On the path of double vowels Indigenous-language classes at The Forks a gentle opportunity to learn, laugh and overcome self-consciousness

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/08/2024 (463 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“Aaniin!”

“Boozhoo!”

It’s a breezy late-summer evening at the Forks, and a small but enthusiastic group of people are greeting each other in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) as part of a free language class led by the Winnipeg Trails Association’s Indigenous language learning team.

For three nights a week all summer (and into September), this crew has been teaching people the basics in Inininow (Cree) and Anishinaabemowin in a fun, approachable environment. On Thursdays an hour is devoted to introductory lessons in each language (Inininow at 5 p.m. followed by Anishinaabemowin at 6 p.m.), while game nights are hosted in both languages at 6 p.m. Fridays.

“It’s a completely different environment from a classroom,” says Shyla Niemi, one of the program’s language co-ordinators. “You’re not graded. It’s really laid back, We’ll laugh with you. We’re all just trying our best.”

NIC ADAM / FREE PRESS If the immersion approach at Winnipeg Trails’ Indigenous language learning program at the Forks sounds intimidating, it is — but only at first.

It’s Wednesday, which means it’s Anishinaabemowin immersion night. For one hour there is one rule: “we do not speak English” — sorry, “gaawiin giinawind zhaaganaashiimosii.”

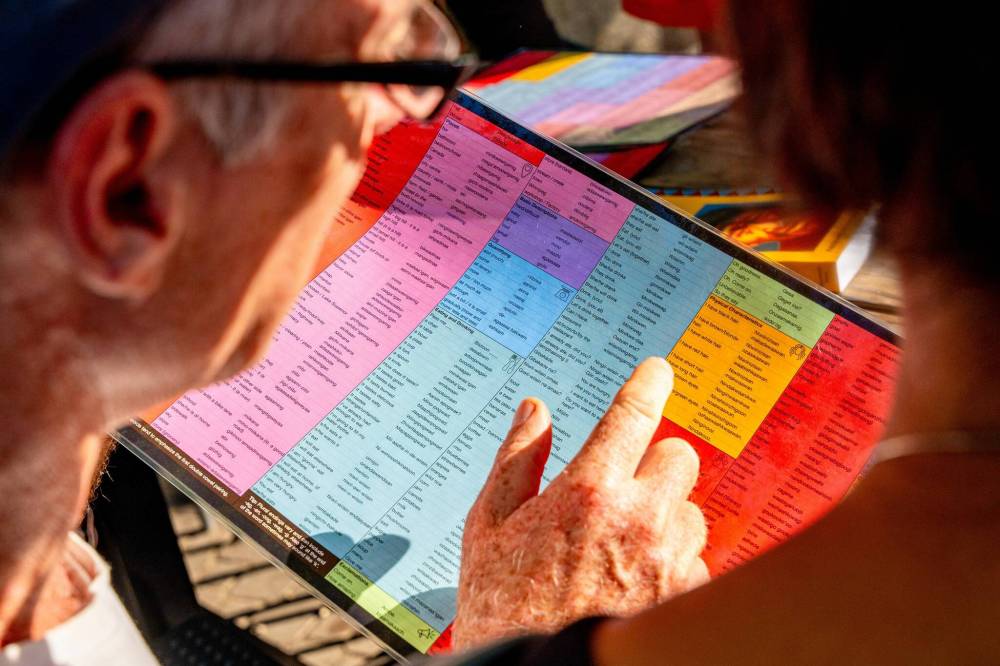

If the immersion approach sounds a little intimidating, it is — but only at first. The team — Niemi, along with fellow language co-ordinators Mackenzie Anderson-Sasnella and Justin Tuesday as well as Winnipeg Trails executive director Anders Swanson — provides participants with colour-coded placemats loaded with simple phrases, common words and conversation-starting questions, not to mention plenty of encouragement.

“Aaniin ezhinikaazoyin?” (“What is your name?”)

“Jen ndizihnikaaz.” (“My name is Jen.”)

Anyone can join a table at these open-air sessions. You can stay for the whole hour or not, though you might say “Giga-wabaamin api” (“see you next time”) or “Niin giiwe” (“I have to go home”) before you leave. Participants are encouraged to look up words and phrases and — this is key — actually say them out loud. You cannot do that thing people do in restaurants where they just point at the menu instead of attempting to say the Filipino/Japanese/French/Italian name of the dish.

“You’re not graded. It’s really laid back, We’ll laugh with you. We’re all just trying our best.”–Shyla Niemi

And there’s no rush. In the corner of each language placemat is also a pronunciation guide, which is particularly helpful for long vowels; Anishinaabemowin uses aa, ii, oo, which are pronounced “ah,” “ee” and “ooh” respectively. “Zh” is like “je” in French. Short vowels: a, i, o are pronounced “uh,” “ih” (as in “sit”) and “oh.”

You can take your time to break down each phrase.

A gust of wind temporarily takes away our placemats. Someone takes that opportunity to look up “wind” in one of the dictionaries also provided. He laughs and turns the book to the group.

