Harbouring hate

Dense chronicle of the far right in Canada manages to only scratch the surface

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/02/2025 (240 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Patrik Mathews was a Canadian Armed Forces reservist living quietly in Beausejour who recruited white male Manitobans for The Base, a white supremacist group based in the U.S.

We only know about Mathews’ activities because Ryan Thorpe, then a journalist for the Free Press, risked his life to infiltrate and expose the group.

After Thorpe’s stories were published in August 2019, Mathews fled to the U.S. He was later arrested by the FBI, convicted on gun charges in a plot to kill political opponents, with his prison sentence increased to nine years to reflect his domestic terrorism.

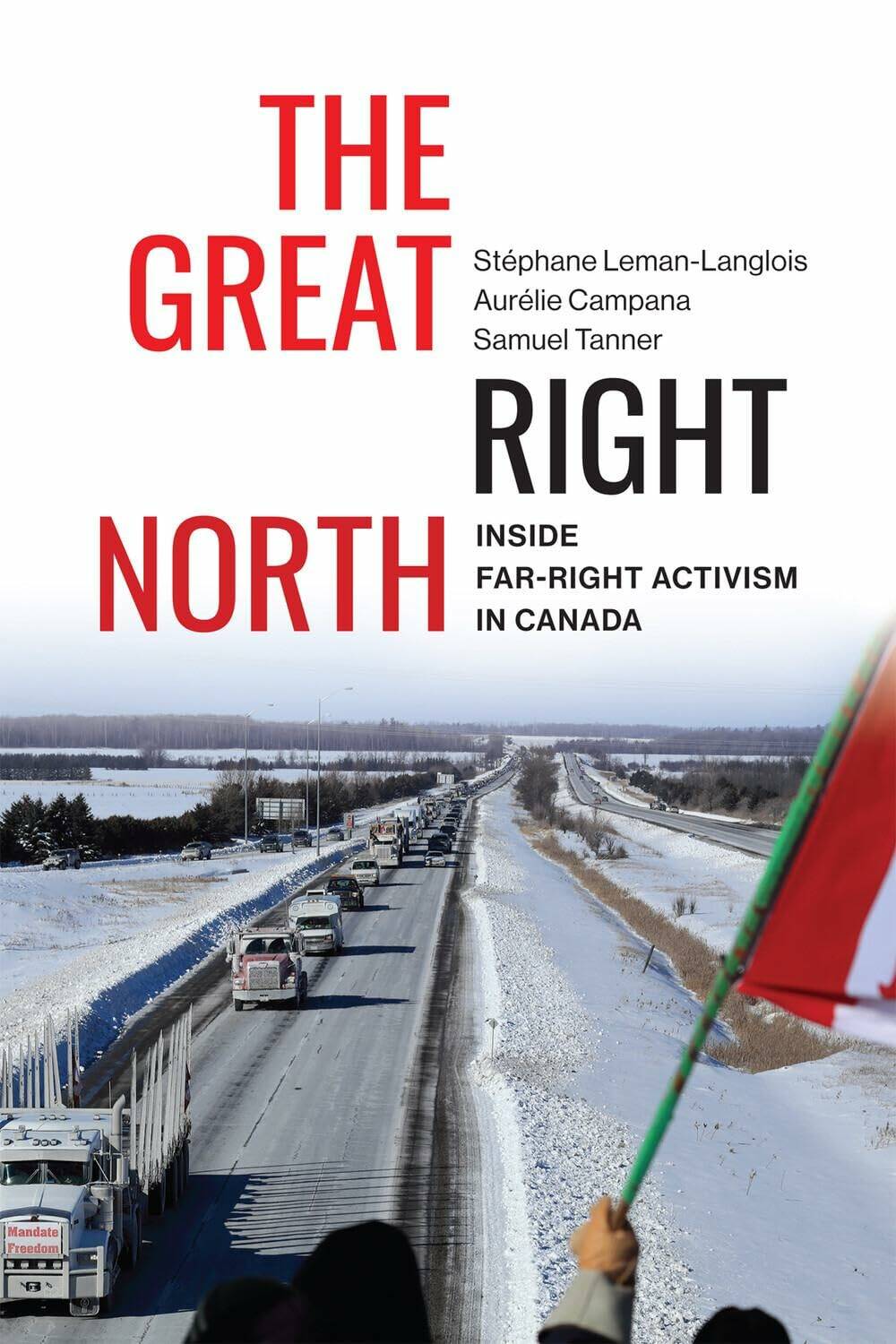

Frank Gunn / Canadian Press files

In this 2022 photo, a convoy of truckers protesting measures taken to curb the spread of COVID-19 drive to Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

The Great Right North: Inside Far-Right Activism in Canada refers to the Mathews case four times, but the authors completely mislead the reader in the way they do it. We’ll get back to that.

The Great Right North is written by academics, for academics.

Authors Stéphane Leman-Langlois and Aurélie Campana are professors at Laval University, and Samuel Tanner is a professor at the University of Montreal.

There are a few valuable contributions to our understanding of the far right in Canada in this book. But general readers have to dig hard to find them, as they are buried in academic jargon and hair-splitting.

The authors deserve credit for their analysis of a livestream by Canadian online influencer Lauren Southern from an anti-immigration protest in the Alps.

Riffing on Canadian communications guru Marshall McLuhan’s dictum that “the medium is the message,” they posit that the computer interface and social platform needed to livestream are as much a part of Southern’s message as the words she speaks.

The authors also deserve credit for conducting original research by interviewing 50 adherents of the far right — difficult and dangerous work.

They got their sources to open up. But excerpts from those interviews are used sparingly and devoid of context.

The Great Right North

