Taken by prescription drugs

As overdoses skyrocket in the city, one family speaks out about the deadly consequences

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/08/2016 (3490 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

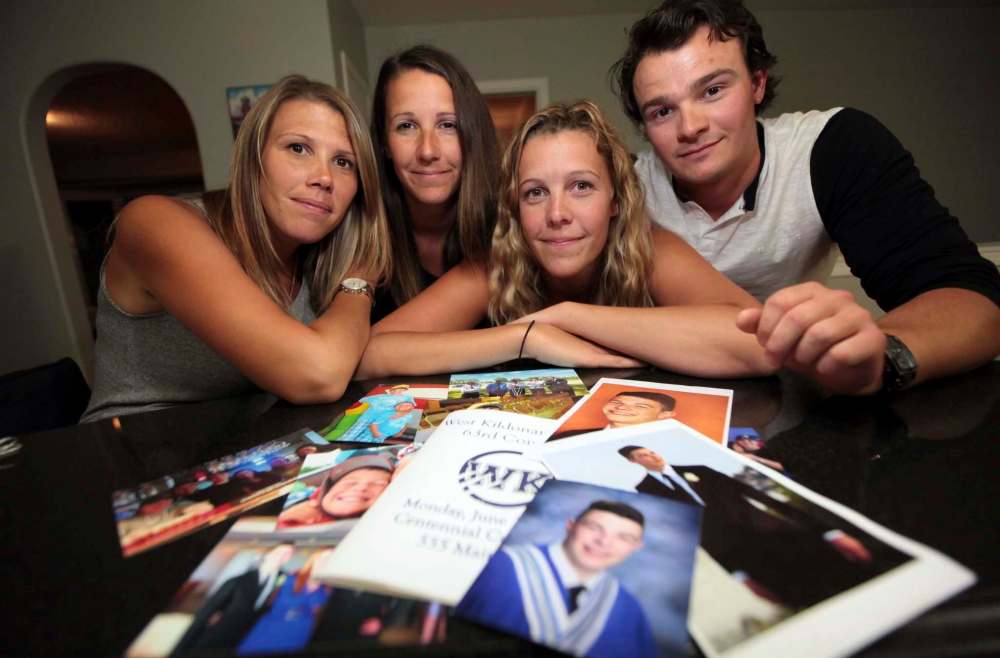

It was supposed to be the happiest moment of his life. Isaac Babinsky would proudly stroll up to the stage at West Kildonan Collegiate, collecting his high school diploma in front of family and friends.

But the 18-year-old never made it to graduation in June. He died days earlier after a night of celebration ended in tragedy.

His grieving family is speaking out to warn others and put a face to the rapidly growing problem of overdoses and prescription-drug-related deaths. Autopsy results show Babinsky had a mix of Xanax and alcohol in his system. Xanax is an anti-anxiety medication in the benzodiazepine family of drugs.

“I guess they all just went to sleep, and when they all started to get up in the morning, they went to wake him, and he just didn’t wake up,” said his sister, Krista Derksen. “Since then, we’ve now heard this is pretty common. A lot of them are doing it. Nobody thought it was that dangerous.”

Last week, federal Health Minister Jane Philpott also sounded the alarm, taking aim at what she said was pharmaceutical-industry pressure on North American health-care providers to use opioids extensively in treating chronic pain and mood disorders. These include popular drugs such as fentanyl, morphine and oxycodone.

“People need to have access to these effective medications where used appropriately, but there is tremendous risk potential. People do become addicted to them and people die,” Philpott told The Canadian Press.

In 2013, the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service responded to 1,269 overdose calls. That jumped to 1,328 in 2014 and 1,556 in 2015. There had already been 964 calls through July 26 this year, putting the city well on pace to continue the upward trend.

Although the WFPS numbers don’t specify which drugs were involved, another statistic does. They track their use of naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses. There has also been a major spike in its usage. In 2013, 307 patients received it, 348 in 2014, 418 in 2015 and already 322 through July 26 of this year.

“I’ve probably given out more (naloxone) in the past six months than I gave out in my first 10 years,” said a veteran Winnipeg paramedic, who asked his name not be published because he’s not authorized to speak publicly.

He’s also witnessed another side of the opioid problem: a family member works at a city pharmacy that was recently robbed by someone who made off with scores of prescription drugs likely destined for the black market.

“It’s nuts out there these days,” said Roland Vandal, who runs a youth-stabilization home in Winnipeg. Vandal is a former gang associate and drug addict who is candid about his troubled past, revealing all in his book Off the Ropes: My Story.

Now 14 years sober, Vandal said tragedies such as what happened to Isaac Babinsky are all too common.

“I hear lots of stories. They’re stealing prescription drugs from their parents and grandparents, and they’re using that as currency on the streets. They don’t even need money,” Vandal said.

Last winter, Winnipeg teen Cooper Nemeth vanished after a night of partying with friends. His body was found days later stuffed in a garbage bin. Another young man has been charged with his killing in what justice sources have told the Free Press was a dispute over the selling of prescription drugs such as Xanax.

