming. So are the Boxing Day sales extravaganzas, where you might be trampled trying to purchase a flat-screen TV for $200.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens has also arrived, although with just a little more fanfare than would be afforded the Second Coming.

Your in-laws, will soon be showing up for the holidays, too, including the uncle who thinks Donald Drumpf “tells it like it is.”

The toys under the tree — for the rosy-cheeked children, at least — will be technologically baffling to the generation that considered Pong and Tetris the razor’s edge of the video-game industry.

Perhaps you will FaceTime with Aunt Betty, who is on holidays in Hawaii. At the very least you will spend a majority of Christmas Day staring at your smartphone to see how many Twitter followers favourited the picture you posted of your cat wearing antlers.

By nightfall, you will be filled with one part turkey, two parts stuffing and one part Nanaimo bars; half awake watching Jimmy Stewart slap around Uncle Billy for losing the Building and Loan’s money for the 82nd time.

Christmas in 2015 can be stressful. It can be special and joyous, too.

But did you ever long for a simpler, less-commercial holidays? You know, like when grandpa talks about the time he got a block of firewood for a gift that he whittled into a smaller block of firewood? Or how the only treat on Christmas Eve was icicles dipped in sugar?

Well, just imagine when buffalo still roamed the prairies and Manitoba was just a teenager. There were no last-minute flights home or PlayStation 4s. No instant stuffing or phones that gave directions or blockbuster movie sequels.

In an effort to get a taste of Christmases past, we dug around in the Hudson Bay Company archives to get a few glimpses of what the holidays were like for early pioneers. You know, just to see what kind of gifts they were ordering off eBay and stuff.

The Selkirk Settlers had arrived during the previous decade — the first Europeans to homestead in Manitoba. Hudson Bay Company clerk Francis Heron noted in his diary that because Christmas that year fell on a Sunday, “the people have put off the amusements usual in this community on this holy day.” They just attended church “as customary.”

On Monday, Dec. 26, however, the settlers got jiggy with it. In the Fort Garry Journal, Heron wrote: “The men of the establishments were given the few luxuries, and liquors, they have been accustomed to receive at this season, and helped the day in conviviality and amusement. Then have been allowed a respite from labour of 10 days, in consideration of their past good conduit and industry. The freeman and Indians continue to bring in a considerable quantity of Muskrats to trade — many of them come from beyond the boundary lines to trade with us, in consequence of the good encouragement given for peltries at this place. Indeed the high prices given for furs induces many people to hunt, who would otherwise keep their time in idlement.”

So business was good for the settlers, traders and trappers.

But Heron’s entry on Jan. 2, 1826, was more troubling, recording that several members of the nearby First Nations were gathering at the settlement “in state of extreme starvation… in the hope of obtaining a subsistence from amongst the colonists, their own resources having failed them. The daily accounts from the plains confirm those already received of the great scarcity and remoteness of buffalo. The state of starvation to which the freemen and Indians are thereby reduced exceeds in extant of anything of the kind ever, experienced at any former period in this quarter. These unfortunate people have already been reduced to the necessity of eating their horses, dogs and such parts of their garments that were of leather.”

