Vinyl revival

Music fans seeking superior sound turning to records

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/01/2016 (3579 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

One of the biggest music-business stories in the last couple of years has been the surprise re-emergence of records.

While hardly a threat to digital downloading or even CD sales, vinyl sales have been on the upswing, increasing some 38 per cent in 2015 from the previous year. Even contemporary artists such as Taylor Swift and Alabama Shakes are having their latest efforts pressed on vinyl, showing vinyl’s domain extends beyond the mouldy oldies.

Nielsen Music, which tracks music sales in various formats, said 5.6 million vinyl records were sold in 2015, more than double the figure for 2010. And it’s not just baby boomers leading this resurgence: young people are discovering the joys of vinyl recordings.

For many of us who grew up with vinyl records — the 12-inch 33 1/3 r.p.m. long player album (LP) and the seven-inch 45 r.p.m. single — there is a special feeling that comes from listening to a record. For some listeners it’s partly nostalgia, but it’s also the depth and richness of the sound a decent-quality vinyl pressing offers.

Vinyl devotees insist there is warmth to the vinyl sound, compared with the more sterile and clinical digital sound of CDs or streaming. Digital sound places everything up front and is subjected to excessive compression and dynamic range reduction that allows for increasing audio levels. Known as “loudness wars,” the practice is criticized for sacrificing sound quality for volume. As Bob Dylan noted, “You listen to these modern records, they’re atrocious. There’s no definition of nothing, no vocal, no nothing, just like — static.”

Of course, new recordings pressed on vinyl are nonetheless recorded digitally as opposed to the old analogue tape method, so don’t be fooled into thinking your new Taylor Swift record will yield the sound quality of a ’70s-era Led Zeppelin album. However, you will feel some of the warmth that only comes with the vinyl experience.

“Digital sound is inferior,” says Guess Who and BTO veteran Randy Bachman.

“There’s no depth, definition or fidelity. It’s all up front, with no bottom end. Listen to a BTO record on vinyl. Compared to a CD or a download, there’s so much ‘bigness’ from the vinyl. Digital sounds like it’s coming from a tiny little speaker. It’s just a just a million ones and zeros. Yet sound quality isn’t important to the digital-downloading generation today because they’re listening to the music on iPods, earbuds or similar devices that flatten out the sound.”

On the plus side, CDs and downloaded or streamed music on iPods last a long time and don’t degrade with repeated playing, unlike vinyl. They are also more portable and easier to store and carry around.

For vinyl enthusiasts, there is the tactile sensation of holding the cardboard album sleeve, removing the vinyl record, placing it on a turntable, lifting the needle to connect with the groove and hearing the sound when metal stylus meets vinyl, that initial noise as the stylus makes contact and follows the groove to the first notes of the track.

“My preference is vinyl,” says local musician Jeff McIntosh, “because I enjoy the experience of vinyl. I like cleaning the needle with my little brush and bottle of solution, then zapping the LP with my anti-static gun, prepping the LP prior to playing. I like the mechanics of the turntable as well. The whole turntable deal makes me feel like I’m part of the process in the overall listening experience. With a CD, you just shove it the hole and it’s a done deal. More than that, there’s a dimension or realism to the music that vinyl reproduces that CDs don’t. Vinyl has the ability to recreate the illusion of real people playing real instruments in a real venue. CDs don’t do that. Vinyl versus CD is like karaoke versus a live band.”

“I look at different sources for delivery of music in the same way I look at different ways to dine,” says ex-Winnipegger Richard Bowden, director of sales for Toronto hi-fi store Bay Bloor Radio.

“Think of streaming as fast food. You may use it as background soundtrack, not too much attention to details. Think of a CD as a step up, perhaps bistro food; still not serious attention. Think of vinyl as fine dining. You take the time to look at the cover, read the liner notes (menu), and take time to prepare, cleaning and setting up the system. The most important part is taking the time to sit back and actually enjoy the music.”

Evidence the fine-dining experience is on the rise is found in recent sales figures.

