Perils of using ‘plain language’ in legal writings

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/03/2019 (2439 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

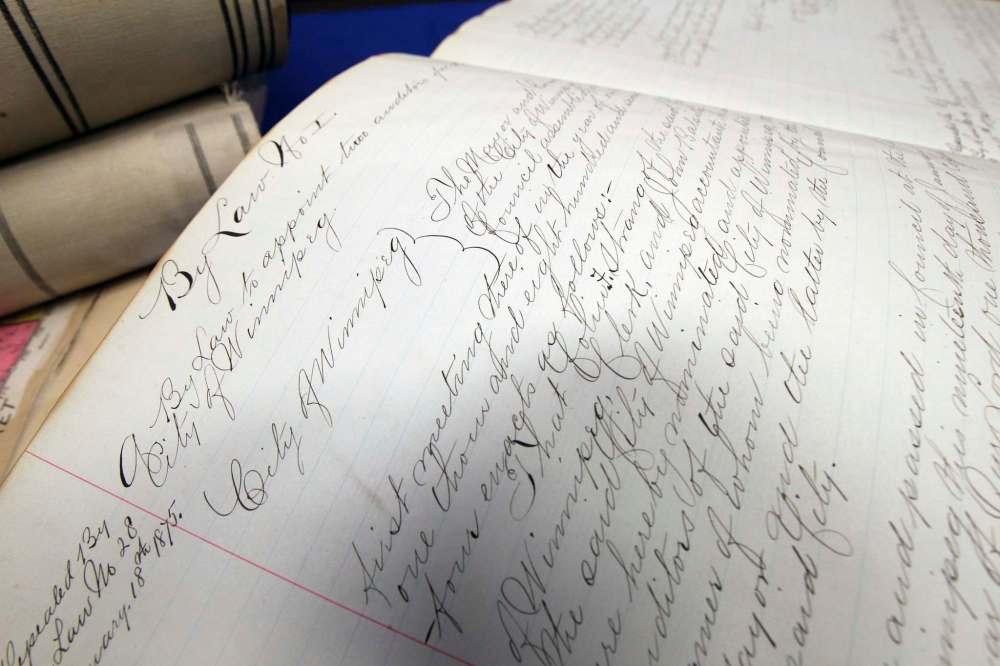

DURING the past decade, a “plain language” movement has gained traction in Canadian legal circles. Sundry law schools, bar associations and legislatures have promoted an overhaul of legal writing — everything from laws and regulations to judgments and contracts — to make it more comprehensible to the average Joe.

The intention is commendable — help people make better-informed legal decisions and avoid misunderstandings that result in litigation or liability. But plain-language-law initiatives come with their own comprehension problems.

Sometimes they’re spearheaded by people who have limited understanding of legal issues, or who disregard legal distinctions of long-acknowledged importance. And sometimes they’re seized upon by opportunistic politicians more concerned with re-election than linguistic transparency.

New York state pioneered plain-language legislation in the 1980s. It experimented with jettisoning historically settled and accepted legal language in favour of a more minimalist approach to legal drafting. The state went so far as to hastily enact a law that required clear writing in consumer contracts, with offending companies or individuals subject to a fine if they failed to use simple language.

But what constituted a sufficiently obscure document to trigger the penalty wasn’t clear in the ostensibly “plain language” statute. The inevitable result: confusion, and much messy litigation. So-called “plain language” is not without its ambiguity.

Manipulating the English language to convey precisely what you mean is fraught with difficulty at the best of times. Common words carry dual, multiple or shifting meanings. The placement of punctuation marks or prepositions can alter the meaning of a sentence. And misplaced modifiers can turn what’s intended to be approved into what’s not.

Moreover, some of what plain-language exponents deride as legalese is in fact indispensable. What, at first blush, seems redundant language is often used to achieve clarity of intention and avoid ambiguity, and thereby conflict. If a contract, statute or regulation isn’t worded to unmistakably distinguish what’s agreed upon or permitted from what’s not agreed upon or permitted, people are apt to quarrel and litigate.

Bad legal writing is much like any other bad writing. Its roots lie in the same ineptitude and laziness that characterize baffling bureaucratic communications from the Canada Revenue Agency or the incomprehensible technical writing in manuals that accompany consumer-electronics purchases.

It’s not technical terms, hair-splitting definitions or even repetitiveness of language that make for lousy legal prose. Rather, blame tortuous syntax, bad grammar, a surfeit of adverbs and sentences laden with so many subordinate clauses that you forget the beginning by the time you get to the end.

Truth be told, there’s yet another reason for bad legal writing: few lawyers are trained to write properly.

Legal drafting is one of the most intellectually demanding skills required of a lawyer. At base, it’s expository writing — something once commonly taught in secondary schools and undergraduate programs, now less so — but of a highly specialized kind.

Yet it’s largely neglected in law schools. I graduated from law school without any training in it except for a first-year legal research and writing course. It was heavy on the research component, but notably light on the writing function (and even there, the emphasis was on the formatting of memoranda of law, not on writing them coherently).

I recall, as a law student in the early 1980s, raising this omission with the then-librarian at Robson Hall, the University of Manitoba’s faculty of law. My thinking was that the law librarian, of all people, would be receptive to the idea of a course that focused on clean, clear and grammatical legal writing.

I was dead wrong. He was indifferent. Shrugging his shoulders, his blunt reply: “Law professors don’t teach English.”

Proper legal drafting necessarily takes place against a background of rules of interpretation and a history of judicial decisions. These rules and decisions have created language that has been tried, tested and ultimately sanctioned in the courts. They have, over time, created some certainty as to how a document or law is to be understood.

The plain-language movement has a lot to commend it. But as in politics, so with law, evolution is preferable to revolution.

It is at our peril that we would, in wholesale fashion, dump the rules that govern legal writing in favour of a brave new world of simplified linguistic terrain.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.