Small-town spirit deeply rooted As the community of Darlingford celebrates its 125th anniversary, residents young and old come together to honour the past and build for the future

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/01/2024 (644 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

DARLINGFORD, Man. — The story of a place can be found in its architecture.

The Monument of Lysicrates in Athens (334 BC), say. Or the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Monument in Manhattan, N.Y. (1902). Or Darlingford Memorial Park (1921), in Darlingford, Man., a pretty postage-stamp community tucked away in southern Manitoba’s Pembina Valley.

At first blush, these three structures, in three very different places, may seem like random examples. But they share a common thread that spools from ancient Greece to the Canadian Prairies, and that thread is the design sensibility of the late architect Arthur Alexander (A.A.) Stoughton, the founder of the School of Architecture at the University of Manitoba.

Stoughton designed the war memorial in Darlingford roughly 20 years after his firm designed the American Civil War memorial in Manhattan, itself modelled after the Monument of Lysicrates.

But Darlingford (pop. 200, according to best estimates) is not Athens or New York City. So how did a Gothic Revival-style memorial, and the only free-standing building in Manitoba dedicated solely to honouring war veterans and casualties, end up here?

The story of Darlingford Memorial Park begins not with architect A.A. Stoughton, but with a local farmer, businessman and politician named Ferris Bolton.

Bolton lost three of his sons in the First World War over a three-month span in 1917: 23-year-old Wilbert “Bert,” 21-year-old Harold “Harry,” and 19-year-old Elmer. Bolton envisioned a place to honour his sons and those who served with them, and donated the land on the western edge of Darlingford, at the corner of Mountain Avenue and Bradburn Street, for the memorial, which was completed in 1921.

Many veterans from Darlingford and the surrounding area served in both the First and Second World Wars, their names etched in gold on the black marble tablets inside the memorial building.

Eighteen men were killed in action, including Bolton’s three boys, and two others died in service in the First World War; eight were killed in action and four died in service in the Second World War — a disproportionate loss for a community this small.