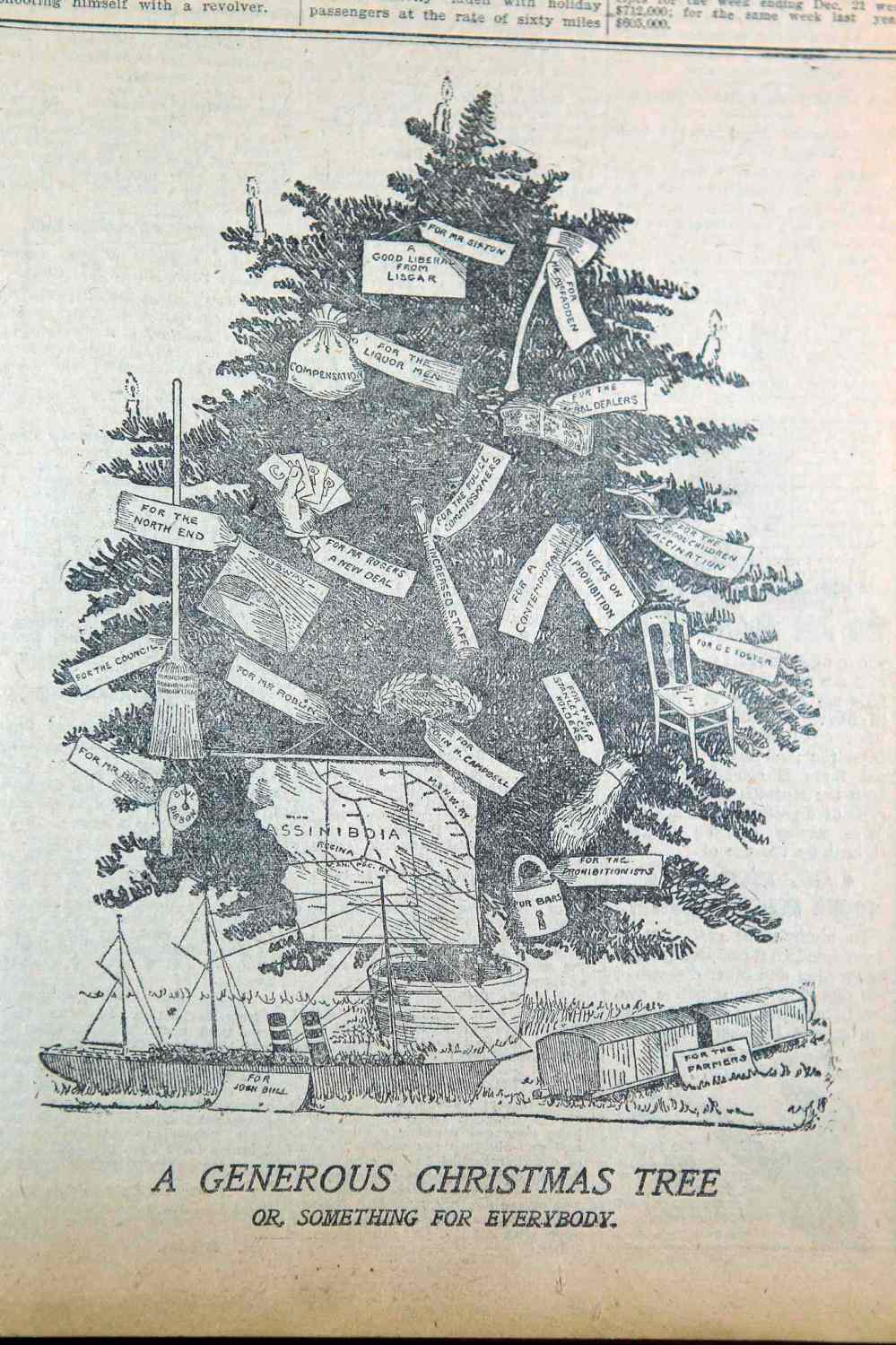

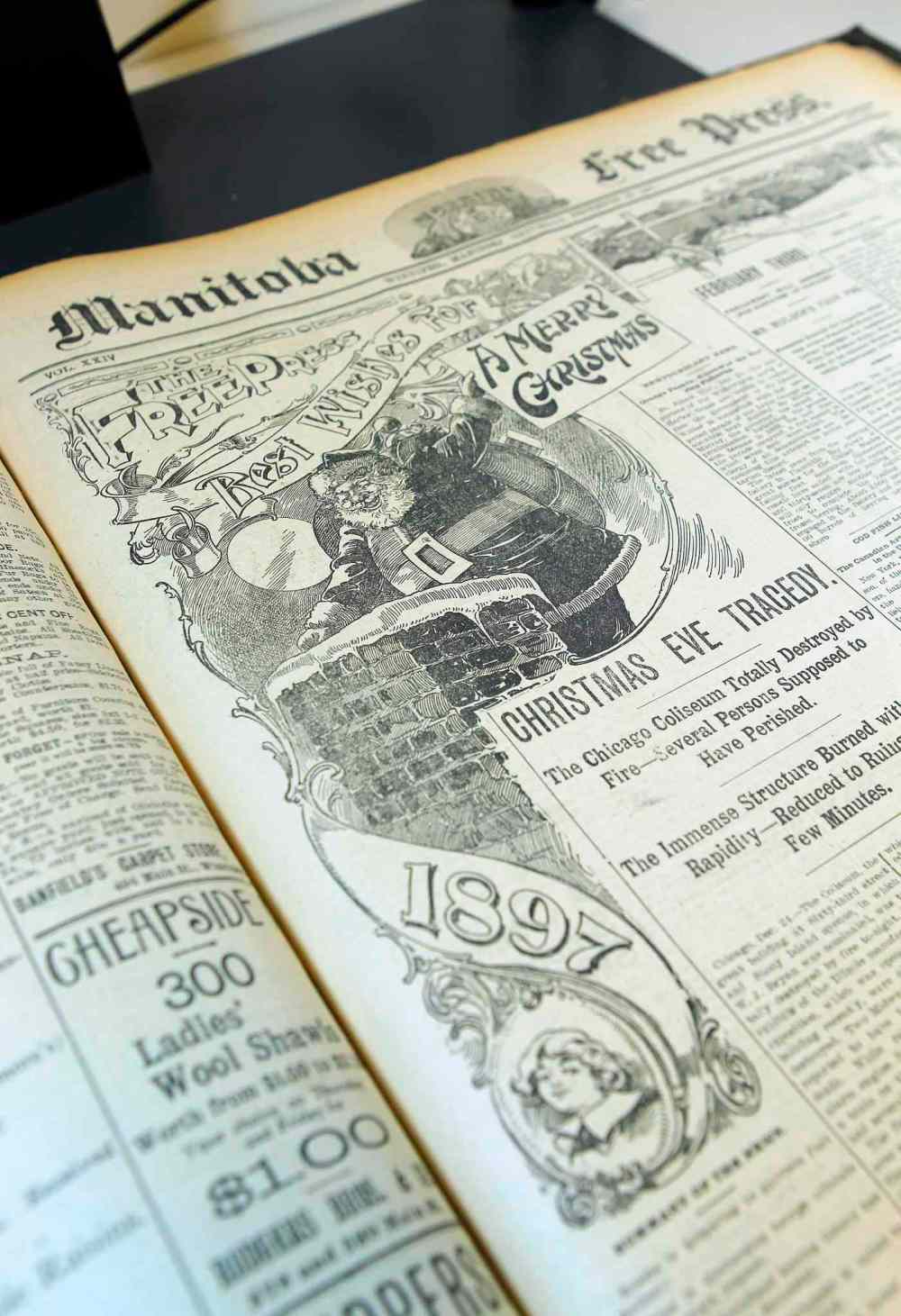

Manitoba Free Press, Dec. 25, 1882:

“City post office handled exactly 125 bags of Xmas mail — the largest quantity ever handled in Winnipeg in one day.”

“There was no session of the police court, but all drunks, with the exception of two old offenders, were given their liberty.”

