‘He was one of a kind’: Mel Lastman took on Toronto elites with his brash style — and won

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/12/2021 (1387 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A little over a year ago I visited with Mel Lastman at his retirement residence on the north side of Steeles Avenue West.

We were a long way from the centre of the town he presided over as mayor for 31 wildly entertaining years, spiced with political gaffes and conspicuous consumption: the Rolls-Royce and hair transplant and in-your-face stogies, the charity balls and parties and his wife’s shopping spree, and a string of excesses and headline grabbers that kept Toronto’s high society agog.

Mel had been retired 17 years. He was frail. But his mind still pulled up events and memories from back in the day. And I kept thinking about the first time I had met him, taken aback at how small he was and how less than imposing he appeared — right up to the moment before he ascended a podium to flip the mental switch, hit the “perform” button and wow the audience.

There was no “performance” that day, just the reality of the once most powerful man in Toronto, now resigned to the end of a great run.

We didn’t talk about that. Nor his loneliness with Marilyn gone. It was a chilly day under the courtyard gazebo. Mel’s mind was still sharp. He remembered more than I figured he would. And after about 40 minutes his aide wheeled him back into the home.

I knew what he was thinking.

“I’m not afraid of dying,” he’d told me three years earlier. “I just want to die without suffering.”

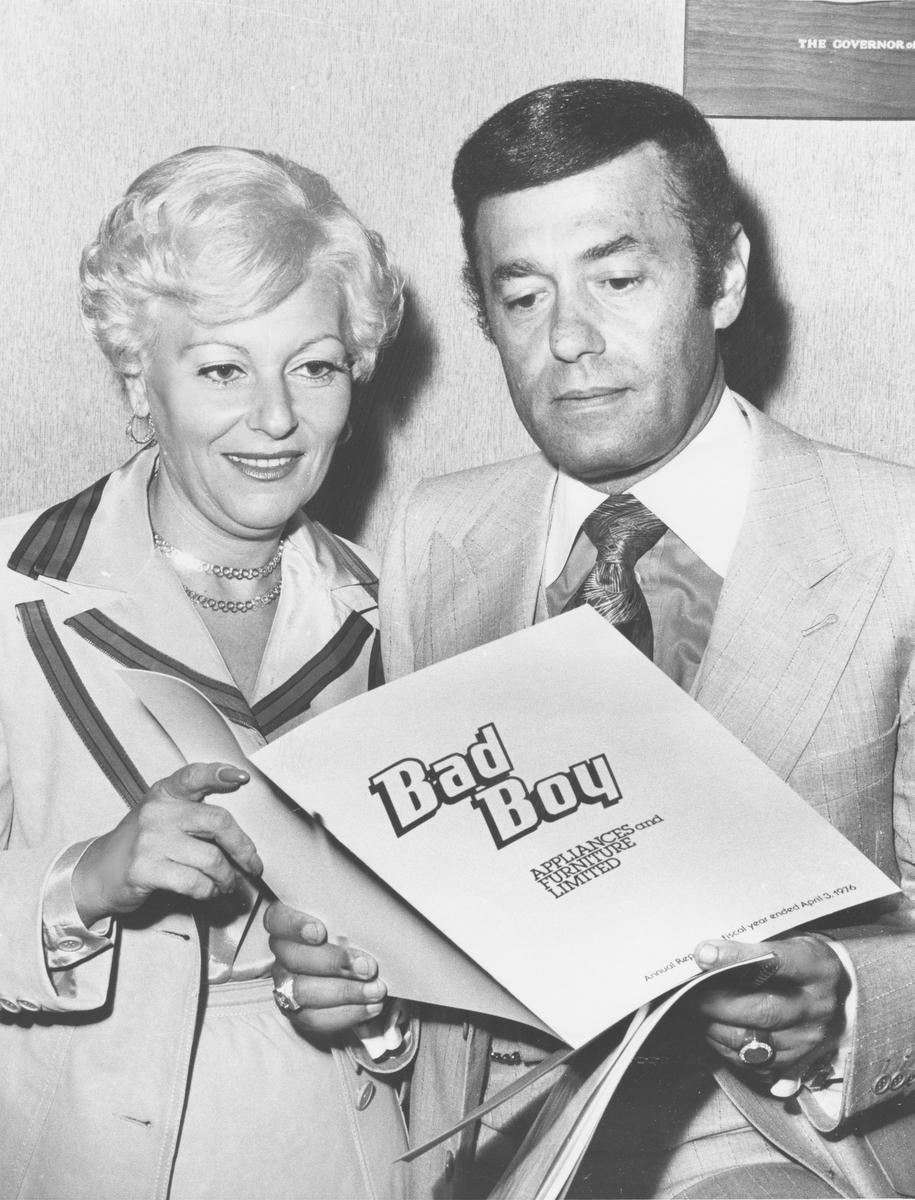

Melvin Douglas Lastman got his wish last Saturday night. “He passed in his sleep,” said Blayne, the younger son who resurrected the Bad Boy furniture chain Mel started. “They tried to revive him on the way to the hospital but he was already gone.” Mel was 88.

Before a Toronto mayor smoked crack and achieved global infamy, and the U.S. president routinely transgressed all bounds of decency; before politicians paraded as rock stars and their children commanded attention like the monarchy; before 24-hour cable television news and social media — there was Mel: King of North York, Mel. Megacity Mel. “Nooooboooody” does it quite like Bad Boy Mel.

Toronto’s royalty was headed by the flamboyant, cigar-smoking, millionaire huckster and his dilettante wife who staged two jaw-dropping bar mitzvah for their sons at a time when Toronto eschewed show-offs.