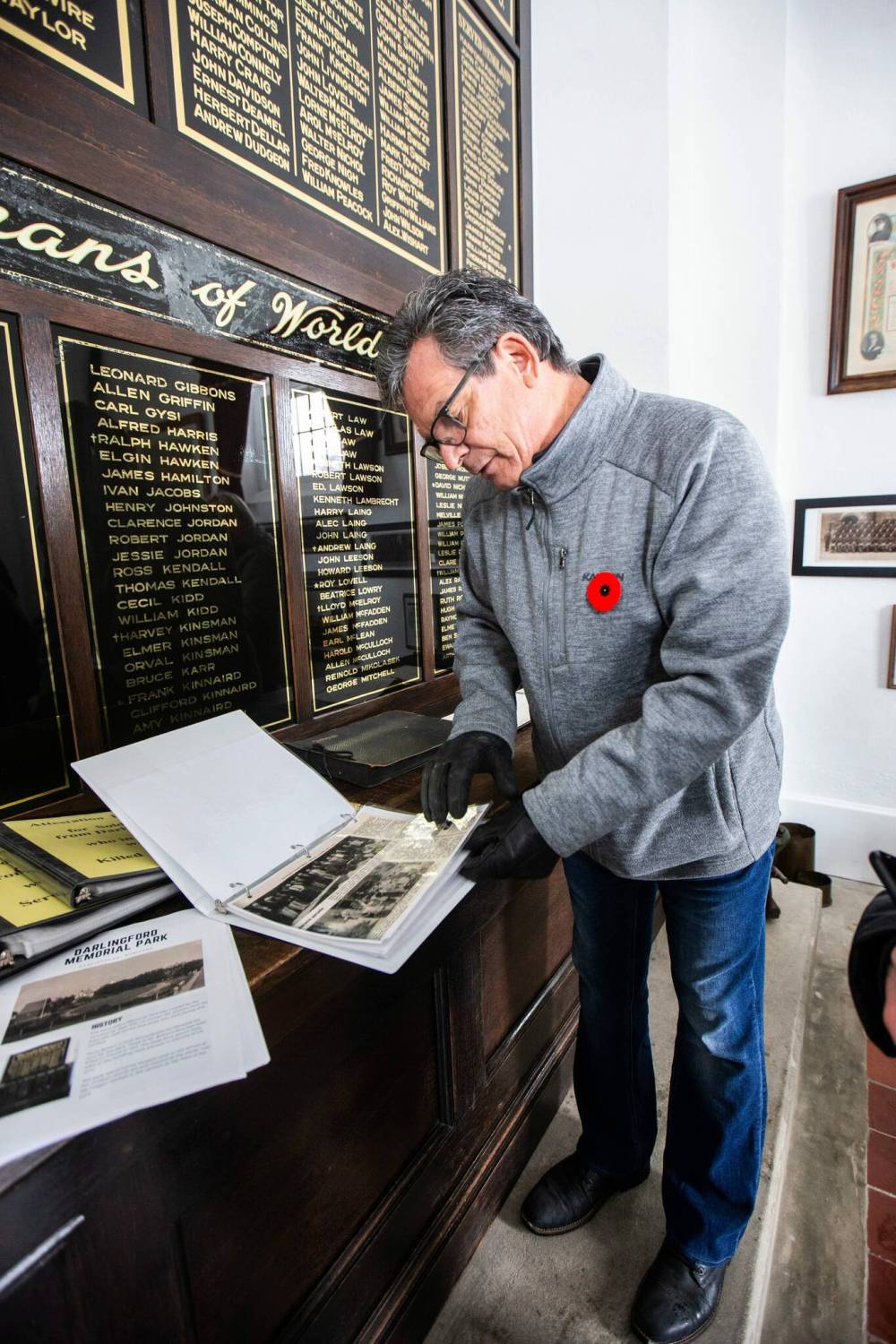

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Brian McElroy, chairperson for the Darlingford Memorial Park Committee, combs through artifacts in the war memorial building.

“The catchment area for Darlingford was six or eight miles wide and 20 miles long, so that took in 200-plus men and women enlisting in the war,” explains Brian McElroy, chairperson for the Darlingford Memorial Park Committee. “Lots of families, lots of communities, lots of people take ownership of this place.”

More than 100 years later, many people, such as McElroy, also take stewardship of this place.

McElroy, 61, has been involved for decades — “like most small towns, if you’re on a committee you’re on it forever” — and has no shortage of passion about all things related to the park, which was designated a Provincial Heritage Site in 1992.

It’s a blustery morning in late fall, and the first major snowfall of the season has blanketed Darlingford in white. In the basement of the school — now the Darlingford School Heritage Museum and a historical site in its own right — various community members belonging to various volunteer committees have assembled to talk to a reporter.

There’s McElroy’s wife Myra Amy-McElroy, 67, who is also involved with the church. There’s husband and wife Glen, 63, and Shannon Holenski, 62, retired farmers who also work with the museum. There’s Harvey Kinsman, 71, and Wilf Klippenstein, also 71, who grew up here. All of them have deep ties to the community.

Everyone’s a bit fuzzy on the exact population of Darlingford — 200 and change is the best estimate — but everyone seems to know there are 86 houses. A popular game at community coffee meetings, Shannon Holenski says, is Who Lives In So-and-So’s House Now?

“I remember (the population) being 100 when I was growing up,” Kinsman says.

“It was always 100, it never changed,” Shannon Holenski jokes.

These days, Darlingford also functions as an affordable bedroom community for nearby Morden, which is located 21 kilometres east, a straight-shot down Highway 3. But Darlingford is more than a place to hang one’s hat.

ROB NICHOL PHOTO Darlingford holds its remembrance service in the summer when the park’s gardens are in full bloom.

The people here volunteer an incredible amount of time, energy and skills to tending and caring for Darlingford’s heritage sites, including the memorial park, and keeping traditions alive — including what is arguably the community’s most defining tradition, the annual community remembrance service, which takes place in Darlingford Memorial Park at 11 a.m. on the first Sunday of July, when the grounds’ gardens are in full bloom.

The older generations seated around the table express concerns that interest in preserving these traditions, and this community-focused way of life, will wane. “I just want to see the small town survive,” Glen Holenski says.

But younger residents, such as LUD (Local Urban District) committee member Jennifer Ching-Faux, 38, are picking up the mantle. Her four-year-old son Kip and two-year-old daughter Sienna are growing up, just as she did, right here in Darlingford.

“What keeps me involved in the town would be these two right here, obviously,” she says. “My family’s here. I didn’t see myself coming home, ever, but now that I’m here, there’s no question about it. What we do is give our kids something to come home to.”

“We have to do these things. If you don’t, you lose them. And then what?”–Jennifer Ching-Faux

This is a big year for Darlingford: 2024 marks the community’s 125th anniversary. The annual remembrance service is almost as old as the community; this July’s, which will be held on the second Sunday this year, will be the 102nd.

“We have to do these things,” Ching-Faux says firmly of her community’s traditions. “If you don’t, you lose them. And then what?”

Darlingford Memorial Park is beautiful in the summertime. But Stoughton’s solemn, chapel-esque building cuts a striking figure in the winter.

For historians, the memorial is a unique example of Gothic Revival-style architecture. But for the kids who grew up here, it was the world’s greatest playhouse.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The war memorial building in Darlingford was designed by architect A.A. Stoughton, the founder of the School of Architecture at the University of Manitoba.