“We sold about 400 turntables in the November-December time frame,” says Bowden, “and approximately 50 CD players.”

That tangible experience also comes with the album sleeve itself, the artwork, track list, liner notes and recording details, if included. Vinyl enthusiasts often point to sleeve or liner notes as being a key factor in their appreciation of the vinyl album.

‘Vinyl versus CD is like karaoke versus a live band’

— musician Jeff McIntosh

“Why do I prefer vinyl albums? Three words: readable liner notes. When I was a kid, I would go downtown with no money and go to Opus 69 or Autumn Stone. While listening to whatever was playing or going into listening rooms, I would read liner notes incessantly,” says musician Robert Zaporzan.

Winnipeg guitarist Steve Chisholm says, “Listening to vinyl goes beyond the audio experience, much like opening a book goes beyond reading words on a page.”

“It’s that tactile aspect. Vinyl covers usually included photos, lyrics and background information. New records also had their own version of that ‘new car smell’ when you opened the cellophane.”

Personally, I scrutinized album liner notes like an archaeologist uncovering ancient scriptures, memorizing details that were relevant to me in fully appreciating the recording I held in my hands. That information was shared and discussed with other like-minded music fans.

What teacher and musician Jay Willman loved about vinyl albums was “the experience of going to Autumn Stone and other stores, then hopping on the Selkirk-Keewatin bus and going to a friend’s house with my badges of honour, my LPs under my arm for all to see, and people striking up conversations about those bands. ‘Hey man, the Guess Who, cool.’ “

Audio expert and founder of Banquox Sound Henry Kreindler, says, “Listening to music 40 or 50 years ago was much more than just wasting time.”

“It was a gathering of friends exchanging opinions and ideas about the art, the music and the album cover.”

Nowadays, music is more likely to a singular experience than a collective one.

“Vinyl seems more authentic,” says teacher and musician Bill Tibbs. “It brings back the excitement I felt when a new album came out.”

Bachman says young people now “see music as far more disposable.”

“It’s instant gratification by downloading an individual track. Easy come, easy go. Two days later, they’ve moved on. When I used to buy an album or a single, I’d listen to it for days on end and would come back to it even after I’d bought other records. Before I bought it, I might have stared at it at the record shop and imagined what sounds were inside it.”

Album cover art was, indeed, an art form unto itself, whether photographic or painted. I bought many an album simply because of an intriguing cover. Albums such as King Crimson’s debut with that gaping mouth, Cream’s Disreali Gears, with its psychedelic collage, the haunting-looking painting on Derek and the Dominoes’ Layla or the Moody Blues’ gatefold album paintings, just to name a few — that’s art.

Look at early Rolling Stones album covers. The black-and-white photographs of the band members — all dark, sullen, greasy hair and pimples — was an unmistakable representation of the raw, gritty music inside.

“I love the album-cover art,” says vinyl collector Sharon Race. “It’s so comforting to take out a record and put it on the record player and enjoy the album jacket while it’s playing.”

Consider the Beatles’ 1967 magnum opus Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Beyond the time spent writing and recording the tracks, the band took the cover art seriously enough to commission artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth to create one of the most striking pieces of album art of its time. And including the lyrics on the back was a first. The album cover won a Grammy award that year.

How important is that art to the album itself? Indispensable. Download or stream the album tracks alone and you miss that art completely. Minus the artwork, they have no sense of a whole concept or theme.

Similarly, consider the sequencing of the album tracks. They are not placed in random order, nor in the order in which they were recorded. Once the tracks were completed, the band and producer George Martin spent time organizing the best order to maximize the album experience. With a Little Help From My Friends isn’t a stand-alone track, but a segue from the titular opening track.

In a similar way, A Day in the Life cannot be fully appreciated without being the concluding track on the album. Everything builds toward that conclusion, with its crashing piano chord. Removed from the sequencing and downloaded as individual tracks, they become merely random songs.

“When we recorded albums in the Guess Who and BTO,” Bachman says, “careful consideration was always given to what would be on the cover, front and back, and the sequencing of the tracks. It enhanced the overall appeal of an album.”

