A mother’s heartache

Waylon Smith vanished 10 years ago. This week, his mom embarked on a walk of hope and planned a feast in honour of his birthday

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/11/2016 (3364 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

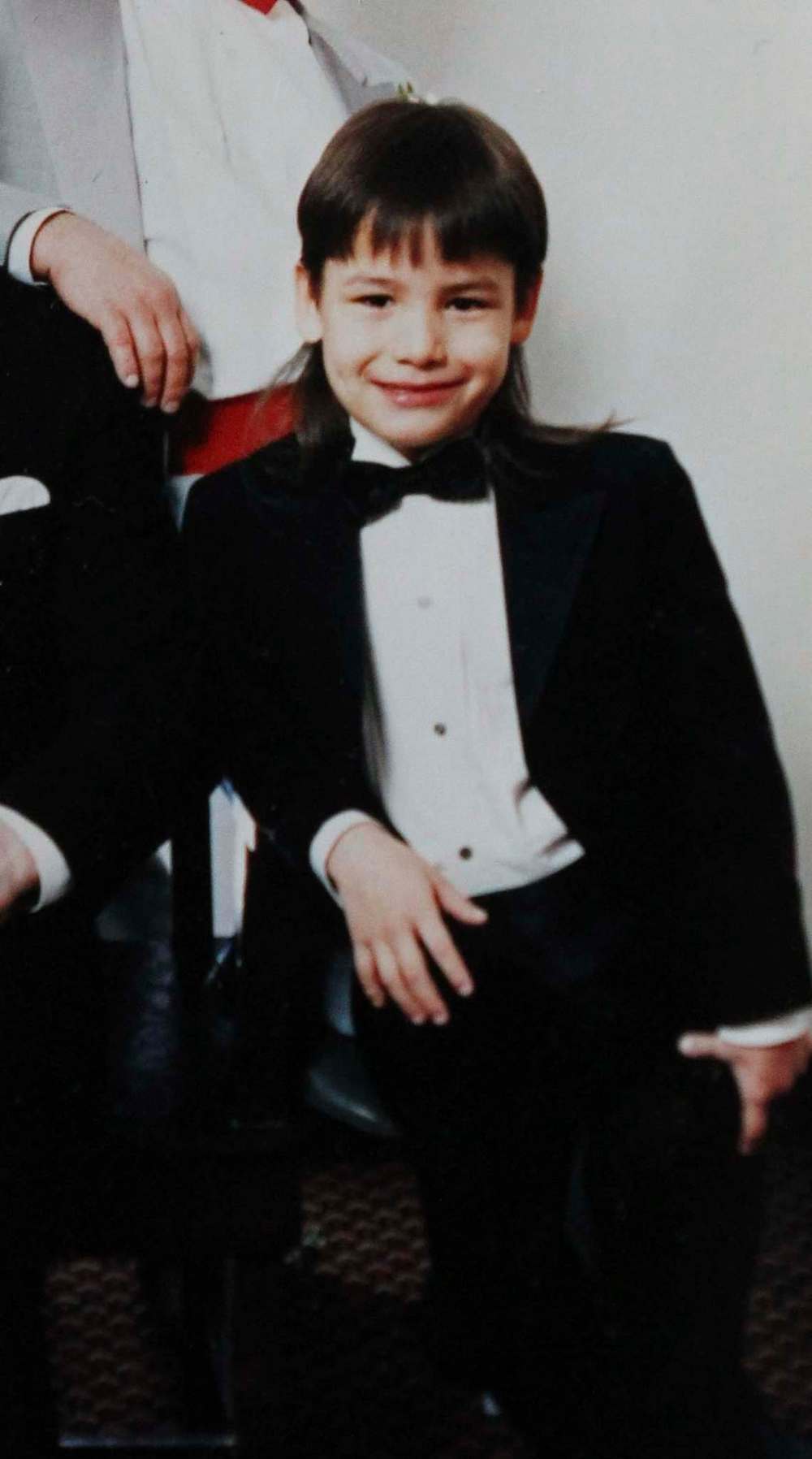

On the day Waylon Smith turned 17, his mother set out a feast. She bought him a cake. The family came together, Debra Sinclair remembers, which is a blessing because it would be the last time she celebrated her eldest son’s birthday.

Three months later, Waylon went missing. One year passed, and then another. Sinclair waited for Waylon, aching to hear him walk in the door and greet her the way he always did, with a jaunty “Hello, mother.” Ten years later, she is still waiting.

It does not get any better. “Every year at this time, I always have a hard time,” she says. “His birthday is the hardest time. And the holidays don’t help because it’s not the same. Then January is the anniversary. I just miss him so much.”

But this year is different. On Sunday, Nov. 6, Waylon would be 28 years old. To mark the day, Sinclair plans to complete a march from what is left of Lake St. Martin, where she grew up and Waylon went missing, to Winnipeg.

It’s a long journey, about 260 kilometres down Highway 6. Sinclair, set to leave Thursday, was not walking it alone. She will be surrounded by two dozen people or more — friends and family and supporters. And she will carry her hope.

When they arrive in Winnipeg Sunday, Sinclair plans to hold a feast. A birthday party, after all these years. “The whole reason I’m doing this walk is to erase a little bit of the pain,” she says. “I want him to know that he’s not forgotten.”