“For years and years, this place was never locked,” says Amy-McElroy, who grew up in Darlingford along with her four sisters. “We could come in here and have a look around. As little girls we always used to play over here.”

Still, the children of Darlingford knew to treat the memorial with reverence and respect, owing to the fact that many of them participated in the floral tribute.

The floral tribute sees children place flowers on two white wooden crosses, in honour of those who lost their lives. It’s one of the hallmarks of the July remembrance service, and has been going strong since the first service a little over a century ago.

“One of my first memories was just really wanting to be able to carry one of those little bouquets of flowers and put them on the cross,” Amy-McElroy recalls. “The local ladies would make bouquets from the peonies gathered from neighbours’ gardens.” Amy-McElroy is the fourth of five girls, and she watched her older sisters participate. “I could hardly wait to do it,” she says.

Now, Amy-McElroy oversees the children’s participation in the floral tributes, a post she’s held for over 30 years.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Myra Amy-McElroy grew up in Darlingford with four sisters. The memorial was like a playhouse for the town’s children.

“For me, that’s really important, if I can pass that on to the children,” she says. “And that we can keep that part of the service going and that we can help to instil that kind of respect in young people.”

Some of the children are in the fourth and fifth generations of their families to participate in the floral tribute.

“I’m a third-generation flower carrier,” Ching-Faux says. “Kip is now the fourth. He broke all the rules. Myra says you have to be four years old to participate. Well, Kip has been doing it since he’s two, so he’s got his third service under his belt. He knows his mark, every time.”

Klippenstein is the seventh son in his family. He attended school in Darlingford for grades 1 through 8 and vividly remembers participating in the floral tribute. “I was very proud to do that,” he says.

Now, he helps plant flowers that populate the park grounds, originally landscaped and designed by the Morden Experimental Farm and meticulously maintained by the community.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Jennifer Ching-Faux (top left), Myra Amy-McElroy, Wilf Klippenstein, Harvey Kinsman, Brian McElroy, Shannon Holenski, Glen Holenski, Sienna Faux (2, bottom left), and Kip Faux (4, bottom right) belong to various volunteer committees.

“I only have two brothers left alive,” Klippenstein says. “They both served in the Canadian Armed Forces, one of them for 25 years, that’s Stan, and my brother Ed served for 36 years. I also participate to honour them.”

Inside the memorial building are all manner of artifacts, including a German 7.92-mm Maxim Spandau MG08 machine gun that had to be relocated from outside the memorial to inside after it was stolen in 2012 and recovered in 2014.

But the focal points are the two black marble tablets bearing the names of Darlingford-area veterans.

“All of us probably have somebody on there,” Kinsman says, scanning the wall. “What I make sure our kids come and look at… here, that’s my dad and two uncles.” Orval, Harvey and Elmer Kinsman.

Kinsman grew up in Darlingford. He was raised by his grandmother who had three sons serve in the Second World War. Her son Harvey was killed in action, the uncle for whom Kinsman is named. “Those ties are always there,” he says.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Harvey Kinsman has generational ties to the town.

Lorne and Arol McElroy are McElroy’s grandfather and great-uncle, respectively; Lloyd McElroy is his uncle. James and Russell Amy are two of Amy-McElroy’s uncles. And so many more.

“I’m very proud of them,” Amy-McElroy says. “I’ve just been going through family pictures, and to see my dad standing beside his brothers in uniform — I can’t imagine what it would have been like to be 18, 20 years old and everybody wanted to sign up. I know Dad was really sad because he couldn’t. He had a heart defect so he couldn’t go. That whole sense of duty, and honour to serve your country, that’s something that’s hard to believe. I would be frightened.”

Outside, along the edge of the park, there is a message on the ground worked in stone, another vision of Ferris Bolton’s. “He wanted to make sure that the kids walked by the stones on the way to school,” Amy-McElroy says.

The three words are clear, even in the new snow. Lest We Forget.

While many Darlingford residents can find their relatives on the wall in the memorial, others of a certain age can also find themselves in the yearbooks over at the school.

It’s known as the Darlingford Heritage Museum now, but until 1984, the two-storey building at 197 Bradburn St. — steps away from Darlingford Memorial Park — was a four-classroom school. Built in 1910 and designed by Winnipeg architect F.R. Evans, the building retains its original features, including the tin ceilings and a rare second-floor fire escape that looks suspiciously like a water slide. “They’d push you if you were crying,” Amy-McElroy says of the older boys who were there to “help.”

Patrick Thiessen, 40, is the volunteer curator of the Darlington Heritage Museum, which contains dozens of artifacts and displays digging deep into the community’s history (and even before that). He’s also Darlingford Fire Department’s deputy fire chief.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The Darlingford Heritage Museum is located in the former four-classroom schoolhouse.