Last summer, Winnipeg police issued a public alert about an escalation in the use of fentanyl, a drug that can be up to 100 times more powerful than morphine, after it was linked to a number of overdoses. Between 2009 and 2013, there were 48 deaths in which fentanyl was detected in the blood and 27 deaths where the drug was directly implicated.

“It’s such an uphill battle. The decisions you make as a teenager, they’re often so random and so impulsive. That’s some of the hardest times of our lives. Unless you have really good guidance, it’s really easy to make bad decisions,” said Vandal.

But even good guidance is no guarantee.

● ● ●

Isaac Babinsky grew up in a loving middle-class environment, surrounded by five older siblings. His three sisters are all nurses. One of his brothers is a fire paramedic in the city. His father is school trustee Mike Babinsky.

“We used to joke about how nothing bad ever happened to our family,” Krista Derksen said.

That all changed on the morning of June 19, when they awoke to a series of “R.I.P Isaac” posts that had been placed on Facebook by his friends.

Isaac had spent the previous evening in Tyndall Park, hanging out with a few friends from his previous years of going to Sisler High School. They were playing PlayStation, watching television — and apparently drinking and experimenting with prescription medication one of the boys had likely swiped from a parent. The homeowners were at the cottage for the weekend, leaving their teen son in charge.

Gordon Holens, a statistician with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, tracks all deaths where drugs are found to be in a person’s system. He said one of the difficulties can be finding out exactly what led to death.

“The challenge we have is to do a classification of these deaths. It’s not always straightforward,” he said. “When it comes to drug-overdose deaths, we’ve got three types. There are those that are suicides, those that are classified as accidents and those classified as undetermined.” He estimated out of every 150 deaths where drugs are present, 100 are deemed accidents, 25 are ruled suicides and another 25 are undetermined.

Babinsky’s family believes he died after vomiting while asleep and being unable to breathe.

“Everyone said how he was so excited to be graduating, he was happy, not messed up. It was clearly an accident, this wasn’t planned at all,” said his sister, Nicole Babinsky.

His graduation ceremony — less than 48 hours later — became a sombre affair. A video tribute to Isaac was played while all students carried a single rose up on to stage and deposited them in a vase, which was later given to family members. Two teachers spoke days later at his funeral, which was a standing-room-only affair of at least 500 mourners.

“It’s natural, especially as a teenager, to feel that they’re invincible,” said sister Mackenzie Simeonidis. She’s now heard many other horror stories, including ones from some of Isaac’s friends, about their own experimentation with opioids.

“The general consensus is lots of them don’t understand how close to death they are,” she said. “(Isaac) just wanted to live life to the fullest.”

“I feel like they think it’s cool to overdose, the fire department comes, they save you,” added Derksen. “It’s like they think prescription drugs, they’re prescribed, why would they kill you?”

A Free Press story in November 2015 chronicled how local facilities that specialize in treating opioid addiction have seen a major escalation in patients, especially among young adults. One facility in the North End is accepting up to 30 new patients per month.

Ryan Woiden, president of the Paramedics of Winnipeg Local 911, said it’s incredible what people are doing to get high in Winnipeg — especially among teens and young adults.

“Kids are mixing it with things, not realizing what can happen. They’re using it, they’re cutting it with other things. They’re putting it in juices,” he said. “Kids, nowadays, are working to try and get that high quicker, at a cheaper price, and they don’t understand the consequences.”

In British Columbia, opioid deaths are so high they’ve recently declared a public health emergency. Officials are starting to put naloxone units on the streets for members of the public to utilize should they come across someone suspected of overdosing. Police also started carrying the drug in their cruiser cars.

Woiden said he’d like to see similar developments come to Winnipeg, much like how defibrillators are commonly seen in public.

“They’re saving people’s lives. I’ve got no problem with (naloxone) kits everywhere,” he said.

Woiden believes there are three reasons for the spike: the amount of uncontrolled, prescribed narcotics in the community, the form they are in makes it easy to abuse, and a lack of public education.

“I wish I could show people what it does to them. None of it is pretty,” he said.

Jake Babinsky said his younger brother’s death should serve as a “wake-up call” to the community.

“It’s the worst thing in the world. I wouldn’t want to wish it on anybody,” he said.

“It can happen to good, nice, ambitious kids,” added Derksen.

Isaac had dreams of one day being a firefighter and volunteered every Sunday at the firefighter museum downtown. He also had a connection with society’s “underdogs,” such as special-needs students he went out of his way to bond with.

“We always talked about how we didn’t know what he would be, but he would do something amazing. He was going to surprise us all,” said Nicole Babinsky.