Looking over my own extensive vinyl collection, I can still recall where and when I bought most of them.

My record-buying experience began in early 1964 with the Beatles and the British invasion albums and singles purchased at Eaton’s second-floor record bar. By 1966, as my tastes became more discerning, I discovered the Record Room adjacent to the Rialto (later the Downtown) theatre on the north side of Portage Avenue.

It was there I was introduced to folk and folk rock, blues (both obscure and new), psychedelic rock and avant-garde jazz. I could, and often did, spend hours poring over the shelves, examining each and every album before making my purchase. Record shopping was an adventure.

Lillian Lewis Records, one block west of the Record Room, served my 45 needs with a well-stocked singles selection, including rare U.K. 45s and EPs. (For the longest time, I mistakenly thought the elderly woman at the counter was esteemed local actress Ms. Lewis.)

Occasionally, I would check out Music City, located further down Portage next to the bus depot on the other side of Colony Street, where genial Jack Skelly, a major presence in local music and a Teen Dance Party regular, ran the shop.

Once Opus 69 opened in the spring of 1969 on Kennedy Street just south of Portage, above an optometrist’s shop, it became my destination for music. Opus 69 specialized almost exclusively in rock music and had the most extensive selection in the city, including imported recordings, as well as listening stations to sample before you purchased.

“I remember the first time my friend and I did that, never having used headphones before,” recalls Grant Edwards.

“We were busy yelling to each other until one of the workers asked us to please stop yelling as no one else in the store was listening to headphones.”

Unfortunately, while owner Norman Stein had great taste in records, his business acumen was wanting, and when Opus 69 moved to the more spacious ground-floor store on Kennedy north of Portage in the early ’70s it was under new ownership. However, it continued to boast a wide selection and knowledgeable staff.

“For my Opus job interview,” says record collector Oliver Garus, “owner Mr. Glass asked me to list the first five Jeff Beck albums in order. I got the gig.”