Nobody saw this brash and bombastic Mel coming when he arrived in sleepy North York in 1969 and stayed to deliver what his detractors dismissed and pooh-poohed — a real suburban downtown with two subway lines on the edge of the 401, Canada’s busiest highway. Few expected his death — suddenly in his sleep at the Sunrise Retirement Home where he has domiciled since Marilyn died last New Year’s Day.

The mayor who could turn it on and off on cue, likely died of a broken heart — never recovering from Marilyn’s death, their eldest son, Dale, told funeral mourners.

“My dad stopped living on Jan. 1,” said Dale, the big shot corporate lawyer, by way of an audio recording, as he is under COVID-19 quarantine. “His love for my mom was so strong he couldn’t bear the thought of living one day without her.”

So, just like that, Mel’s gone — and with him, the golden era of reporting on municipal politics in the Toronto region.

Allan Lamport must have been special as Toronto’s mayor who pushed for Sunday sports, and produced so many malapropisms (“If someone’s gonna stab me in the back, I wanna be there”) he’s often seen as a local answer to New York Yankee great Yogi Berra. Downtowners have been led by the Tiny Perfect Mayor David Crombie, the iconoclastic John Sewell, and female light bearers Barbara Hall and June Rowlands. Scarborough had the folksy Gus Harris and Mississauga countered with Hurricane Hazel McCallion. But there’s been none like Mel — even counting the one-term misadventures of madcap Rob Ford, the absolute zaniest, mind-boggling magistrate of them all.

Mel could be brilliant and befuddling at the same time. He was a master salesman with the gift of gab, but lacking the social graces and finesse to foster deep or lasting personal relationships with colleagues and staff that spanned 35 years of civic life.

He couldn’t walk down the street without drawing a huge following. People loved him, were drawn to him — a populist in the positive, classical sense of the word, before the Trumps of the world polluted the idea with indecent identity politics.

And yet he had so few friends, no band of courtiers or hangers-on. When Marilyn ran for North York council in the mid-1980s, her campaign team was just family and a few aides knocking on doors. It was puzzling. She lost to a school trustee.

“Who are your friends?” I asked Mel shortly after.