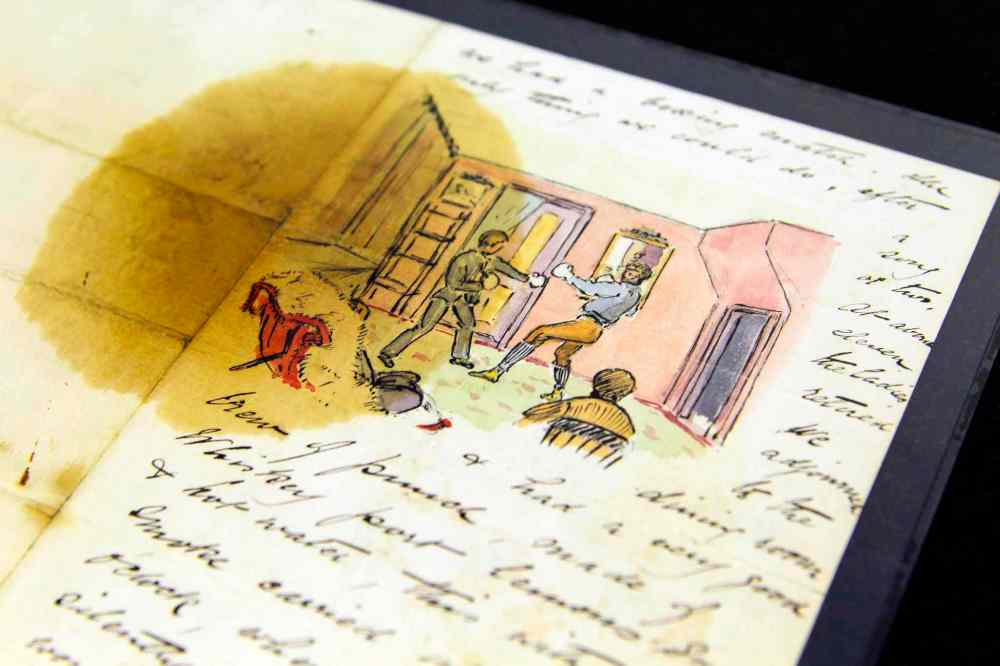

Fredrick Phillipp emigrated to Canada from Padstow, England, in 1880, searching for an “outdoor life.” He settled near Riding Mountain, where he built a cattle ranch. Phillipp would often send illustrated letters to family members in England.