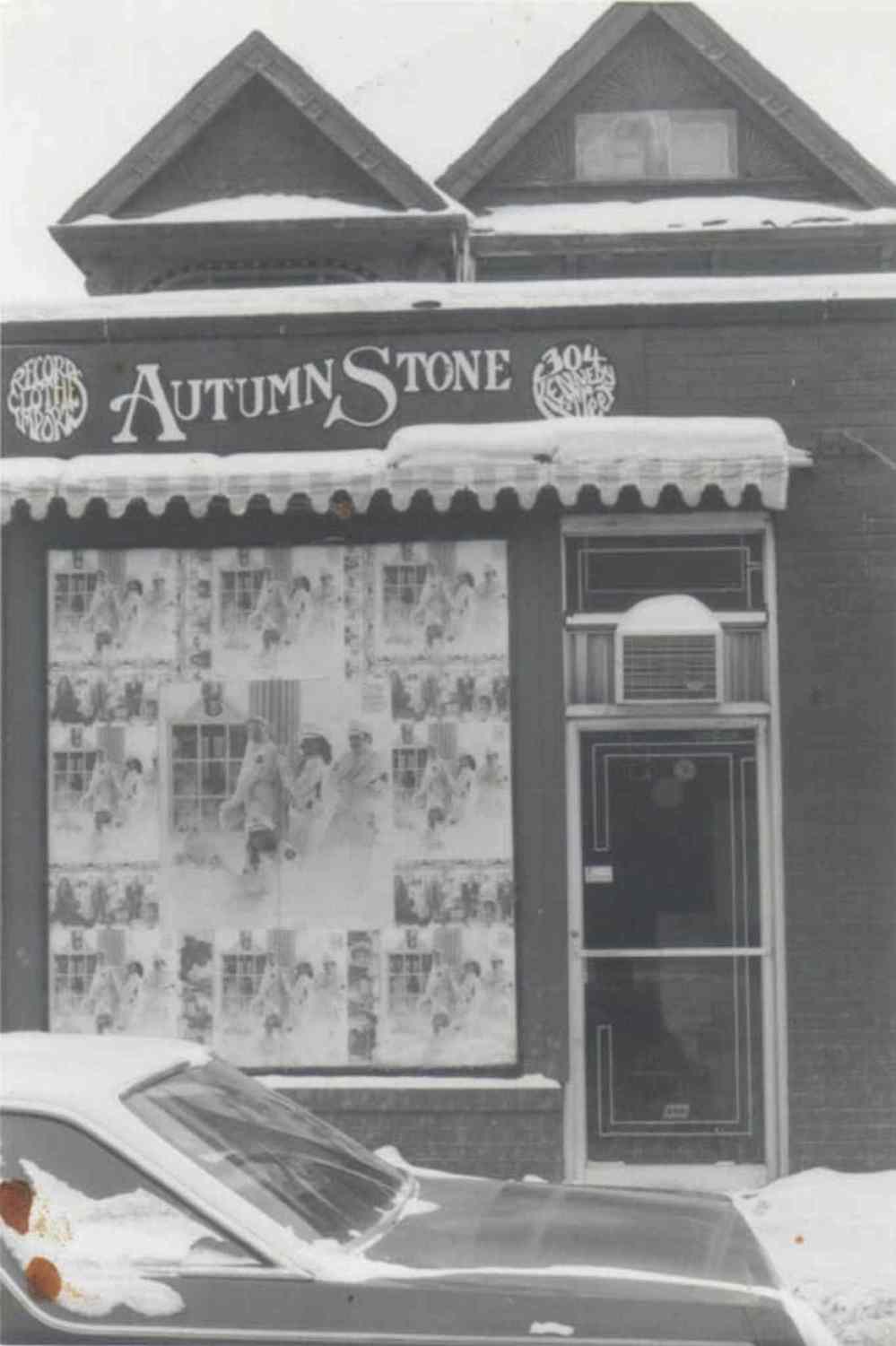

In 1972, Autumn Stone opened for business a few doors down from the new Opus 69 and became the place to go for records in the ’70s. Music guru Andy Mellen dispensed wisdom and advice to appreciative customers.

“I never tried to steer people toward music I didn’t believe in, and they trusted us,” says Mellen.

“Autumn Stone was by far the best,” Dave Kochan says.

“It was the atmosphere. You walked in, and immediately the scent of incense hit you, and then the massive speakers hit you with a wall of sound. Not deafening though, because you could always have a chat with Andy.”

The ’70s was the golden age of record shops in Winnipeg. For a time, it seemed like there was a record store on every block downtown.

“The record shops along Portage Ave and the off streets would all be open late on Friday and Saturday evenings,” Mark Corner remembers.

“That really helped bring a buzz to the downtown district.”

Everyone had their favourites. Mother’s Records at 376 Portage Ave., run by Murray Posner and Arthur Graham, began as a basement shop before relocating on a main-floor location offering an extensive selection.

“I would say some of the reasons people went there for records was the selection,” says one-time employee Kelly Copeland.

“Mother’s was huge and comprehensive, carrying as many releases for as many artists as possible in every genre, and their floor staff knew their stuff and took their music seriously. As a young teenager, the appeal for me was the cool factor of that place.”

Besides records, the Music Explosion, located on the north side of Portage, featured an upstairs black-light room with posters. Pepper Records, owned by wholesale music outlet MCTR (Thomas Rathwell), ran for many years across from the University of Winnipeg. Kelly’s sprang up on Portage at Kennedy. Opus opened the Wherehouse on the north side of Portage.

Popular Ontario chain Records on Wheels opened a branch further east on Portage, past Smith Street, that offered an impressive import section. “Records on Wheels and Mother’s were two of my favourite hangouts as a kid,” says Mike Beernaerts.

“I discovered and learned about so many bands I’d only read about in magazines who didn’t get played on radio back then (the 1980s).”