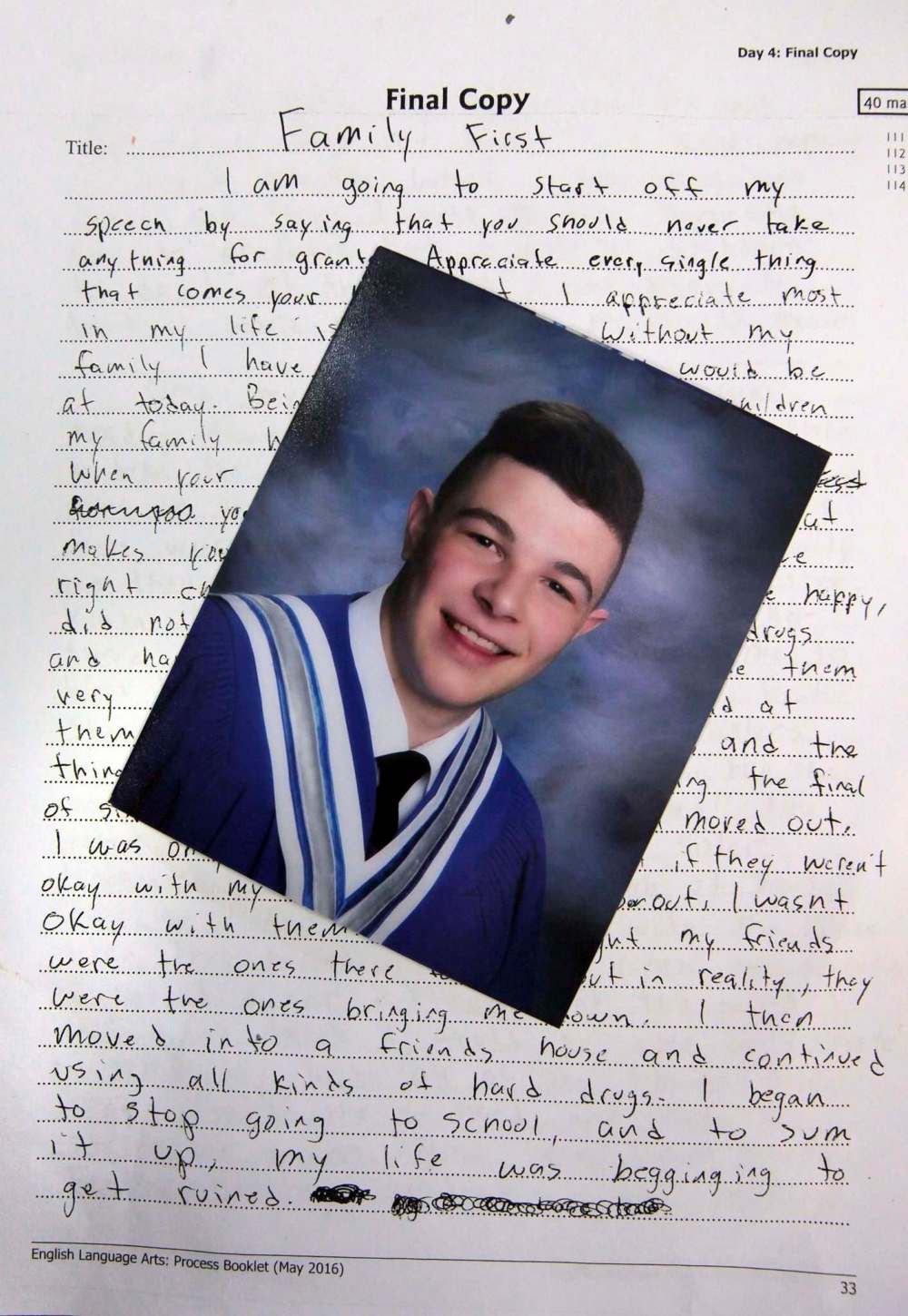

But Isaac’s biggest love was his family. He got a “Family First” tattoo and wrote his final English essay this past spring on what his family meant to him in overcoming previous struggles that included trying hard drugs. His siblings have now all got the same tattoo, while the essay was read aloud at his funeral.

Family members said they initially felt anger but quickly moved on from that emotion.

“Isaac wasn’t vulnerable. I would be more upset if he was a shy, anxious kid who got pressured into something,” said Derksen. “But I know if he’s anywhere looking down, he’s regretting things, like this is not where he wanted to go. He was right on the brink of doing some really good things.”

They are now focusing on education.

“I hope kids realize this isn’t just you having fun, you could be absolutely devastating your entire family… ” said Derksen. “If Isaac knew that was going to happen… never mind for his own life’s sake, but he would never want to do anything like that, he would feel so guilty about everything and never want to hurt everybody like that.”

“It would really suck to know this happened and it didn’t help anybody. We don’t want it to be a secret that’s swept under the rug so that you hear about more kids dying of overdoses. That would break my heart,” added Nicole Babinsky.

mike.mcintyre@freepress.mb.ca

Mike McIntyre is a sports reporter whose primary role is covering the Winnipeg Jets. After graduating from the Creative Communications program at Red River College in 1995, he spent two years gaining experience at the Winnipeg Sun before joining the Free Press in 1997, where he served on the crime and justice beat until 2016. Read more about Mike.

Every piece of reporting Mike produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, August 7, 2016 12:21 PM CDT: Changes headline; adds information on benzodiazepines.