In this letter, dated January 1888, Phillipp describes a Christmas visit from some friends and their family.

The best part of the missive is the hand-drawn illustrations. The second-best part: how they entertained themselves by drinking and boxing into the wee hours.

In part, the letter reads: “We are here waiting the arrival of our guests… the weather was pretty awful, blowing very hard and 12 below zero. One of the poor little things (a girl guest) feet was frozen and had to be thawed out with cold water, we unfroze the old boys (father’s) nose with a glass of Whiskey. We had quite a successful dinner and drank to health of absent friends. We were to have had a play Cox and Box after dinner but a young fellow who was to have taken the part of Cox never turned up so all my hours of standing were clean thrown away.”

(Note: Cox and Box is a one-act comic opera written by Arthur Sullivan in 1866.)

The festivities on Christmas evening, however, became a tad more physical as the men squared off for some playful fisticuffs in the dining room after the ladies retired.

“The only thing we could do, after a song or two,” Phillipp wrote (and drew). “At about 11 the ladies retired. We adjourned to the dining room and had a very good brew of punch, make of Whiskey port lemons sugar and hot water, this with tobacco smoke carried us to two o’clock, when each stalked silently to his own chamber wondering whether life was worth living but everybody was at breakfast the next morning at 9:30 and strangely nobody was at all unwell.”

Now THAT’S a Boxing Day.

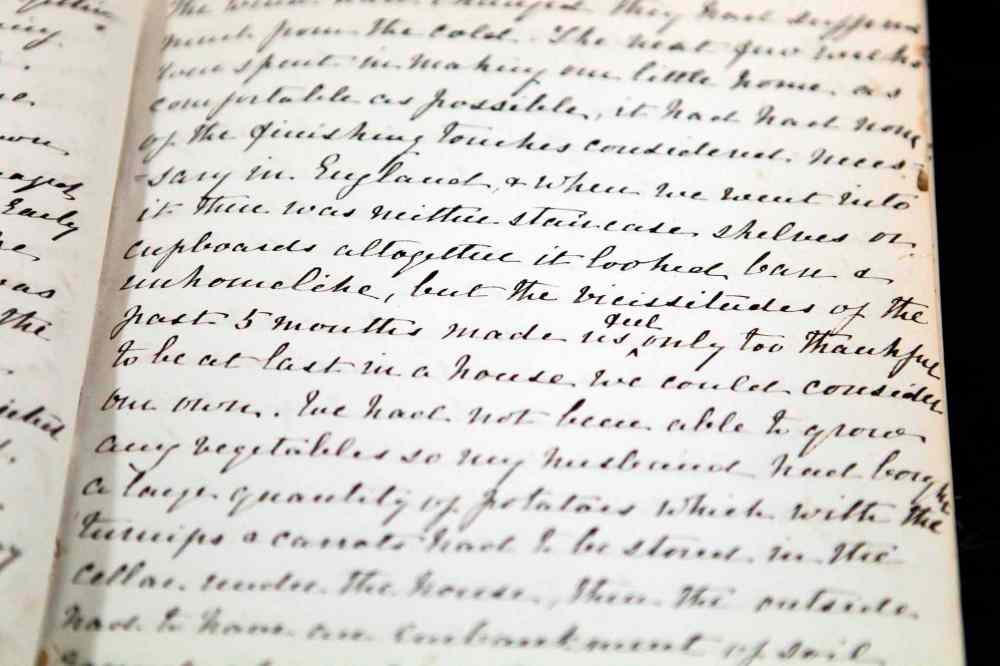

Emma Louisa Averil left Liverpool, England, with her young family on April 1, 1880, eventually arriving by oxen-drawn wagon at the hamlet of Grand Valley, located about five kilometres east of what is now Brandon. But in the winter of 1882, the family was huddled in a 20-by-16-foot homestead, preparing for Christmas. And shivering.