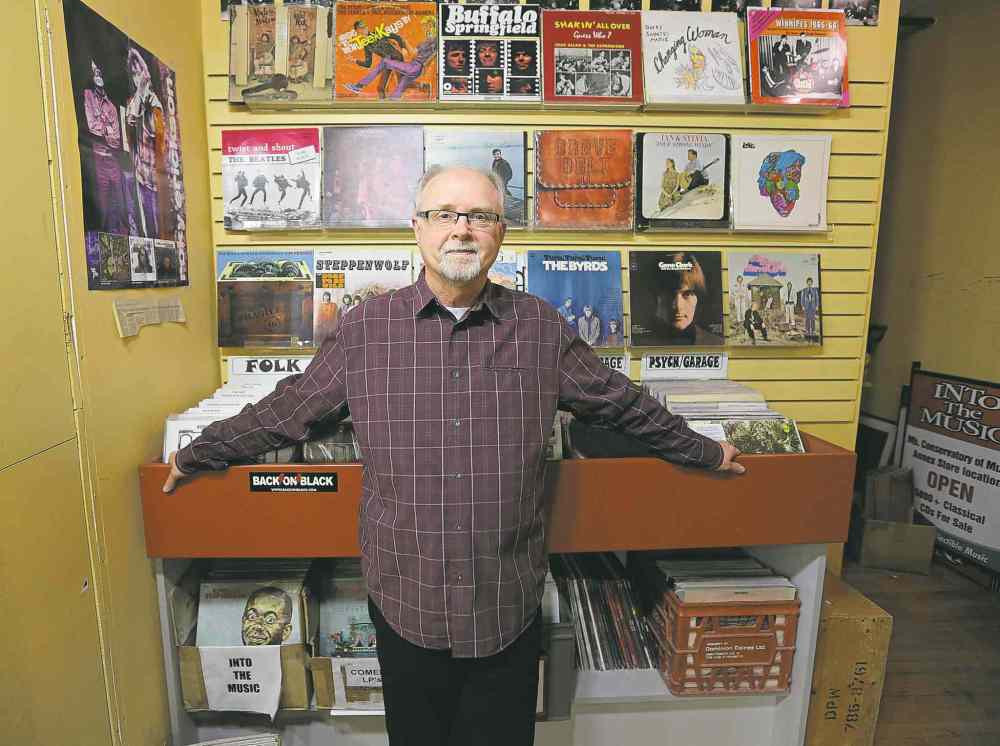

Later generations found their own favourites such as Impulse Records at Corydon and Lilac, Pyramid Records (several locations), Sam the Record Man in the Garden City mall and my favourite vinyl haunt these days, Into the Music in the Exchange District.

I parlayed my obsession with records into several jobs over the years. In the fall of 1968, at age 16, I manned the tiny record department (stocked by Campus Records) in the back of Strain’s Camera in Polo Park. After graduating from the University of Manitoba in spring 1973, I worked at Opus 69’s north Kennedy Street mega-store until I left for the U.K. I remember the rule was whatever record a customer asked about, it was always a great record.

After winding up my playing career in Toronto and returning to Winnipeg in 1976, I worked in the wholesale end of the record business at London Records in the St. James industrial area.

Finally, upon retiring from a 30-year teaching career in 2008, I worked for several months in the CD department at the short-lived McNally Robinson Booksellers location inside Polo Park. We stocked vinyl, but CDs were the steady sellers. Even by then, our customers were skewed more toward boomers, because young people downloaded their music and weren’t purchasing CDs.

But don’t tag me as stuck in the past. While I have thousands of vinyl records, I also have an equal number of CDs and download songs from iTunes. As to which format is better, vinyl or digital, there is no definitive answer, and the arguments rage on. Both have their champions and detractors.

As for me, I’ll stick with my vinyl copy of Yes’s Fragile.

Sign up for Einarson’s Summer of Love 1967 January course at mcnallyrobinson.com.

Born and raised in Winnipeg, music historian John Einarson is an acclaimed musicologist, broadcaster, educator, and author of 14 music biographies published worldwide.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, January 3, 2016 8:01 AM CST: Photos changed.