There are over 100 words for wind in Anishinaabemowin.

The Winnipeg Trails Indigenous languages program launched earlier this summer and Anderson-Sasnella says it’s been a success.

“It’s only been ‘dead’ — as in less than three people — maybe two times,” she says. Sometimes the group has had to spread out over multiple tables.

Anderson-Sasnella says participants are mostly people who have no background knowledge of the languages, or just the basics.

“A lot of people are coming with, at maximum, how to introduce themselves and say thank you. Usually it’s people that are very interested in picking up a few words, or they have friends or family members who are Indigenous and they want to pay respect to or deepen that relationship,” she says.

NIC ADAM / FREE PRESS Justin Tuesday (left) and Mackenzie Anderson-Sasnella aim for a laid-back vibe where support people will laugh along with language learners.

The language co-ordinators worked with a mentor, Joyce Perrault, to create materials and resources for the program, which they also host.

They are all language learners themselves.

“I’m definitely a beginner still,” Niemi says of Anishinaabemowin. ”I’m getting pretty decent with pronunciations. I’m trying to really focus on sentence structure, which is very hard — it’s really backwards.”

She says it helps her to hear her family speak the language when she goes to visit them in Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek (Gull Bay First Nation) in Northwestern Ontario.

Tuesday, who is from Nigigoonsiminikaaning First Nation in Northwestern Ontario, grew up speaking Anishinaabemowin.

“I’ve been taking Ojibwe since kindergarten. I did kind of lose the language for a while, but as I started coming here and participating, it’s really come back a lot,” he says.

NIC ADAM / FREE PRESS On Wednesday’s immersion night, the rule is no English but language coordinator Shyla Niemi is among those offering laid-back help to Matthew Turnbull.

Anderson-Sasnella, whose family is from Little Saskatchewan First Nation in the Interlake region of Manitoba, likes encountering Indigenous languages when she’s out and about in the city.

And we’re fortunate in Winnipeg to have many opportunities to do so, whether it’s at the art gallery or at a screening for the much buzzed-about Anishinaabemowin-language version of Star Wars: A New Hope or, say, driving down Abinojii Mikanah.

Earlier this year, the City of Winnipeg officially renamed Bishop Grandin Boulevard Abinojii Mikanah, which means “Child’s Way/Road” in Anishinaabemowin. It’s a meaningful change and a significant act of reconciliation: Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin is considered an architect of Canada’s Indian Residential School system.

On social media, many people applauded the change, while others complained.

“No one is ever going to call it that” was a common refrain among the naysayers.

Some settler opposition to Indigenous place names such as Abinojii Mikanah is just racism, plain and simple.

But I also wonder if some people, and in particular settlers, are just scared to pronounce Abinojii Mikanah. Maybe they want to avoid feeling embarrassed if they get it wrong, or worry they are being disrespectful if they really botch it.

I mean, I’ve worried about these things. I remember feeling weird about saying miigwetch, or thank you. Am I even allowed to say it? I am a white lady.

But potentially feeling embarrassed about getting it wrong isn’t a good reason to avoid something. So I say … just try it. Just try saying the word. No one is going to arrest you if you mess up. Just try it, right now, out loud. Abinojii Mikanah. A-bin-oh-jee Mee-kin-ah. It’s musical. It’s beautiful. It also pretty much sounds how it looks once you get your mind around Anishinaabemowin’s double-vowel system.

Repetition leads to familiarity which leads to confidence. When Qaumajuq opened, for example, I was nervous about saying its name — Inuktitut for “it is bright, it is lit” — because I was scared to butcher it. Now, it slides off my tongue like Grosvenor or Lagimodiere.

My point is that we learn and become comfortable with regional-specific pronunciations of names and words all the time. See also: any Winnipeg Jet who has a multisyllabic last name.

NIC ADAM / FREE PRESS Christian Slomka is among students braving the challenge of Indigenous double vowels and the risk of mispronouncing new words.

And messing up is part of the process of learning. Niemi points out that even when we learn our first languages, we don’t get them perfectly right away. Listen to the way little kids talk.

“That’s a process we all have to go through,” she says.

“It’s nice to actually be able to come together with people. You’re practicing with strangers, so it’s a little less personal in a sense. They’re going through the same experience as you.”

Trying is the point, Niemi says. No one is expecting flawless Inininow or Anishinaabemowin pronunciation.

“We just want to hear it more,” she says. “And if more people try to speak it, then eventually we can hear it again, in the landscape. Like, just hear it on the bus, people talking. That’d be super cool.”

I am trying to figure out how to tell the group more about my dog Samson after answering, “Wegonen-aawi giin bami’aagaans wiinzh?” (“What is your pet’s name?”)

I am a bit too excited when I figure out he is an “animosh” (dog).

“Agaasaaa animosh?” I try. Those are the words for “small” and “dog.”

Niemi’s eyes light up. “Ah!” she says. She understands me.

Ni nanda-gikendan. I am learning.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.