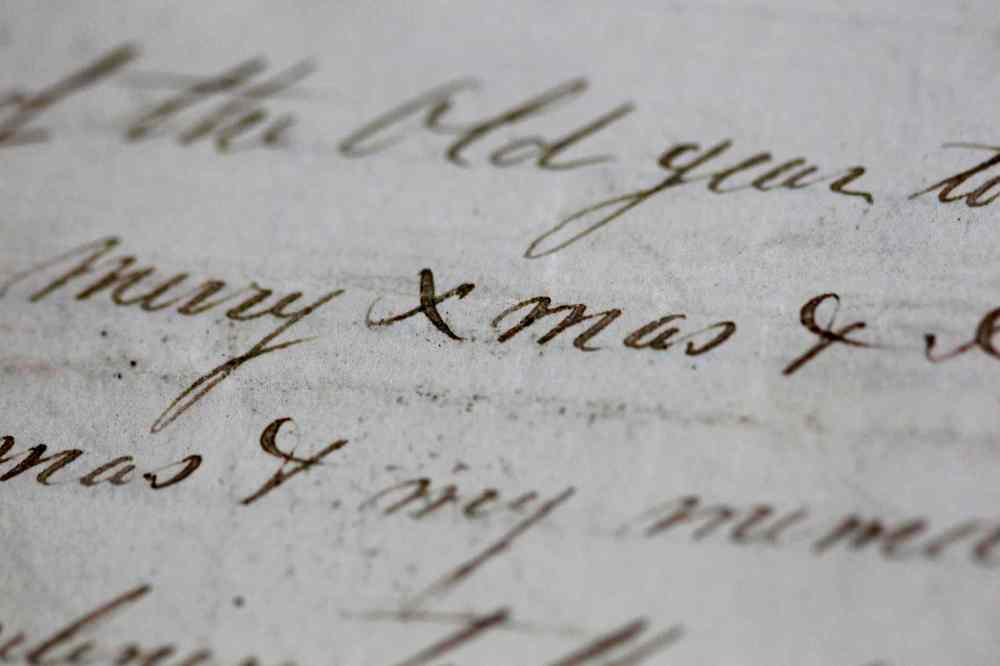

“Xmas morning was cold enough to make anyone contemplating a visit prepare against a gamut of frostbite,” Averil wrote, noting most of the family slept on mattresses that were just bags filled with hay and flour.

Averil said noses of the pioneers were “not infrequently frozen” and that her husband wore three pairs of knitted socks under moccasins and had mittens of thick leather lined with lamb’s wool.

“I can imagine any Englishman laughing at that the idea of using his hands so incased, yet people chop and shoot with them,” she explained.

Averil added: “The severity of the frost must be felt to be understood, it is no uncommon thing to find in the morning our breath frozen in small icicles on the Buffalo robe under which we slept and the same on my husband’s moustache and beard, yet this was a mild winter compared with the one of 1879 and though my husband would often come in and declare this country never was intended for Englishmen, he more frequently said, ‘Is this not a splendid climate, could anything be better?’ ”

Manitoba Free Press, Dec. 23, 1887:

“About 100 railroaders came in from the line this morning to spend their Christmas holidays. A number had their ears and toes frozen while making the trip on flat cars.”

The holiday season was also a time of reflection, in particular during the embryonic and often violent stages of the province’s political evolution. On Dec. 24, 1872, the Manitoban carried a front-page editorial that harkened back to the election riots in the fall of that year. Those riots were embers of the Riel Rebellion, where Protestant Orangemen, many from Ontario, and other English-speaking residents attacked Métis and their supporters over a new law that prevented newcomers from voting until they had resided in the province for two years.

“Since last Christmas our own little province has not been without its trials and troubles,” the editorial stated. “For a time and on till the fall, things went on satisfactorily. A large number of immigrants came in. Preparations were being made below for a more extensive immigration, but towards the end of the year our little province passed through a severe ordeal; a band of felons, thinking that our people were dismembered and that they so hated each other that the word of annexation only required to be given to bring about a general disruption, invaded the province. But what was the result. It was found, notwithstanding all that had been said, the people were loyal to the core. Well, then let us act henceforth on this understanding. Let us join hand in hand in developing the resources of our province. Let us lay aside all our petty differences. And the best way in which we can do this is to act on the principle of the first Christmas, extending peace and good will to men.”