“I’ve always been interested in history and the past. I had some time, and approached the board and asked if they were looking for help and they needed a curator,” he says. “I like stuff. I like objects. I like stories. I’m a collector at heart. That fit in well with the curator role.”

Thiessen grew up in Morden, and has been based in Darlingford for 20 years. He’s another example of a member of a younger generation who is helping to preserve the past.

“When I moved here, it was a retirement community for farmers,” he says. “Now, it’s young families living here because it’s affordable. It’s a quiet community, kids ride bikes down the street — the stuff you sort of lose in big cities.”

The museum’s exhibits cover a wide swath of history, including Darlingford’s bustling brick yards, which had a short but prolific run at the turn of the last century. The Darlingford Brick and Tile Co. closed in 1914.

“It’s surprising once you get into it how much was there, and how important that location (Old Darlington) was before the railroad was here.”–Patrick Thiessen

“The brick factories that were here weren’t in operation for long, but they were big when they were working,” Thiessen says. “There’s buildings in Manitou, there’s buildings in Morden, there’s buildings in Darlingford made from this brick.” Including the Darlingford Heritage Museum.

A particular point of fascination for Thiessen was the existence of Old Darlingford (1880-1887), which predates the current village. “I didn’t know almost anything about it when I started. It’s surprising once you get into it how much was there, and how important that location was before the railroad was here.” There’s nothing left of old Darlingford now, which was two miles southwest of present-day Darlingford; that land has been cultivated.

Visitors to the museum can pop into a replica classroom as well, which brings back memories for the Darlingford residents who would have inhabited desks like these.

Some of their initials are even carved into the Darlingford bricks outside.

Built in 1908, the Zion Calvin United Church at 3 Dufferin St. is another gem of a heritage building that is still in use today. “We’re very proud of our little church, for sure,” Amy-McElroy says.

The church’s pews are in a unique semi-circle configuration, and the acoustics are amazing. Singer-songwriter Cara Luft, a founding member of the Wailin’ Jennys, recorded parts of her 2012 solo album here, aptly titled Darlingford. The original bell tower, which was repaired several years ago, has a working bell.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The Zion Calvin United Church was built in 1908.

Vestiges of Darlingford’s military past can be found here, too. Framed honour rolls for those who served for King and Country in the First World War; a Sunday school memorial.

“Our home was just on the other side of the church,” Amy-McElroy says. “Again we used to play in here because the doors were always open. It was another playground for kids.”

The pews are not as full as they used be, but the church is home to a small but supportive congregation.

“It’s like everything else, right, people don’t go to church very much anymore or not as many people go to church,” Amy-McElroy says. “But we’re hoping, again, with volunteers to keep it going for a little while longer, anyways.

“We have a pretty vibrant Sunday school so again, keeping the kids involved keeps your buildings alive and keeps your community alive.”

The story of a place can also be found in its people.

“Everything in the community, almost, is run by volunteers,” Thiessen says. “The museum, the memorial park, the community hall, there’s a garden club, everything is run like that. We have 20 members in our fire department — committed, dedicated members. For a community this size, that’s not that common.”

Glen Holenski, with the museum, also points to the Darlingford Fire Department as a point of pride. “Most of them guys don’t have roots here,” he says. ”They are people who have moved here. Our fire department is, I think, phenomenal, how community-involved they are.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Glen Holenski says the town’s community spirit is reflected in all its entities.

McElroy says Darlingford’s strong volunteer spirit echoes the selflessness of those whose names populate the black marble tablets inside the war memorial.

“I think probably what bonds us together the most is that we are a group of people that are still thinking that way, ‘what can we do?’” he says.

'These are probably two of the youngest volunteers in town. Kip's been shopping for bonspiel groceries since he was six months old. And so, I hope wherever they end up, they do the same, whether it’s here or wherever'

— Darlingford resident Jennifer Ching-Faux, with daughter, Sienna

Ching-Faux is instilling that ethos into her children.

“These are probably two of the youngest volunteers in town,” she says. “Kip’s been shopping for bonspiel groceries since he was six months old. And so, I hope wherever they end up, they do the same, whether it’s here or wherever.”

While Darlingford is certainly steeped in history, it’s not stuck there. This community carefully tends to its monuments to the past, but it’s also building for the future.

That looks like the popular outdoor rink, with a new warming shack. Or the gleaming new playground structure. “Bigger than Manitou’s, I will say,” Ching-Faux says with a laugh.

”The play structure was completely community-funded, completely community-built in one day, just about, by volunteers. And people brought them lunch and supper so they could keep working all day. It’s those things, right?” she says.

“Economics have made this a bedroom community. But we can still make people care about where they sleep.”

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.