There’s another birthday Sinclair remembers, the one when Waylon came into the world. He a “miracle,” after doctors told her she might not be able to bear children. So when he was born, a tiny newborn with wispy dark curls, she was overjoyed.

“I just thought to myself, ‘somebody actually belongs to me.’” Sinclair says of that day. “I wasn’t alone anymore.”

For the next 17 years, Waylon brought her joy. He was a happy kid, she says, and a talented artist. She holds up two pictures he drew in black ink, the line work exquisite. In one, perfect silhouettes of tiny animals frolic inside the outline of an eagle.

He got paid for that drawing, when a youth organization chose it for their greeting card. Sinclair framed the original.

Flash forward to Jan. 7, 2006. Sinclair was returning to her apartment after a trip to the store. She ran into Waylon, who was living with his grandma, at the corner of Selkirk Avenue and Charles Street. She asked where he was headed.

“I’ll be right back, Mom,” he said. “I’m going for a walk.”

Sinclair nodded. “OK,” she replied. “I’ll wait for you.”

Those were the last words she ever exchanged with her son.

When he didn’t come to visit that night, she figured it was because it was too cold. A few days later, she discovered he had hitched a ride to Lake St. Martin and was staying with her father. She asked family members to bring him home.

By then, Waylon had been diagnosed with depression. He had changed in recent months, Sinclair thought. He “wasn’t Waylon,” sometimes. He would say strange things and lost his appetite. He was paranoid that someone would hurt him.

One winter morning, police found the teen wandering around St. Vital on a frigid winter night, looking for a place to warm up. He wasn’t wearing socks. When police brought him home, his usually sleek ponytail was undone and messy.

So when Sinclair learned he had gone to stay with his grandfather at Lake St. Martin, she was alarmed. She still doesn’t know why went up there; they hadn’t gone as a family since the boys were young. There were people there she didn’t trust.

After a few days passed, and nobody brought Waylon home, Sinclair decided she’d go and get him herself.

“Oh,” a family member told her. “Waylon hasn’t been around for a few days.”

Sinclair’s stomach dropped. “Something inside me had this ugly feeling,” she says.

The timeline of his disappearance isn’t clear; several people believe they were the last to see him. Either way, he never came back. He never called. As best as Sinclair has been able to pinpoint, the last time he was seen alive was Jan. 17.

There are rumours, though. Even now, they swirl up and slip through her fingers. She knows Waylon was struggling with depression, but she doesn’t think he would have run away. And the rumours have congealed around the same names.

So far, Sinclair has heard someone killed Waylon, and buried him in the townsite, or down Waterhen Road, or under the school. The latest version of this story is someone cut a hole in the lake ice and dropped his body through.

That latest rumour doesn’t ring true. “Who does that?” Sinclair says, shaking her head. “I’ve seen it done in a movie.”

If there is any truth to the rumours, Sinclair doesn’t know. What hurts is the not knowing. What scares her, is not knowing whom to trust. “I’m not accusing anybody,” she says. “I figure, God will take care of that. I let that anger go.”

There is something else: in May 2011, the province deliberately flooded Lake St. Martin, opting to wash away the First Nation to ease pressure from a larger flood. At that moment, some of Sinclair’s hope to find Waylon washed away, too.

“I was mad at everybody for a couple of years,” she says. “I didn’t go up there. I had a hard time the first time I went back there. I blamed everybody, when he first went missing. I was like, ‘Why didn’t you just bring him home to me?’”

The old Lake St. Martin is gone now. A rebuild is underway, a short distance from the old townsite, but progress is slow. Its residents are still displaced, their lives thrown into disarray. Since 2011, at least five evacuees have committed suicide.

Sinclair had moved to Winnipeg when she was 16 to go to school, so the flood didn’t impact her as directly. But long before the flood, her family knew pain.

In 2003, Sinclair’s cousin Rodger Ledger was 14 when he was killed after being hit by a thrown shovel; a 13-year-old youth was charged with manslaughter in his death. The two boys were close, and Waylon was a pallbearer at Rodger’s funeral.

Just seven months after Waylon disappeared, Sinclair’s cousin Myrna Letandre vanished, too. In 2013, her skull was found hidden in a Point Douglas house. She had been murdered by a boyfriend who went on to marry and kill a woman in B.C.

“When her sister phoned me and told me they found Myrna’s skull, I just fell to my knees, and I cried,” Sinclair says. “And then I think, how am I going to react when they tell me Waylon’s been found?”

That’s the scary part. The waiting is agony, but the “found” could be a whole other thing. Still, it would at least be an ending, an answer. Because though 10 years have passed, the hurting doesn’t change. Time doesn’t heal it, and it never goes away.

Prayer though; that helps. So every day for 10 years, Sinclair prays. She comes from a long line of preachers: two of her uncles, two great-grandparents and her godfather were all members of the clergy. So in faith, she finds hope.

“I just pray for peace and mercy and just to bring my baby home,” she says. “Let me do right by him.”

The hope is this: someone who knows what happened to Waylon will see her walk. And maybe, in seeing her heart, they will have a change of their own. Maybe they will come forward and tell her or tell police what they know.

“I want someone to say something that will help me,” Sinclair says. “Part of me says he’s not coming back, but the other part’s got hope. I always ask for strength. Even if he’s not with us anymore, I’ve still got to find him and give him a proper burial.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.