“I don’t have any. I can’t afford to. They always want favours and I can’t grant them,” he said, then corrected himself. “Maybe one, Paul Godfrey (who became Metro Chairman and head of Post Media) because he doesn’t ask for anything.”

Mayor Mel didn’t invent the word chutzpah, it just seems that way.

He would boast about North York getting land from the federal government, selling it twice and still owning it. He would say that you can’t sell ice to an Eskimo and promptly invent a stunt that saw him successfully peddle refrigerators in the Canadian north.

We think he was Conservative, but some of his choicest zingers were directed at Tory political leaders who failed to deliver the goodies Mel felt his citizens deserved. Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chretien was a deadbeat for failing to pay for social housing and subways in Toronto, Mel raged.

“Everything Mike Harris touches turns to crap,” he once told reporters at city hall, after the provincial Tories took another stab at his Toronto government. As premier, Harris amalgamated Etobicoke, York, Toronto, East York, Scarborough and North York to form one megacity of Toronto — a shotgun marriage so despised and contested by Mel and the political leaders and citizens of each municipality that few thought the product worthy of love.

Mel beat out Barbara Hall to win the first megacity election in 1997. After greeting the serious and venerable city hall press corps on Day One by showing of his dexterity with a bolo bat and yo-yo, proceeded to embrace the unloved child. The new city was big, starved of resources, hurriedly created and left to almost topple on its own weight. The bureaucracy saved it. And Mel knew enough to stay out of the way.

On his death, Harris would praise Mel as “a good friend, political colleague and a wonderful first mayor of Toronto.”

When the Star transferred me from the Scarborough bureau to North York in 1985, it was like landing in journalism paradise. A hotel and office tower complex next to city hall had a modern clock tower with digital chimes that were dubbed Mel’s Bells. Ratepayers were locked in mortal combat with Lastman over his plan to create the greatest downtown in the history of mankind. The city would name the public square outside city hall Mel Lastman’s Square — while he was still in office.

And, best of all, Lastman was opposed by a small group of left-leaning councillors, led by the irrepressible Howard Moscoe, who knew how to feed reporters hungry for city hall “news.”

When some councillors wanted to name a new stadium after Lastman, it was Moscoe who killed the idea with a motion to name it after Terry Fox, fresh in the minds of Canadians for his Marathon of Hope against cancer. The ensuing debate killed the naming idea.

They clashed over a new slogan Mel wanted: “North York: City With Heart.” Go tell that to the residents in the west end of the city, like Jane-Finch, where social and community amenities were in short supply, Moscoe said.

A councillor proposed a new flag for North York and Moscoe showed up with five designs of his own — one of which had Lastman peddling $3 bills. Mel was not amused. North York never did get its new flag.

Suitably fuelled, my career took off. My first major news feature centred on ratepayer opposition to replacing a rose garden at Yonge and Empress, with an office tower complex — right on top of a subway station. The matter went to the dispute resolution body, Ontario Municipal Board — and the citizens lost.

But there were fights about loss of sunlight, traffic penetration, property values, congestion and those damn developers. Long before most of us could see the trumpeted downtown, Mel had it figured out — always grander and bigger and glitzier than it turned out — but far beyond what the naysayers imagined.

“Hey, come, let me show you this,” he would summon me into his office and wax on about some proposed development that promised massive palm trees in the lobby of an office complex. “It’s the greatest thing in the world — but you can’t write about it yet. I’ll tell you when.” The promises would come due, day after day, to feed the media beast.

When ratepayers massed against his downtown plan, Mel invited them to select a few reps to document their concerns and negotiate a remedy. The residents wanted to protect the residential neighbourhoods on either side of Yonge Street between Hwy 401 and Finch Avenue. George Belza became one of the go-to community spokesmen. He announced a deal in which Mel promised to build a ring road to keep traffic from penetrating into the local streets.

The complaining residents made out like bandits. Property values skyrocketed on their tiny bungalows. Local streets remain protected today from Yonge Street traffic intrusion.