One man says he stopped his far-right activity when his daughter was born. Good as far as it goes. But many questions remain. How old is he? What does he do for a living? Why did he join the far right? How did his daughter reignite his conscience?

If the authors had used their material to draw complete portraits of four or five of their interviewees, this book would have been much more revealing to non-academic Canadians.

They refer to very few specific cases of far-right activity in Canada beyond Mathews’. When they do, they still don’t provide enough detail for people who don’t already know what they are talking about.

In the Mathews case, their presentation is misleading. A paragraph near the end of the book says journalists “may be involved in doxxing,” referring to the practice of naming extremists online.

The rest of the paragraph gives credit to the Free Press and Thorpe for uncovering and naming two members of The Base in Manitoba. “All are now incarcerated,” the paragraph ends.

More than 80 pages earlier, the authors presented some of the details of Mathews’ arrest and charges. But without referring to that paragraph in this one, the authors lead the reader to erroneously conclude Mathews was locked up simply for having been identified in a newspaper as a member of the far right.

With the ascension of Donald Trump as president of the U.S., and his pardon of violent criminals who attacked the U.S. Capitol on his behalf, Canadians have witnessed what can go terribly wrong when a mainstream political party openly welcomes allies who adopt violent anti-democratic behaviour.

The authors concede that the leaking of political ideas from the far right to more mainstream parties is something “we have only briefly touched on in this book, but it is certainly worth attention.”

William J. Hennessy Jr.

In this 2020 sketch, Manitoban Patrick Mathews is shown in a Greenbelt, Md. courtroom.

Actually, they don’t touch on it at all, and it’s definitely worth attention.

They spend quite a few pages discussing the convoy that disrupted Ottawa during the COVID-19 pandemic. But they do not once mention Pierre Poilievre, the man who fancies himself Canada’s next prime minister, gleefully taking selfies with the convoy protesters, explicitly excusing them for breaking laws and welcoming their political support.

Now more than ever, Canadians need a thorough examination of how our political life is undergoing change at the hands of far-right agitators.

But this book isn’t it.

Donald Benham is a freelance writer living near Beausejour.