In the spring of 1888, Kate Johnson’s parents left their family farm in Denmark and arrived in Manitoba not long after the Riel Rebellion when, as she wrote, “Scarlet-coated Mounties continually patrolled the plains.”

The family established a 160-acre homestead in southeast Saskatchewan, near the Manitoba border. They had Bess, a large grey cow that broke the virgin prairie, along with Mack, a tall rangy ox.

There was also Dick, a huge roan bull, an animal Johnson described as “docile and gentle as a proverbial lamb.” In fact, the children would ride on Dick’s back to fetch water. “At their command,” Johnson wrote, “he would lower his head to the ground, allowing them to sit on his horns, thus mounting him from the front.”

In Cameos from Pioneer Life in Western Canada, Johnson recalls her mother making handmade decorations, including coloured paper “that served as receptacles for nuts, candy and raisins, as they dangled from the tree.”

Other decorations were made from magazine pages and tin foil from grandfather’s tobacco packs. The star atop the tree was made from a cut-out sheet of tin, and cookies with holes in them hung from the tree branches with bits of string.

On Christmas Eve, the children each received a present: “Games or toys for the boys, and dolls for the girls. Once, the dolls were accompanied by tiny wooden cradles, made by grandpa, and fitted out with sheets and pillows, the work of mother’s hands.”

Dinner consisted of cold roast pork, followed by cookies and coffee topped with thick yellow cream.

“During the evening, the big book of Bible stories that had been brought from the Old Country was taken down from the shelf, and father read aloud the familiar Christmas Story. Stille Nat (Silent Night) the favourite of everyone, was sung first.

“But I must not forget to mention the big jumping jack,” Johnson concluded, explaining sheets of cuts-out from Denmark would arrive every Christmas. The figures were cut out and glued to props to make them stand erect. One of those props was the breast bone of a recently consumed goose, which was dried and scraped clean. Arms and legs were attached by string. A tongue was fashioned out of soft wax.

“It became a living thing, that leaped wildly about the floor, causing the youngsters to shriek with delight,” Johnson wrote.

Manitoba Free Press, Dec. 25, 1899

“The Victoria Hockey Club has again challenged for the Stanley Cup.”

William Lothian was a young Scottish immigrant who arrived in Canada with his brother Jim in 1880, eventually settling in Pipestone Valley. He married childhood sweetheart Annie Milliken and raised four children.

But during his first Christmas holiday in Canada, Lothian — an amateur poet and briefly a reporter — found himself alone on New Year’s Eve in a sod hut. That night, he penned a letter to family to assuage his homesickness. The address was listed as OHBCFRMNWTNA (Old Hudson’s Bay Co. Fort, Riding Mountains, North West Territories, North America).

“The last days of a memorable year to us all,” Lothian wrote. “The days as a rule are sunny and clear, the air dry and bracing, better than wading in mush and slush as at home. But it’s awful cauld when there’s a wind blowing… Lord Dufferin tells the truth in forcible language in which Jim and I have been quoting 50 times a day. You will see it in pamphlets printed across the country: ‘The air, though cold, is sufficiently bracing and is the most potent incentive to physical exertion. A constitution nursed upon the oxygen of our bright atmosphere makes the possessor of it feel as if he could toss the pine trees in his glee.’ Certainly, when actively employed you do get a fine glow.”

Lothian boasted that, “For character and a daring recklessness spirit whose delight is to be surrounded by danger, this is the life.”

Finally, the young Scotsman offered this one last observation on his new home:

“Coming up from the country we got much free and contradictory advice. One would say on hearing we were going to Manitoba, ‘A splendid country, just the place for a young man.’ Another would say, ‘Oh, never go there… I was glad to get out; you’ll be eaten by mosquitoes in summer and be frozen to death in winter.’ If you divide the two accounts you are about right perhaps.

“Your affectionate son, William”

Curious. That last paragraph written by William Lothian on New Year’s Eve 135 years ago might have been written last week. Just a reminder that, for better or worse, history is witness that the past can be found alive and well in the present. The Christmas holidays are no different.

While some prosper, neighbours can be in great need. New immigrants are still adapting and thriving in a new land. Icicles are still forming on beards during the depths of winter. And there still is no consensus on the age-old debate pitting Splendid Country vs. Frozen to Death in Winter.

Lothian was right. It’s probably somewhere in the middle.

Merry Christmas, one and all.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.