Through all this, North Yorkers had unprecedented access to their mayor. Mel hosted a weekly call-in show on Rogers Cable where citizens complained about any service deficiency or other problem and Mel guaranteed a fix. Citizens loved it. They could call out non-performing city workers and Mel could still boast about unparalleled North York service.

Garbage was picked up twice a week. Snow didn’t stand a chance when it fell in North York, Mel boasted. “We clean the snow before it hits the pavement,” he claimed. Add the fact that only in North York did the snow trucks clear the piled-up snow that snow plows left in front of cleared-out driveways, and what was there not to like about living in North York?

That kind of shtick worked well in North York, but the intelligentsia did not welcome this high school educated furniture salesman and carpetbagger as the mayor of the sophisticated, amalgamated city on Jan. 1, 1998.

It’s easy to sympathize with the underdog — even a millionaire mutt — and especially one looked down upon as a country bumpkin. So, as a journalist from the suburbs, I often had the added satisfaction of watching Mel beat the downtown crew at their own political games.

Who would have imagined it would be Mel Lastman, Prime Minister Jean Chretien and Premier Mike Harris — the Three Amigos — who would strike a deal to redevelop the moribund waterfront — the lost, no-go treasure of a place since the port fell into disuse.

There was homophobic Mel — riding in the Pride Parade and having fun with water balloons and hoses.

There was Mel, learning on the job what it means to lead a diverse and complex city with real issues — like homelessness. Wasn’t this the guy who said, during the 1997 megacity election, that there were no homeless people in North York, only to have a woman die in a North York bus shelter? Now, schooled by the likes of Jack Layton and other councillors, Mel is standing in council, supporting the call to declare homelessness a national emergency requiring federal attention.

He had many faults. He was against banning smoking in restaurants until the health benefits were way too obvious. He created the first mayor’s race relations committee, but don’t mistake that for someone with an understanding of critical race theory. He wasn’t a reformer. He saw what his constituents complained was broken and didn’t mind bundling his way to a solution — so long as he got there, all the time forging compromises.

In the end, Mel achieved much, considering how little he started with. Unprepared to navigate the nuances of an emerging and most diverse and multi-everything metropolis, Mel did better than expected. To demand more is what we do as taxpayers. To expect more than Mel delivered is to apply an unreasonable standard.

His second term as megacity mayor was mainly a disaster. He couldn’t practise his brand of retail politics because his new municipal mall was way too big. We learned of his extramarital affair and secret sons. In typical Mel-speak, he questioned the existence and significance of the World Health Organization in a disastrous 2003 CNN interview on the impact of SARS on Toronto. He sandbagged any chance of the city getting the 2008 Olympics when he told a Star reporter that he wasn’t relishing a vote-hunting trip to Mombasa, Kenya, haunted by a recurring dream of finding himself in a boiling pot with natives dancing all around. Oops. At the International Olympic Committee session to vote in the winner, the Toronto contingent kept Lastman hidden from sight.

Citizens adore the politician as fighter and Mel owned the brand of the overmatched David fighting the political goliaths on behalf of the little guy. That was his secret. When he said outrageous things, tripped himself up and then had to apologize, the people forgave him. He was their guy.

“I was always in awe of his intuitive sense of politics — what he could get away with doing and saying,” said Coun. John Filion, who covered Mel as a Star journalist and then sparred with him as a school trustee and councillor for 20-plus years. “He was one of a kind.”

Three years ago Mel and Marilyn would still go for walks near their St. Clair-Yonge condo. And the drill would be the same.

“Everybody stops me,” Mel said. “They like the idea that they know who I am, but I don’t like to get into conversations. One woman asked me about a truck that’s bothering her…What can I do about the truck? I told her to call 911.

“I am not what I was. I am what I am. Just a little taxpayer.”

Not surprisingly, only partially right.

Royson James is a former Star reporter and a freelance contributing columnist based in Toronto. Reach him via email: royson.james@outlook.com